*"Iron Rations" From Around The World*

By: gvi

28 April 2019

Every so often I get the itch to look up old recipes. Unfortunately, I'm also fundamentally lazy, so the recipes tend to be plain, simple "peasant food." This last round of looking up old concoctions turned to things soldiers from other countries would cook in their mess kits. Additionally, I spent some time and effort finding some of the foods that made up other countries' "Iron rations" - those things a soldier kept with him and didn't eat unless there was no way to get freshly-cooked rations up to him.

This essay revolves around "rations" as commonly understood: those foods which a nation will provide to its soldiers as part of its own planning and expense. It will not discuss what folks sent from home, the "pogie bait" soldiers would buy off sutlers, grog-sellers and camp followers, or captured enemy stockpiles. We also won't spend much time on the rations they had in garrison or in "static" positions like trenches, forts, outposts and the like, and only briefly glance at what their field kitchens and bakeries were up to.

The reader is encouraged to learn about these topics, and a few "additional information" links will be provided at the end of this essay. Meantime, the remainder is composed of the foods I've tried similar to "iron rations" or "marching rations" which I find appealing, as well as a discussion of the rations of the nations themselves at the time they were in wide use.

Introduction - What I Find Interesting About Soldiers' Rations

Before the middle of the 19th century - the 1853 Crimean War is as good a starting point as any - the rations provided to a soldier in any given army were, accounting for national tastes, practically indistinguishable from those of any other. During the Crimean War, we begin to see certain nations take increased interest in the fare offered their armies, while remaining within the bounds of military necessities. There are many reasons this change begins when it does. The first is Alexis Soyer, who completely changed the way the British Army fed its soldiers. His biography is worth reading - see the link at the bottom. Next, from time immemorial the diet for the average soldier was only better than that of a civilian of equal station in terms of reliability, not quality. Once the benefits of the Industrial Revolution (as well as those of colonialism) began devolving down to European society after 1850 or so, the quality, variety and security of everyone's diet improved accordingly.

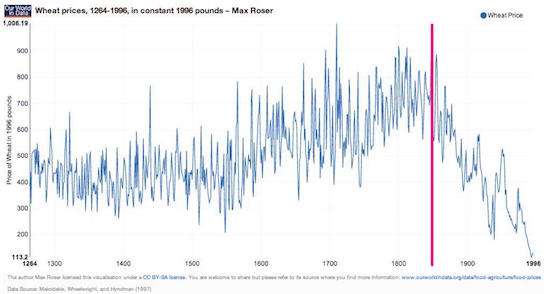

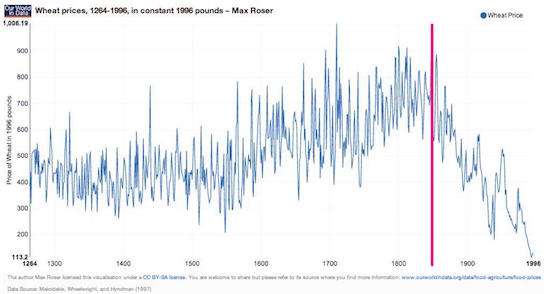

The red line, marking the year 1850 +/-, shows how food prices (the price of wheat is a reliable index) began a steady decline for the next 140 years.

It indicates that prosperity and modernity had the biggest impact on the quality of soldiers' rations.

It's easy to infer too much from a study of the various nations and their rations - 19th century economics play the largest role in what a given nation's soldiers ate. Still, a certain correlation appears between the degree of "progress" (not always the same as "improvement") a nation makes in regard to its rations, and the degree of concern that nation has as a matter of doctrine in the individual soldier himself. Put more simply, if a nation considers its soldiers cannon fodder, it tends to take little interest in what they're fed.

To demonstrate the distinction, we can compare the diet of the American GI serving in the Pacific theater in World War II, versus his Japanese opponent. The American was supported by everything from months of stateside training to entire industries devoted to his morale and welfare, and he was very well fed for the times: from A and B rations (standard perishables, or the same adapted to field kitchens), the overutilized C and K boxed/canned rations, various "emergency" rations and others, each with a considerable amount of dietary research - good or poor - backing them up. For his part, the Japanese soldier was told that his value to the war effort was worth exactly the two-cent stamp necessary to mail the form for his replacement. His subsistence in the field relied mostly on a reliable but monotonous diet of rice, barley and fish, with a bit of green tea when he could get it. This he was expected to supplement with foraged vegetables, sundries from home and - let's be honest - pillage.

