*The NBC-1 Report*

This article will cover the following topics:

What is an NBC-1 report, and what’s it for?

Everyone who was ever in the Army (not sure how Marines do it) remembers what the letters mean in the acronym SALUTE—

It’s a report format that permits a soldier observing enemy or noncombatant activity to organize the information he has in an orderly, easy-to-remember format, and to pass that information on in a manner that’s instantly understandable by the receiver.

An NBC-1 report is like a SALUTE report. It contains information that an observer sees and/or hears. But whereas SALUTE reports are usually about people, NBC-1 reports are about weapons; specifically, Nuclear, Biological and Chemical weapons. The information in the report helps analysts determine a number of things:

Why do I need to know it?

All well and good, gvi (you may be asking), but why would I, a civilian, need to know this?

Several reasons, the first one being your friends and neighbors. Being able to put this information up the pipeline in this format allows everyone to make the best use of what you yourself observed (wouldn’t you want to know?).

Responders at all levels need this information too. If you’re a member of an Emergency Management Agency, a CERT team member, a SKYWARN spotter, etc., the information you throw “up the pipeline” will go directly to those who need it. Being in a recognizable format, your information will be given far more credence than something like “I just saw the dangedest big BOOOM ever I did SEEEEE!”

Any disaster, especially a terrorist attack, will be immediately followed by a period of intense confusion, conflicting reports, and no small amount of panic on the part of first responders as well as the general public. A properly formatted spotter’s report has a knack of filtering itself through the dross of contradictory (and often misleading) information.

So now we know why we’d want to learn this format, and to whom we ought to send it. Let’s move on to what an NBC-1 report looks like, what goes in it, and how to find that information out.

What do I need to have beforehand?

Before we go any further, you’ll need to have certain things handy to gather your data. The good news is that these things are very simple; things you probably have with you at any given moment anyway. Some things you may not, which we’ll discuss.

They include:

What information goes in it, and how do I find it out?

As we discussed earlier, the NBC-1 report contains information about nuclear, biological or chemical weapons that an observer can see or hear.

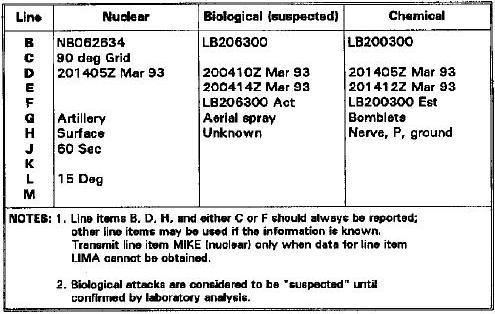

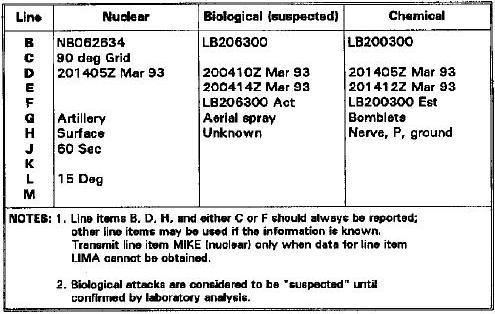

There are several NBC reports; one for initial reporting, one for follow-up contamination surveys, one for warning friendly personnel in areas for planned attacks, etc. All these reports are expressed by referring to various lines from a sort of master table that contains entries for all the types of information you could ever want to know about an NBC event. You can see a copy of the table—it’s Figure 1-5 in the FM 3-1-1, NUCLEAR CONTAMINATION AVOIDANCE.

If it looks confusing, it may be best to imagine the table as being similar to a Chinese take-out menu. For any given dinner, you order from various lines in the menu: If you want Sesame Chicken, Shrimp Fried Rice, and Crab Rangoon, you refer to the appropriate lines in the menu, and ignore the rest, since you don’t care about Kung Pow Chicken or Pot Stickers, for example.

It is the same for the NBC-1 Report. You pick out the lines from the master table (the “menu,” if you will), and ignore the lines that don’t apply. If a suspected chemical weapon goes off in your area, you don’t care about nuclear information. So you ignore it and use only the lines that apply.

From the manual linked above, here are sample NBC-1 reports:

As you can see, certain lines are used, and others are omitted. Let’s go through each line of this report and discuss it in more detail.

LINE BRAVO: Position of observer.

