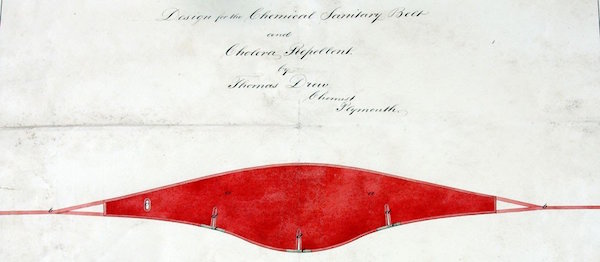

"Design of the Chemical Sanitary Belt and Cholera Repellent by Thomas Drew, Chemist, Plymouth."

*"Cholera Belts"*

"Design of the Chemical Sanitary Belt and Cholera Repellent by Thomas Drew, Chemist, Plymouth."

One of the things that sets "progressive" reenactors apart from "mainstream" ones is their desire to be "period correct" in places no one but their spouses or undertakers have any business looking. This includes undergarments, whose history is simultaneously well-researched among costuming experts and relatively unknown to the wider world. I've written before about Portyanki and Fusslappen, and the research for that article left me knowing far more than I ever wanted to learn about German and Russian soldiers' feet - ugh! In like manner, the research for this article obliged me to learn about some of the more misguided theories of Western medicine; and now you get to learn about them too.

This article is only going to dwell on one garment which seems to have existed across many cultures at more-or-less the same time, though there was little attempt at "cross-pollination" or sharing of ideas regarding it, one culture or nation to the next. It went by many names but for brevity's sake I'll use a catch-all term "belly-band."

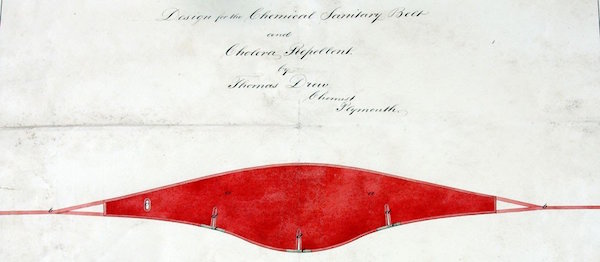

These were either knitted tubes or lengths of cloth of various types - often wool flannel - worn around the midriff under everything else. Some of the non-tube ones looked like a sash and some looked like a modern cummerbund worn backward; i.e., with the wide part at the back. Most had the object of heat-retention in mind, but many had other purposes. The Japanese senninbari haramaki ("thousand-stitch belt"), for example, was intended to bring good fortune to the wearer.

A well-preserved example of the senninbari or "thousand stitch belt" most Japanese soldiers were given while away on active service.

The process of making a "thousand-stitch belt" involved family members hanging out in public places like train stations and markets, asking passers-by to make a few stitches on behalf of the soldier to whom it is to be sent. Say whatever you please about the beastliness of the Imperial Japanese Army in WWII, I find this "home-front" practice quite touching and admirable.

If what I saw online while looking things up for this article is any indication, women's fashion produces a variety of close-knit, form-fitting tube-type garments whose function is not merely warmth, but also to cover up the space left bare by the cut of women's pants and tops. I'll leave it to others to tell me how common they are and how good a job they do, though I will say I think it's sensible - if designers can't be bothered to provide women with cold-weather clothing that's attractive, comfortable and practical, expedients like belly-bands are unavoidable.

The practical nature of these undergarments appears to be based on the idea that keeping the lower abdomen warm keeps the rest of the body warm. There's a measure of superficial sense to this - belly-bands tend to wrap around the kidneys, through which blood constantly flows as they do their job of filtration. The kidneys are near the surface of the skin, so heat loss in this area may have a disproportionate effect on the body's ability to regulate its own temperature. I am not certain of the science on this, and I have no doubt someone's going to come along and set me straight.

Whatever. This is what many of our ancestors thought the belly-band did; and right-or-wrong, this is why they wore the things. I'll discuss my own experience with a modern version presently.

What makes these undergarments interesting to me is how they reflect the thinking of the period, both in practical utility and in misguided theory. I'll explain what I mean but for a hint, we can look to their names in different languages.