We could try to make the same comparison between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army, but it's harder because of the nature of their brutal conflict. Before Operation Barbarossa, the two armies - not yet enemies - were just about similar in terms of their soldiers' rations, though the Germans' varied fare would still have been lavish to a Russian soldier. This all changed once the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, and it's no surprise the Red Army's diet was poor from that moment on. By the end of the war, however, the Russian - now far better trained and led than his German opponent - could count not only on regular issue of his normally simple diet, but also things like Spam and "bully beef" (canned corned beef) from his allies, as well as a few tinned items from his own nation's recovering industry.

You can read all about this and many other military food-related topics at the links at the end. For the truly interested reader, I'd also recommend a study of home-front cooking as well, something I'm not nearly as well informed on as I should be. The two World Wars forced the belligerents to change their habits and tastes, and as we will see, several of these changes are still around today.

Now then, on to the chow...

Buckwheat with Mushrooms - Memento Mori

Buckwheat, prepared as a sort of porridge, is known in Russia as "kasha," and until Russia finally got around to providing pre-packaged meals, kasha was one of the few things a Russian soldier could rely on receiving with any regularity.

The names for Russian food, particularly its staples, tend to fall into two categories. They either sound like charming terms of endearment elders might give their grandchildren (as with "kasha" above), or else they sound like names 17th century apothecaries might give to festering sores. For example, the Russian word for "bread" is "khleb," and "sprot" is a sort of herring. Russian is funny like that, and whether a food's name dances into our ears or just sort of contaminates them has little relation to its taste.

Posts in recipe blogs all follow a certain convention. Any recipe worth sharing has to have its own charming story, in addition to what you need to know to make it. There's also a tendency to oversell a given food. So it is with the "buckwheat with mushrooms" which I found at the blog linked below. This recipe is worth following as-is. While it's quite good, it's not as good as "Natasha" (the blog's author) makes it out to be. And since I only skimmed the "charming story" about "kasha," I don't know if it's what "Natasha's" grandmother used to call her. It's up to you whether you want to find out or just scroll down to the recipe like I did.

https://natashaskitchen.com/buckwheat-with-mushrooms-3-giveaways/

Kasha is kind of what rice would be like if rice had personality; specifically the personality of your great-aunt who spends way too much time in church, but at least she puts cold hard cash in your birthday cards alongside the newspaper clippings about starving orphans in Whateverstan, to whose relief she expects you to donate her gift. It's good food to contemplate your sins to, and likely pairs well with distilled spirits which, alas, I took The Pledge on back during the first Bush administration.

Again, I hasten to remind the reader it really tastes not bad at all, but it has a character to it which is wholly absent in foods developed in the 20th century. Any food contrived after about 1919 is intended above all else to be as yummy as art and science can make it; nutrition is either assumed or dispensed with entirely.

"Buckwheat with Mushrooms" is nothing like that. You really are reminded when you eat it that you have ancestors whom you can actually name and identify in photos, who lived through diphtheria, Cossack raids and ship sinkings; and you understand why faith in the Hereafter was until recently such an absolute and immediate necessity. It's not often you run across a food which communicates mortality so unambiguously - the fact that however much we enjoy eating, the reason we do so is in order that we shall not perish.

Buckwheat with Mushrooms is the most Calvinist recipe ever invented.

The recipe says it serves four. Unlike most recipes' portion sizes, "Natasha" gets this one right. You don't go through very much before you start worrying about your colon and simultaneously picturing the "Baker" shot of Operation Crossroads.

Buckwheat groats (was ever a food less appealingly named?) are the filler in kiszka, which happens to be my favorite breakfast sausage. So they've got that going for them. As I only made this dish without any other food - having no idea what on earth would properly accompany it - in future I'll have it with kielbasa and a spicy brown mustard, with maybe beets or something similarly acidic.

BOTTOM LINE: It should not be thought of as a stand-alone meal. You really need something to go with it, though it needn't be fancy. As a "marching ration," it passes, being easy to prepare, amenable to "doctoring up" and very filling.

Boribap - Korean Mess-Kit Chow

This is nothing more than plain white rice with barley, some butter, sesame oil and chives.

https://www.foodandwine.com/recipes/barley-and-rice-with-sesame-oil-and-chives

I got inspired to look for something like this after reading what the Imperial Japanese Army used to feed its troops. Their daily staple looked a lot like this, with fish or some other meat thrown in apparently as an afterthought.

Japan was somewhat unique among the armies in World War II in that they never adopted a unified mess system for troops in active combat (all armies eat from a central mess when in garrison). Most armies had some sort of field kitchen system, which worked either extremely well or not at all, depending on the fortunes of war. Imperial Japan, however, expected her troops to do their own cooking. This had the effect of making their logistics somewhat easier and making sure that their soldiers didn't starve when separated from the Regimental "trains," but it also meant their diet was more-than-ordinarily monotonous. And as the war turned progressively against Japan, her soldiers did frequently starve.