That’s you and where you are or were when you took the information. It’s typically expressed in UTM coordinates, and if you have a working GPS receiver handy, all you need to do is read the grid coordinates off of the gizmo. If you don’t, and if you have only a street map, as detailed a description as possible in as few words as possible (e.g., intersection of Stoney Island and 97th Streets, Chicago, Illinois). This line is important, because you will be giving direction and distance information elsewhere in the report. Analysts will need to know where you were, so they can plot the event’s location from your starting point.

Why do I mention that it’s where you were when you took the information? Simple: Once I take the information I need, I’m likely to be reporting it while moving at a high rate of speed AWAY FROM the attack! My current (and constantly changing) position is of no use to anyone in terms of this report.

LINE CHARLIE: Direction of attack from observer, to include unit of measure.

This is the compass reading FROM you TO the detonation or dispersal. When you send this line, you must specify whether you’re using degrees or mils (the other ring in a military compass, used by Field Artillery observers), and whether the direction is relative to “Grid” north—meaning you’ve used a declinated compass—or “Magnetic” north. It might sound like this: LINE CHARLIE, 070 DEGREES MAGNETIC

LINE DELTA: Date-Time group of detonation/start of attack

This line is self-explanatory, but the format may look unfamiliar. It’s nothing more than the day of the month, the 24-hour time, then the month and year, all run together. For example, the sentence you’re reading was written at 2:35pm, August 16, 2006. The DTG (Date-Time Group) would be 161435Aug06.

LINE ECHO: Illumination time (nuke)Date-Time group of end of attack(chem/bio)

Use of line ECHO appears to be discouraged for nukes; however, you may not be able to see the cloud due to inclement weather or darkness. You count (one, one-thousand two, one-thousand…) to determine the duration of the brilliant initial flash of a nuclear explosion. You mustn’t look at the flash; however, you can see the illumination begin to dim through closed eyes (face towards the sun with closed eyelids, and pass your hand in front of your eyes—that’s what you can expect to see). And since a chemical event may be a single detonation/release, meaning the end time is the same as the beginning, you are likely not to use this line. (BACKGROUND NOTE: to understand why one would want to know the “end of attack,” remember that it refers to things like artillery barrages, which can last many minutes)

LINE FOXTROT: Location of area attacked

Use this only if you know it. DON’T GUESS! Like your own position, you can use either grid coordinates or a description of the site (e.g., The old tire plant, the subway stop at LaSalle Street, the BP Refinery in Whiting, etc.). Again, DON’T GUESS IF YOU DON’T KNOW!

LINE GOLF: Suspected or observed means of attack and method of delivery

Unless you’re there when it happens, you’re unlikely to know this line—state UNKNOWN. If you are there when it happens, your ability to communicate this information is likely to be of extremely fleeting duration, and you’re probably better off saying the Lord’s Prayer or something equally appropriate in the time you have remaining. If St. Peter appears interested when you meet him, though, feel free to go ahead and tell him.

LINE HOTEL: Type of burst or type of agent

Specify airburst, surface or subsurface detonation (nuclear), or in the case of a chemical dispersal, the method of delivery (spray, bomb, airplane, etc) and the type of agent. If you don’t know, state UNKNOWN.

LINE JULIET: Flash-to-bang time, expressed in seconds.(nuclear only)

Very simply, it’s how many seconds it took for the concussion of the blast to get to you. This, combined with lines BRAVO and CHARLIE, gives analysts the information they need to accurately determine where the thing went off.

LINE KILO: Crater present or absent and diameter (nuclear)/Type terrain and vegetation (chemical)

Self-explanatory. I’m not sure what would possess someone to stick around and check out a nuclear crater. I wouldn’t. The terrain/vegetation information is useful, however, to determine where heavier-than-air chemicals may descend to, or how long the stuff may stick around on plants, buildings, etc.

LINE LIMA: Cloud width at H+5 minutes (nuclear only)

After 5 minutes, measure with your compass or other instrument, the angle between one end of the mushroom cloud and the other. This helps to determine the approximate yield of the weapon (we’ll discuss how to determine yield in another article).

How to measure the angle of the cloud width. You may not be able to see opposite edges of the cloud (you can visualize what I mean if you put your eye close to a coffee can—you’ll observe that you can only see about a quarter of the way ‘round it). That’s okay, just record the angles to the edges you can see. Analysts who take your information will understand this, and will plot your angles and distances in such a way that the cloud will come out the right size.