Note this last entry. The British called their garment a "cholera belt" and they had been in use by that nation from the 1700s until the early part of the 20th century. I have in my digital library a 15-page article written by an E.T. Renbourn entitled The History of the Flannel Binder and the Cholera Belt which tells the reader much more than anyone would ever care to know about the things.

They were so named because of the mistaken theory that cholera was caused (or the symptoms of it worsened) not by bacteria, but by loss of "vital warmth." It should be remembered that while "animacules" were discovered in water with Leeuwenhoek's first primitive microscopes in the mid-17th century, their connection to human disease was unknown or unproven until much later. Withal, the name and the idea stuck with the English garment until its abandonment in the mid-20th century. According to the article cited above (which you can find online if you don't want to follow my link), some of the victims recovered from the sinking of the RMS Titanic were found, upon examination, to be wearing cholera belts.

It was supposed that red flannel was superior to that of other colors for preventing cholera. Your guess is as good as mine as to why.

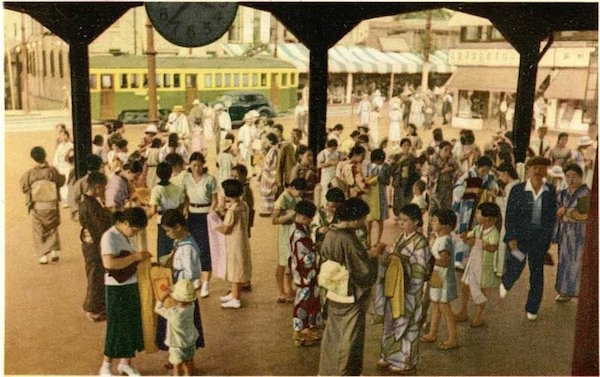

Cholera belts at the turn-of-the-last-century were manufactured by the same firms that made hernia trusses and other supportive garments.

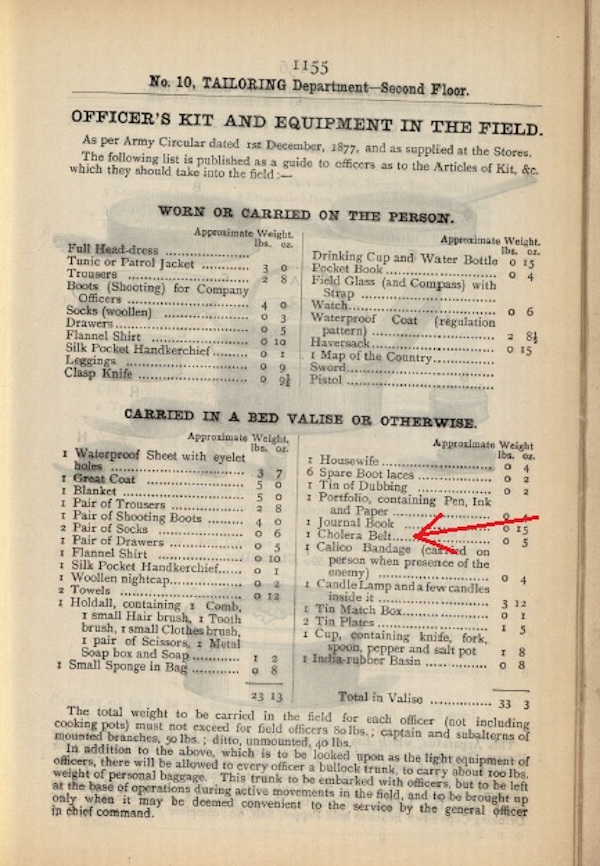

From the 1883 edition of the British "Army & Navy Co-Operative Society" catalogue.

"The A&N" was a sort of cross between the Post Exchange and the Sears Roebuck & Co. catalogue, primarily for Officers, Senior NCOs and

Civilian administrative officials in government service overseas. Their catalogue contains EVERYTHING for exploring the Empire, and

for "civilizing" it after you'd finished mapping it out and subduing the original inhabitants.

As a preventive for cholera, the things of course didn't work and couldn't possibly have done. What's more, some British physicians in the past suggested wearing them even in the hottest part of the year ("cholera season" was historically May-through-July in India), which doubtless contributed to heat injuries at a greater rate than had this advice not been followed.