When I did a search for "rice and barley recipe," the linked one came up and I was pleased to find it was a Korean regional variation. Just on general principle I like the Koreans a lot better than the Japanese anyway.

While the recipe in the link above will work as its authors describe it, I adapted mine to be more "field friendly."

- I used "quick" barley; and I recommend this substitution because, while it's more expensive per pound than the bulk kind, it has the advantage of being able to be cooked simultaneously - and at the same proportion of water-to-grain - as the rice.

- Likewise, I used the cheap dried chives from the Walmart spice section. The recipe calls for a cup of fresh stuff - use no more than a couple tablespoons of the dried herbs! This goes for all spices and herbs generally - when a recipe calls for fresh herbs, use one quarter the amount of dried.

- For this recipe, cut back a bit on the butter and add a bit more sesame oil or the result will be far too "heavy." The oil gives a much better taste, and butter makes it nice and smooth, but in truth any oil and fat may be used - the bacon fat from breakfast, for example. You could also substitute green onions instead of chives without ill effect.

These two grains mixed together are the same sort of staple as the buckwheat above, but the addition of the chives makes it a much "friendlier" taste, in the sense that - for me, anyway - eating it doesn't inspire memories of immigrant ancestors, Eastern Orthodox funerals and "The Hun." That said, I had no difficulty imagining myself eating it out of a mess kit with a burning Type 97 Chi-Ha tank in the background.

BOTTOM LINE: Tasty, filling, simple. Have something sweet or spicy to complement it. Kippered herring in mustard sauce (or an equivalent) would be an agreeable trail-side meat portion. Definitely serve white wine instead of red or beer, if you must have alcohol with it.

Erbswurst - "Dynamite Soup"

"Keep away from children -

Use Only Under Adult Supervision"

Campbell's soup can for scale

Erbswurst - literally "pea sausage" - is a cylinder of compressed pea soup with a bit of bacon fat mixed in and made imperishable. Sadly, the Knorr company discontinued making it three or four years ago, but there are recipes to make one's own, if you want to take the trouble.

https://www.meatsandsausages.com/sausages-by-country/german-sausages/erbswurst

Erbswurst really was an "emergency ration," one of the first ever created by a European nation. It was used from the 1870 Franco-Prussian War up through World War I. The German Army stopped issuing Erbswurst to its soldiers, but in World War II instead issued something extremely similar in their "cold rations" in the form of a block of compressed split-pea and dehydrated vegetable soup called, unimaginatively, "Erbsensuppe."

Horace Kephart discussed it at considerable length in his 1918 magnum-opus "Camping and Woodcraft" (perhaps the best book ever written on the subject - 100 years old and still relevant) and I take the liberty of reprinting here what he had to say, as he says everything I could, only much better than I can:

In 1870 there was issued to every German soldier a queer, yellow, sausage-shaped contrivance that held within its paper wrapper what looked and felt like a short stick of dynamite. No, it was not a bomb nor a hand grenade. It was just a pound of compressed dry pea soup. This was guaranteed to support a man's strength for one day without any other aliment whatever. The soldier was ordered to keep this roll of soup about him at all times, and never to use it until there was no other food to be had [NOTE - most iron rations the world over were only to be eaten upon the order of an officer, and many were labeled to this effect]. The official name of the thing was erbswurst (pronounced airbs-voorst) which means pea sausage. Within a few months it became famous as the 'iron ration' of the Germans in the Franco-Prussian war...

Erbswurst is composed of pea meal mixed with a very little fat pork and some salt, so treated as to prevent decay, desiccated and compressed into rolls of various sizes. It is much the same thing as baked beans would be if they were dried and powdered, except that it tastes different and it contains much less fat. I understand that the original erbswurst, as prepared by its inventor, Grunberg, included a goodly proportion of fat; but the article of commerce that appeared later had so little of this valuable component (by analysis only 3.08%) that you could scarce detect it.

Nobody can spoil erbswurst in the cooking, unless he goes away and lets it burn. All you have to do is to start a quart of water boiling, tear off the cover from a quarter-pound roll of this ''dynamite soup," crumble the stuff finely into the water with your fingers, and boil for fifteen or twenty minutes, stirring a few times to avoid lumps. Then let the mess cool, and go to it. You may make it thin as a soup or thick as a porridge, or fry it after mixing with a little water, granting you have grease to fry with.

It never spoils, never gets any 'punkier' than it was at the beginning. The stick of erbswurst that you left undetected last year in the seventh pocket of your hunting coat will be just as good when you discover it again this year. Mice won't gnaw it; bugs can't get at it; moisture can't get into it. I have used rolls that had lain so long in damp places that they were all moldy outside, yet the food within was neither worse nor better than before.