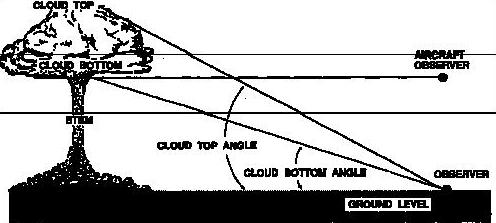

LINE MIKE: Stabilized cloud top or cloud bottom angle or cloud top or bottom height at H=10 minutes (nuclear only)

This line takes some explaining and maybe a picture or two.

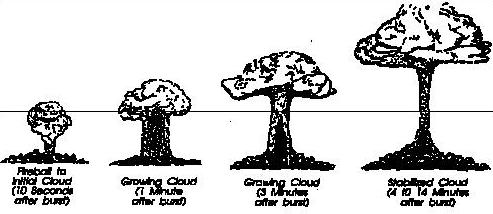

After about ten minutes, a nuclear cloud will stabilize, and begin to be affected by prevailing weather patterns more than by its own energy. It will rise until it hits a stabilizing layer of air, tops out and begins to disperse (imagine the “anvil head” of a thunderstorm—same difference). The mushroom cloud will not rise past this point, but rather will spread out and be borne by the wind. Analysts use this information the same way as they do with line LIMA—estimating the size of the weapon.

Nuclear cloud development. A nuclear cloud will begin to be influenced by the weather after about 10 minutes, give or take. The size of the cloud JUST AS this happens can help analysts determine the size of the weapon.

The picture below shows how to measure the cloud height.

Make sure you specify whether you’re measuring to the cloud top or bottom.

NOTE: Refer to the table above, and you’ll see that it’s only used when you can’t determine line Lima (as for example on an overcast day).

How do I submit it? To whom?

Let’s answer the second part first.

At the risk of alienating the “Blue Helmet and Black Helicopter” set, I submit that the first people that need to know the information in this report is the authorities.

That’s right—you heard it here first, folks. A honest-to-goodness survival article written by a real-live survivalist telling you to go and give information to “Them.”

Before you brand me with the stamp of heresy, indulge me for a minute. If you’re anything like me, you don’t have a Nuclear Emergency Search Team working for you. If you’re anything like me, you don’t have your community’s emergency services on your payroll. And if you’re anything like me at all, no newspaper or television reporter is going to come straight to your office fifteen seconds after the Bomb went off, hounding you with questions about your slow and inefficient response.

No, if you’re anything like me at all, your needs are immediate and localized—secure your safety and that of your family, and come to a decision whether to evacuate or shelter-in-place.

But suppose Fate places you in a position where you can safely take this information down. Isn’t being able to do so and keeping that data to yourself a little bit like seeing an electrical fire start in your hotel room and leaving without even pulling the fire alarm?

Say whatever else you want about our nation’s governments, it must be admitted that responding to an NBC weapon falls within their purview for better or for worse. Given what we know about their responses to disasters with little or no useful information (or worse yet, conflicting information), it’s easy to see that one’s own self-interests are served by making sure they have accurate, reliable data.

You can send the data over phone, voice radio, data radio, or whatever means works. It pays to know ahead of time whom you will send this kind of information to. For example, I have an out-of-state friend whom I’d send the report to, ham radio friends involved in the County EMA, a member of my Army Reserve chain-of-command, etc. Have these relationships in place before you need them, since “Joe Stranger’s” report will bear less credence than “Joe-whom-I’ve-known-and-worked-with-for-two-years’s” report saying the same exact thing.

As far as sending the report, it’s relatively straightforward. Make contact (by whatever means) to the party who is to receive/relay the information. If that party is or was military, it’s easy, “YOU THIS IS ME NBC-1 FOLLOWS, ACKNOWLEDGE, PLEASE.” Trying to make civilians understand this is different. May I suggest the following: After you establish what you’ve just seen with the other party, say, “I HAVE AN OBSERVER’S REPORT IN STANDARD GOVERNMENT FORMAT. PLEASE WRITE DOWN EXACTLY WHAT I SAY, AND REPEAT IT BACK TO ME LINE BY LINE. DO YOU UNDERSTAND?”

After you get acknowledgement, send the report line by line, eg;

LINE BRAVO, NOVEMBER BRAVO ZERO SIX TWO SIX THREE FOUR OVER

(pause and have the line repeated—make sure to correct any errors)

LINE CHARLIE, NINETY DEGREES GRID OVER

(pause)

LINE DELTA...

...and so on.