"Mad dogs and Englishmen" indeed!

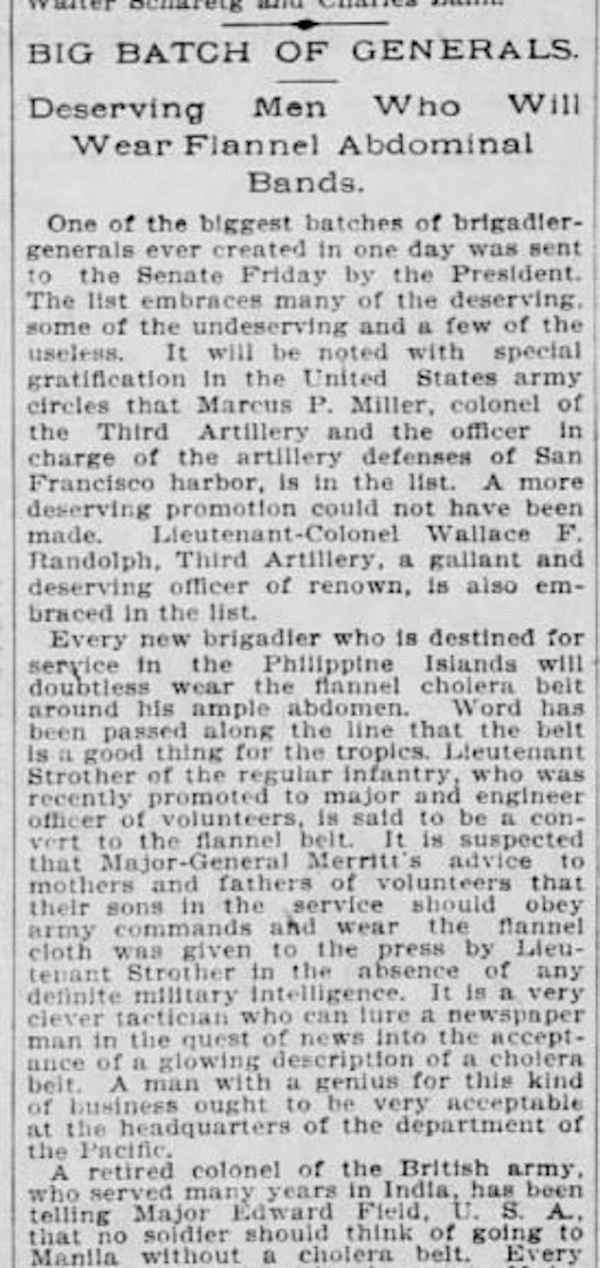

The article linked above notes that medical experts in the United States either recommended against their use or were at best indifferent. If you look up "cholera belt" in Wikipedia, you'll discover, near the bottom of the entry, a link to a sharp-tongued newspaper clipping from the San Francisco Call (May 1898) related to the American occupation of the Philippines. It discusses, among other things, a British medical officer's adamant advice on the cholera belt, and it does so in a clearly dismissive and derisive tone. The Wikipedia entry is unintentionally funny inasmuch as the obvious sarcasm on the part of the journalist has altogether escaped the notice of the entry's author.

Those of you who think journalism of the past was more polite & refined than nowadays are profoundly mistaken.

Americans did not and do not consider themselves in need of advice from foreigners in enduring hot, tropical climates; after all, we have our own.

While the uselessness of the "cholera belt" as a medical preventive is and was known for some time in the United States, it may be guessed, given the immigrant nature of our Nation, that at least some newly-arrived populations made use of some sort of knitted or woven belly-band, likely in the colder regions and among populations accustomed to harsh winters. I do not know whether Canadians adopted the garment - largely because I can't be bothered to look.

German example, called a "Liebbinde" or (less charitably) a Lausgurdel (which means exactly what it sounds like).

I do not know whether the Germans thought it had anything to do with disease, or was simply a cold-weather garment.