A pound of erbswurst, costing from thirty-two to forty cents [$5.36 to $6.70 today], is about all a man can eat in three meals straight. Cheap enough, and compact enough, God wot! However, this little boon has a string attached. Erbswurst tastes pretty good to a hungry man in the woods as a hot noonday snack, now and then. It is not appetizing as a sole mainstay for supper on the same day. Next morning, supposing you have missed connections with camp, and have nothing but the rest of that erbswurst, you will down it amid storms and tempests of your own raising. And thenceforth, no matter what fleshpots you may fall upon, you will taste 'dynamite soup' for a week.

Kephart is being a bit unfair, in that his is a complaint anyone would make if he had to eat pea soup for an extended period. I tend to make fresh split pea soup at home, but can never seem to bring myself to finish off the leftovers. I added this entry with some misgiving, mainly because "dynamite soup" is no longer made; however, it was the component of many "emergency rations" and has thus earned its place in history - or perhaps, in history's bowels! No matter, some form of pulverized, dehydrated soup was a component in many "iron rations" in the 20th century, and the same recommends itself nowadays.

Hardtack, Kanpan, Geon Bang, Pilot Bread and Dauerbröt

We've all read the horror stories of how awful hardtack is. I've tried it and they're mostly true. Modern versions like "Sailor Boy Pilot Bread" (about which more later) are generally made somewhat more palatable at the expense of indefinite shelf life.

Shelf-stable "breads" such as hardtack and other such "biscuits" have been a component of the Iron Rations of most armies throughout modern history. Japan is no exception, and their version - an apparent copy of the "Zweiback" of World War II Germany (not the same as that sold for teething babies) - is called kanpan. Koreans call their version Geon Bang - pronounced "gyohn p'ahng" - and it's made with barley.

The several nations used these little crackers identically, which was to issue them out as part of a "cold" or "marching" ration. They were sometimes given out in paper or cellophane bags. More often, a soldier was given a cloth bag about the size of a child's brown paper lunch bag, which was refilled from a common stock, returned and sanitized as needed.

You can still get the stuff at (where else?) Amazon. Amazon makes it easy to find things I might like to buy "on the economy" and then figure out where I might find them. Something tells me I'll run across these in Chinatown.

Sharpie and shades shown for scale

The photo shows the two kinds which arrived at my office yesterday. The one on the left is from Japan and the one on the right is from Korea. The Korean kind came in two packages the same size (for the same weight, more or less, as the Japanese kind) but by the time I took the picture, I'd already gobbled up one of them.

I'm getting ahead of myself...

The two brands of crackers are identical in size, shape and appearance but differ considerably in taste. Both kinds are easier to munch on than Pilot Bread, though they are still made to withstand long storage and rough handling. The Japanese kind is pleasant but plain. Except for a tiny bit of salt and the possible existence of a few caraway seeds, they are unseasoned and appear to be little more than a more robust, bite-size saltine. The Korean ones taste far better. They have the same texture and other physical particulars as their Japanese counterparts, but are made from different grains and are agreeably seasoned. Not in a flavor any American would readily recognize, but a sort of savory-salty taste that would pair well with anything from smooth cheese to tinned fish. I hope my favorite Chinatown grocery store sells the Korean kind.

Enough has been said of hardtack - like erbswurst, it has its place in history, and ought to remain there. You can find recipes to make it online, and "cookie-cutter" molds to shape it, if you like. A better version is "Sailor Boy Pilot Bread," which is almost the same but with just enough fat to make it easy to eat - something hardtack is definitely not. Pilot bread is available on Amazon and, so I'm told, darned near everywhere in Alaska. All things considered, Amazon is easier - if you live in Alaska you already know all about them. I've eaten Pilot bread a few ways, all recommended by my Canadian friends who are well acquainted with it. It complements any spread as well as a saltine would, with less salt. I've also fried them in the bacon grease left over from breakfast so as not to waste it. Cream cheese on bacon-grease fried Pilot Bread is genuinely delightful.

The Germans, for their part, put considerable thought and variety in the bread component of their "iron rations." They had the "Zweiback" crackers mentioned above (which are identical to the Japanese version), but they also had several additional breadstuffs for their soldiers, many of which are available today. They'd get a daily fresh bread issue from a field bakery, but as it is outside the scope of this article it won't be discussed further. Among the "iron ration" breads was something they called "Hartkeks" which were a darker version of the "Swedish crisp-bread" you can get in the "International" section of better supermarkets, and something they called Dauerbröt which deserves a bit more attention.