Make sure the person taking this down, whether Rubie, EMA personnel or military, repeats the information back to you, so you can correct any mistakes.

How can I practice putting this report together?

But gvi, I’ll never be able to practice this! How am I going to know how to do this when the time comes?

A fair question. Atomic detonations and chemical plumes don’t grow on trees (thank God!), so there’s sort of a shortage of things to go out and practice on.

Or is there?

I’m willing to lay fairly good odds that you’ve got one of these somewhere near you:

They bear a passing resemblance to the object of our inquiry, don’t they?

Using these, a training program is quite simple really. Just go out to the nearest water tower, with compass, map, GPS, and worksheet in hand. Take a few measurements, and fill the form with whatever information you take down. Here’s an example of a form I filled out, using my town’s largest water tower as a training aid (Photo 1 above):

| BRAVO - your location | DL 9262 9163 (Sturdy Rd 150 ft N of Grand Trunk RR tracks, Valparaiso, IN) |

| CHARLIE - direction to attack | 91 Degrees Magnetic |

| DELTA - DTG, start of attack | 072231SEP06 |

| ECHO - Illum (sec)/DTG, end of attack | |

| FOXTROT - location of attack | |

| GOLF - means of delivery, kind of attack | |

| HOTEL - type burst/type agent | Surface |

| JULIET - flash-to-bang (nuke only) | 1.5 sec |

| LIMA - cloud width H-5/terrain & veg | 1.8 degrees |

| MIKE - cloud height H+10 (nuke only) | |

| NOTE: Use line MIKE only if you can't get line LIMA |

NOTE1: I used a rangefinder to measure the distance from myself to the water tower (Picture 1 above), then used the speed of sound (350m/sec) to convert that distance backwards into “flash-to-bang” time for line JULIET. If you can determine a good distance when you practice, you may want to do this. It’ll give you something to work with in the next article.

NOTE 2: The time stamp on the photo is when it was uploaded to my computer—the photo was actually taken around 7:15pm. But since the time stamp is on the photo, I used it to give an example of where the DTG comes from and what it looks like.

Of what use is this information to anyone?

As we learned earlier, the information a careful observer gathers can help Emergency Responders understand the magnitude of the event, predict the areas that will be affected, to what degree an area will be affected, determine bug-out routes, warn others, and so forth.

Analyzing the data can be found in an article on the Rubicon side, but for now, there are tools available in the Public space that can help us evaluate data from NBC attacks. The Nuclear Fallout Predictor (available here) can give a rough idea of how greatly any downwind area will be affected by an atomic detonation occurring upwind. There are other factors to be taken into account, of course—local weather patterns, shelter construction, exposure time, and so on—but the Predictor is a fair starting point.

Chemical weapons are affected by the same exact phenomena that affect smoke from a campfire—wind, humidity, the composition of the material released, and so on.

Some additional thoughts

The first consideration in any NBC event is one’s own safety. Robert Heinlein wrote that the best way to survive an atomic bomb is to not be there when it goes off. The trouble is that we don’t know when a bad guy might detonate an atomic weapon or disperse chemicals—our only warning may be the dazzling initial flash of the fireball or observing the effects of a chemical attack on yourself or others. Your own safety is paramount and of course common sense.

The report format we’ve discussed was designed around likely battlefield uses of NBC weapons; that is, munitions delivered by air, missile, artillery or land mine. While none of these are outside the realm of possibility, it’s unlikely that we, as civilian survivalists, will encounter chemical or biological artillery barrages or gas mines. Take that into consideration.

One can always hope that being in the vicinity of a domestic NBC attack will happen to the “other guy.” And unless you live in a major urban area, this is likely to be the case—99% of America will only learn about an NBC attack from television or radio news. But if Fate places one or more of us within observation of a nuclear or chemical attack, we owe it to our fellow friends and neighbors, when consistent with personal safety, to report the information we see and hear.

APPENDIX

NBC-1 Report Worksheet (as an Excel spreadsheet):

Print this sheet out and keep it handy with the other items discussed above. You can laminate it and write on it with a grease pencil; not that you’ll have that many real-world NBC-1 reports to submit (if you ask me, one’s too many) but it will stay together better for training, and be there when you need it. A short description of the line item is included with each, but it may be wise to print out the whole article so you’ll know what kind of data to send. After all, I’ve done these things a few times, but I doubt I’d be in command of both my memory and my presence of mind should I need to send a real-world report.

GVI

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2007 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.