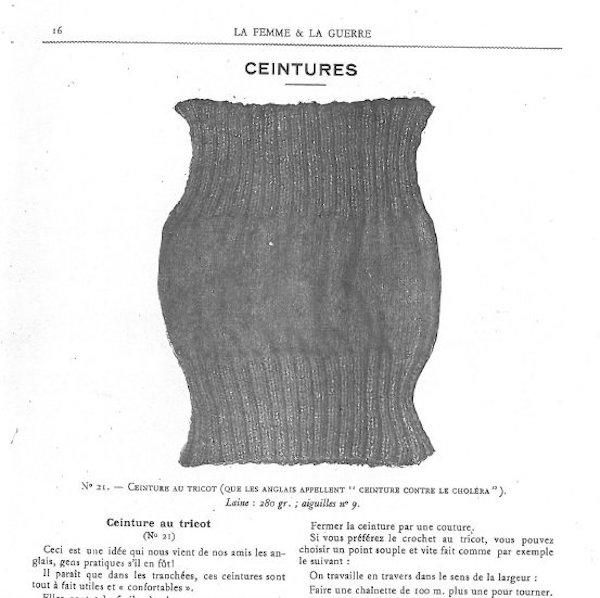

From a booklet of knitted items for French women to make for their men in the army in WWI, complete with instructions.

France wasn't the only nation whose women were encouraged to make up the difference between what was issued and what was needed.

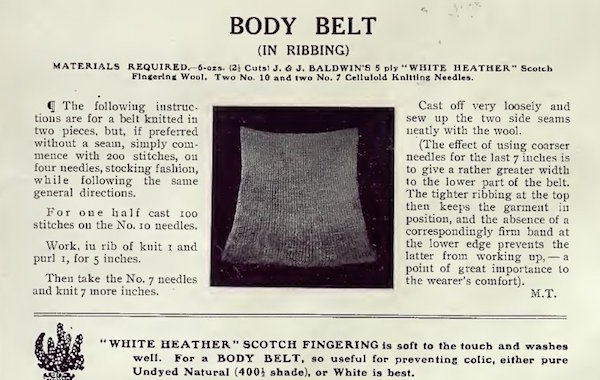

This example came from a similar source to the previous one - a booklet of items to make and ship to British soldiers in France & Belgium.

As a cold-weather garment, there's a deal of sense to it. As a disease preventive, it's of no use whatever.

And it is precisely here that we leave the world of quackery and enter the realm of plausible practicality. The "belly band" of Western civilization - by whatever name it may be known and in whatever form it takes - has always had as its object the retention of bodily heat.

I can report the following based on first-hand personal experience. I am a land surveyor by profession. Previously, I'd spent a great deal more time "in the field" than now, and naturally a fair portion of this was in winter. I should also add by way of background that I suffer from frostbite in my hands, which adversely affects my ability to work in cold, and I've become quite creative in chasing after a practical way to keep my hands from painfully "shutting down" when the mercury drops.