Loosely translated, Dauerbröt means "long-lasting bread," and refers more to a category of bread than to a specific flavor or grain. It is a "soft," dense, somewhat dry, crustless bread without leavening or fat, double-wrapped and sealed for long shelf-life. It's still made by various companies in Germany - notably PEMA and Mestemacher - and like the "Swedish crisp-bread" mentioned before, you can usually find it in the "International" aisle in 500g (1.1lb) loaves.

Two different brands of "Dauerbrot," Pilot Bread and MRE breads - "Wheat Snack Bread" and Crackers. Soup can for scale

It's not called Dauerbröt on the shelves (this was a wartime term), but usually something like "whole grain fitness bread" or something equally German-sounding.

Its lack of fat and yeast leaves it dry and dense. It's best with a soup or stew of some sort, or smeared with mustard or jam or some sort of paté. One trick is necessary to know about it. The loaf comes in slices about 1/8-inch thick; but its preparation and packaging is such that you can't just grab a piece. In order to be separated cleanly, slide a knife between slices or else the slice you're grabbing will break.

As to taste, it's different from breads found in American stores or bakeries. We are used to light, fluffy, yeasty breads like those in France and Italy, and we like our crusts soft. Germans like this stuff too, but their bakeries also carry darker breads we often shy away from, in particular ryes and pumpernickels. Germany shares this taste with most of Eastern Europe, whose breads are very hearty.

In order to satisfy the curiosity of those looking at the picture above, the two foil-packaged breads come from an American Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE). The crackers taste exactly like the pilot bread discussed above, and the "Wheat Snack Bread" is exactly what you'd expect a one inch-thick bit of wheat bread with crust all 'round it to taste like if it were compressed, vacuum-packed and stored for a year. It's an amazing technical feat, wholesome and not unpleasant tasting; but it's just alien enough that you have to use imagination and Willing-Suspension-of-Disbelief when eating it. In the end, it is slightly disappointing.

Meats, spreads, everything else...

Modern military rations the world over have mostly taken their cue from the American MRE. These have been around for at least 35 years and their biggest improvement on military rations is the form of their packaging. Cans are out, replaced by foil-and-plastic retort pouches. The civilian market sees these most often in single-serving packets of tuna, but it's safe to say that most foods in durable plastic pouches with easy-open tabs on the sides take their hint from MRE technology.

It's hard to overstate how big an improvement these pouches are from a military perspective. Not only are they lighter than the can of the old C-rations for a given portion, they are easier to pack, easier to store, easier to heat up, less wasteful of food and, most importantly, create less volume of rubbish (an important tactical consideration).

But in their time, canned rations were an even greater improvement. They made such things as standard portion sizes, food safety, long-term storage and durability possible which simply didn't exist before. We are much farther away in technology than we are in time from the days when armies in the field kept large herds of animals "on the hoof" because there was no other way to ensure fresh, wholesome meat for the troops, and when vegetables could only be had by foraging if you knew what to look for.

In other words, canned food is a REALLY BIG DEAL.

Even now, many countries still issue some of their rations in small cans, despite the advantages of state-of-the-art retort packaging. Some of the reasons include:

- Cost - it costs far less to provide an off-the-shelf food than to develop new menus (MREs are expensive and much of the cost goes into keeping the menu varied, as well as the packaging technology).

- Availability - MREs are made by one or two contractors in the United States, and most countries with a similar ration have a single domestic contractor making their own. Countries who decide to use off-the-shelf canned items (the French, Russians and Germans, for example) can very quickly let contracts to any number of existing companies who are already making their foods for commercial sale.

- Morale - One thing an MRE is not is familiar. Even after more than a generation, most Americans have never seen the contents of an MRE up close and personal, and eating one is an alien experience. Candy items placed in an MRE are almost always off-the-shelf because everyone is familiar with them. In the same way, soldiers of all countries are familiar with canned products from their own groceries, and the presence of familiar foods in friendly packaging when far from home is an element of morale.

From the time of the American Civil War, canned goods have been a part of the soldier's ration, and excepting the few commercial items offered in modern retort pouches, no one has figured out a cost-effective way to improve on keeping prepared meats wholesome besides metal cans, jerky or hard sausages.

Which leads us back to the international aisle, where you will likely find a number of different patés, usually in small cans remarkably similar in size to the little cans of Armour-brand vienna sausages.

Soup can for scale. The sausage can in the upper left is still sometimes issued in the Army's "UGR-A" box lunches.

These all - including the vienna sausages - have their origins in military canned rations. Most canned meats do. The corned beef we see in the grocery store next to the Spam (also widely used in World War II) was itself a staple of all the Western Front nations of World War I, known in English as "bully beef," a corruption of the French "boeuf bouille." For their part, the French called it "singe" or "monkey meat" because the brand-name on their cans was "Madagascar," and they half-jokingly reasoned that monkey was a likelier import from thence than beef.

Everyone reading this already knows everything they need to know about Spam and "bully-beef," certainly enough to have formed unwavering opinions of them, one way or the other. For my part, I keep both. About the only thing I make with bully beef is a sort of fried rice wherein I brown a can of corned beef, adding whatever seasoning I feel like (usually Chinese hoisin sauce and a dash of sriracha), then mixing the rice in and occasionally adding green onions. I mention it here only in defense of corned beef generally, and not as a recommendation for an iron ration - a 12-ounce can is too much for one person to make in the typical backpack mess tin lid.

As for the various patés, they are all a variation on the can of deviled ham in the upper right. One is chicken and the other is pork. I think they come from Croatia or somewhere. The bigger can at left front is Armour's Potted Meat Spread, which tastes exactly like it sounds and is an even better candidate for the term "monkey meat" than the stuff the French had. They are all very salty, just like deviled ham, which is either a good thing if you're doing heavy, sweaty work; or a bad thing if you have high blood pressure.

The Germans did something I haven't seen done by any other army. They issued their soldiers a covered dish about an inch deep and four inches in diameter, into which was served any of a variety of fats - not chiefly for cooking, mind you, but for spreading on breads. These could be butter (increasingly rare as the war went on), lard, something called "schmaltz" which is exactly as appetizing as its name, or whatever fat the cooks had left over after breakfast. In a military context, it makes a sort of sense; but as a preparedness item, there seems little point in repackaging something like a fat in such a way that it will ultimately go rancid.

German "butter dish," circa 1960s-1980s

Can added...you know...

Everyone Loves Candy

By World War II, most every nation understood that in addition to meats, starches and vegetables, the soldier also needed sweets and acidic items in his diet. Each nation tried its best to meet this need. All nations usually had at least a sugar ration, either white or brown.

The British generally included various types of jams and marmalades in their rations, and it was a good idea - candies were something most soldiers would receive from home or from relief societies.

Americans were issued LOTS of sweets in World War II. They had various drink powders in their rations, as well as several types of candy, most of which were designed especially for their rations and many of which are still with us today - Tootsie Rolls and M&Ms being the most well-known. They also had "D-ration bars" which were something like an energy bar of today, but much less tasty. A modern version has been included in American rations since about 2007 or so.

Germans had hard candies, some marmalades, chocolates (especially a caffeinated one called Scho-Ka-Kola which is still made), something similar to Nutella, and dextrose tablets. If you want to know what these last tasted like, go to the convenience store, buy a "Lik-em-Stik" pouch and just eat the white "stik" - they tasted exactly like that.

The Russians provided what candies they could, but had to rely mostly on Lend-Lease shipments for fruits.

The Japanese soldier relied upon forage or packages from home for the most part, as issued quantities of vegetables, fruits or sweets was sparing, though he was regularly given sugar. One exception was a sort of candy bar made out of brown sugar, nuts and sesame seeds.

The Chinese sell a version, pictured above. This package is about the size of the box of candies you get at the movies, and a bit thicker. It is VERY heavy for its size, and the taste is...foreign. Very sweet, but not the sort of thing most Americans would associate with "candy." It meets the chief condition of a civilian preparedness emergency ration in that it tastes good, but not so good that you're inclined to tuck into it when there's no emergency. It's also very temperature-stable - it doesn't melt.

Vegetables seem to be the hardest to include in an "iron ration," and it's an open question whether they even belong there in a preparedness context. Note that "iron rations" were ideally only meant as temporary support. That all "combat rations" are over-utilized everywhere (even nowadays) simply shows how difficult it is to get centrally prepared food to soldiers in combat. In putting up rations ourselves for, say, three days' time, one can make a case either way. It's even more important if dietary restrictions prohibit a meat component, but this is up to the individual. On the other hand, dried fruits are plentiful, nutritious, help keep one's innards in proper working order, relatively inexpensive and shelf-stable. They are very much worth the space they take up in the pack.