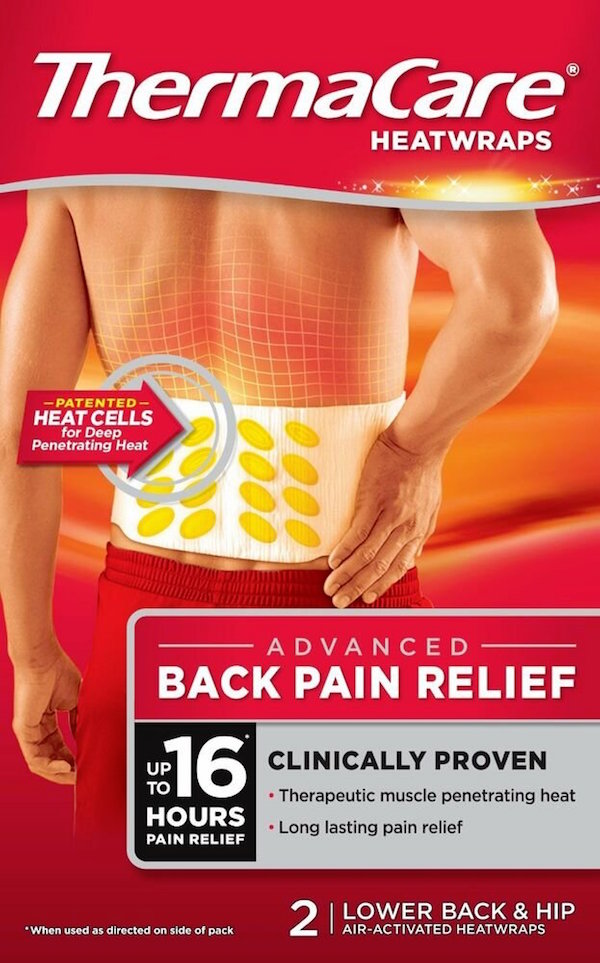

One of these techniques was a modern wrinkle on the belly-band. In American drugstores, you used to be able to purchase a simple belt that looks like a cummerbund in reverse, made of something that looks like fibrous, porous paper and Velcro tapes. This cummerbund had two pockets, into which go a disposable "Heat Pack" envelope. These items are sold primarily for sufferers of lower back pain, and I've used them for temporary relief of kidney stone pain. In this last regard, they don't work nearly as well as sitting in a tub of extremely hot water, but you can't take a tub of extremely hot water with you wherever you go. So for pain at the level of kidney stones, the heat-pad is "better than nothing."

Modern example. Mine was only slightly different.

Since I had some of the heat-pouches left, as well as the pressed-paper belt, I tried it as a means of keeping warm while out in the field. I am pleased to report that I was generally warm throughout - much more so than had I not worn it - and more importantly, my hands required much less attention than they would have needed otherwise, by virtue of a sure supply of warm blood flowing to them and keeping the tiny vessels in the fingers from contracting. I had to be judicious in my choice of clothing, because in order for the heat pouches to work they must be exposed to fresh air, which meant I had to keep my clothing more loose-and-untucked than normal. But it was worth it - the things work, and the principle of introducing heat into the body in such a way is sound, even if the idea of staving off bacterial infection is quackery.

Nowadays these belts are so made that the heating element and the belt is all one disposable unit. But you can buy heating pads of the type that came with the older belt, and I think this is superior, since the heating pads can be used other than simply the back. I have a quantity, and made a "cholera belt" out of leftover cotton material to receive the heat pads.

Made on a 1916-vintage treadle sewing machine, and I'm no tailor.

This, then, is an improvement on the "cholera belt" or "belly-band" generally. They all work to retain the body's natural heat. But the thing I made (and which you can either buy ready-made or make yourself - it's pretty simple) has the advantage of introducing heat into the body; moreover, introducing it into a portion of the body that is most able to receive and distribute this heat. It is best for low-intensity activities like still hunting, operating snowmobiles/komatiks/etc., standing relatively motionless behind a surveying instrument for hours at a stretch and so on. Vigorous activity encourages the body to produce its own heat. It also recommends itself for sufferers of mild hypothermia.

We live in an age of marvels and wonders - most of which we take for granted, and many of which we don't understand or aren't even aware of. Humanity accepts scientific progress with a faith previously accorded to religion; in fact, science has become an ersatz religion in many quarters - much to the dismay of working scientists!

But it wasn't always so. In the Victorian Era, many theories ended up running into scientific "blind alleys" or dead-ends. "Luminiferous Aether" and "Phlogistons" come instantly to mind. Medicine was equally full of mistaken ideas - the first Merck Manual published in 1899 has many notions of diagnosis and treatment that are simply breathtaking in their uselessness or danger; however, we must remember they were based on the best knowledge available at the time, and were undertaken in good faith attempts to relieve suffering. And we ought also to remember that "medicine shows" and the associated "patent quackery" in the 1800s were not merely staples of Wild West fiction. People believed in - and paid for - a great deal of hogwash back then, much like today.

It is reasonable to suppose, therefore, that our "post-abundance world," (if we want to use a nicer term than 'TSHTF') will quickly fill with an equal amount of misguided scientific beliefs in the absence of reliable authority. We all saw it ourselves just a few short years ago. A great place to start in learning about "things we now know to be balderdash" is the Wikipedia entry entitled "Superseded Theories in Science."

The "cholera belt" is balderdash. The belly-band for insulation and introducing warmth is not balderdash.

GVI

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2024 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.