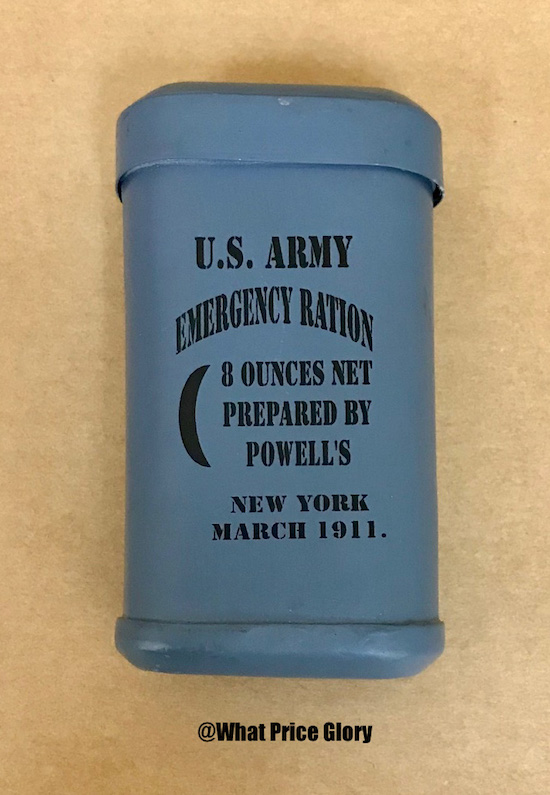

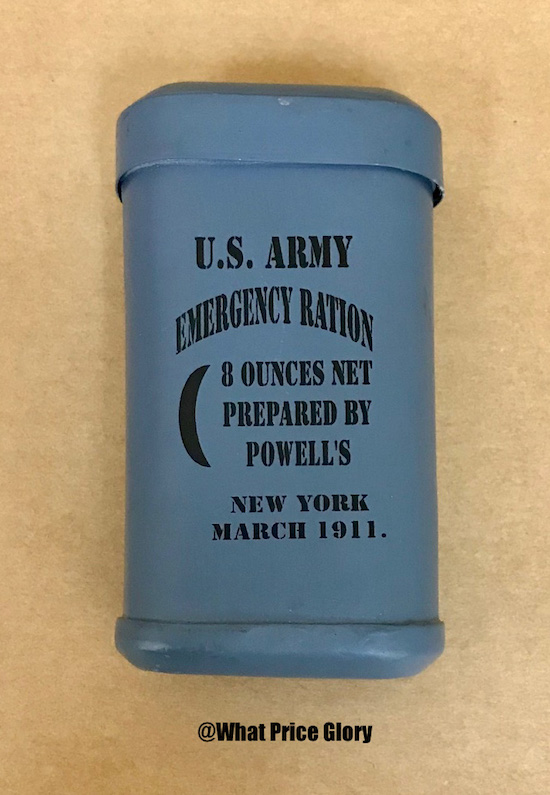

The Good Idea Fairy Visits Uncle Sam

By 1910, America had a good system of feeding its troops - certainly from the perspective of nutrition. The only problem was it wasn't tested in the trenches of the Western Front, and we see that many of the good ideas and innovations America had with respect to feeding an army in the field were no more than wishful thinking.

Our emergency ration, for example, started off from a great idea. Long before 1803 when the Lewis and Clark Expedition set out, America knew how valuable jerked meat and "Pinole" were as lightweight iron rations. Everyone knows what jerky is - pinole is simply corn, parched or browned in a skillet, and then ground to a coarse powder, as through a coffee grinder. Sounds awful, but it isn't. It tastes somewhat like popcorn, is unbelievably filling and since it uses the whole kernel of corn, is very nutritious. Its only drawback is that it must be taken with copious amounts of water, but we need that anyway. I made a few pounds of the stuff many years ago, and can attest that while it's "good and good for you," you'll gag if you don't immediately wash it down. The War Department (forerunner of today's Defense Department) knew all this as well as anyone in the Republic could. They also knew the value of chocolates in an emergency ration, as they are a good way of keeping fats wholesome over a period of time. Lastly, they also knew everything there is to know about pemmican, the Native American winter food staple.

You'd think it would be simplicity itself to put up a day's emergency ration, weighing no more than a pound, containing a quantity of jerky, pinole and chocolate, wrapped up so as not to corrupt each other, done up in a waxed paper or oilcloth package and kept on hand. That's what they did, right?

Well, no. That's exactly what they DIDN'T do.

The result of all their study was to dehydrate - not jerk - lean beef, pulverize it and mix it with flour rather than parched corn, press it into cakes, and then seal the cakes, with some chocolate and a small amount of salt and pepper, in an airtight metal can the size of a tobacco tin.

Photo of reproduction from vendor - I don't own this.

One need not even taste the resultant concoction to realize they'd taken away everything good from jerky and pinole and substituted something that was worse than the two existing ingredients by themselves! The foods invariably tainted each other, they were without real nutritive value, tasted bad, were hard on the digestion, and all of this when a soldier was exhausted, under stress and hungry.

The Department of Agriculture proved how inadequate it was nutritionally, and by 1913 it was discontinued in favor of a slightly better emergency ration that had bean flour added to the cake, with raisins replacing the chocolate. It was a little closer to pemmican but still not a success. The War Department may have done just as well, saved considerable money and settled Joe's nerves as much by simply giving him a pack of cigarettes instead.

To this day, the idea of a pleasant-tasting, comprehensive one-day emergency ration of a reasonable size and weight eludes the brightest minds of American business, though the science and practical application of such a ration has been known for more than a century. It may be that the demand for such a thing does not exist in sufficient quantity to justify commercial innovation. Lifeboat rations, for example, are bland and don't look one bit like food; but they already exist, they already work, their cost is reasonable, and maritime casualties are seldom marooned very long anyway. The closest thing I ever saw to the ideal American iron ration was at a mess hall in Iraq, where instead of MREs (I never saw an MRE in Iraq on either tour), packets of Gatorade, jerky, trail mix, hard candy and Pop-Tarts were laid out for soldiers to shove in their pockets. Sometimes the best ideas are the simplest.

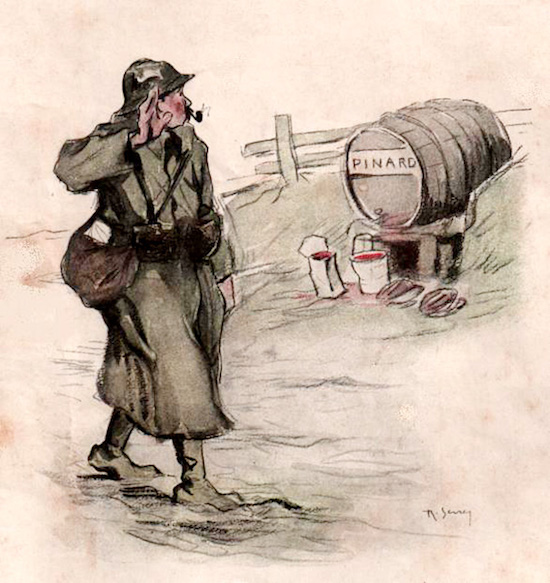

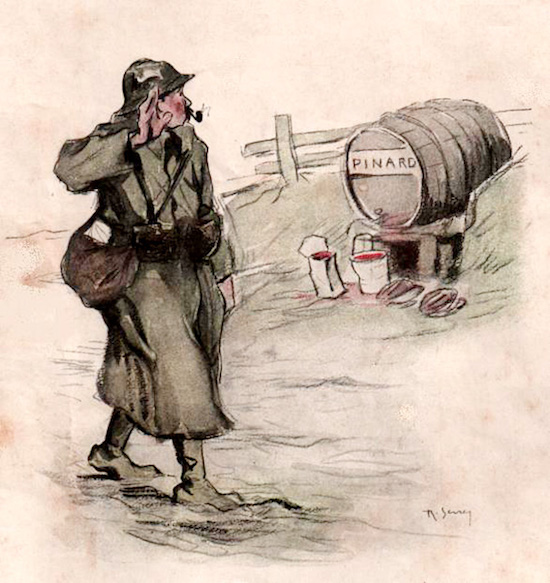

Git Yo Drank On!

No discussion of marching rations would be complete without touching on the different ways the world's armies "civilize" their water. Almost invariably, it was in the form of coffee or tea, though powdered fruit drinks began to show themselves toward the end of the World War II. We also see in Germany, as in the Confederacy during the American Civil War, various coffee substitutes, most of dubious quality. Nowadays, instant coffee of passable taste is easy to find, and tea bags, while inferior in many respects to loose-leaf tea, is as convenient as it gets. Cold-drink powders exist in such variety now that it's simply a matter of choice.

However important alcohol was to the soldier, it was as a matter of policy only issued at times when regular rations were available. Alcoholic drinks were generally not a part of any nation's "iron rations," so they won't be discussed further.

Thoughts on cooking this stuff up

We've already discussed the difference in attitude between the Imperial Japanese Army and most of the rest of the world with respect to cooking meals in the field. Every nation issued some sort of metal mess kit to its soldiers. But while these kits were designed with some sort of simple cooking in mind, soldiers were not expected to do much cooking with them. Stands to reason, really. If they're not fighting, then feeding them from a common mess by trained specialists is cheaper and healthier; and if they are fighting, they've got more important things to do!

Still, there are always those "in between times" where they aren't busy blowing each other to bits, but the chow-wagon still hasn't caught up to them. Most cooking in these conditions happened at the squad or vehicle crew level, either using a few common large vessels (a practice which goes back to Roman times) or putting their mess kits around a common fire pit with one soldier detailed to see to everyone's grub. British and German field manuals from both World Wars and somewhat earlier show methods for doing exactly this, and first-hand accounts likewise point toward food preparation in groups rather than individually.

The design of various mess kits (now largely disused and surplus) said something about the culture whence they came. Most European mess kits look like the German version from both World Wars - a kidney-shaped stew-pot with a smaller pot answering the purpose of both a lid and a bowl of sorts. In use, they would hold a stew in the bowl, and meat or cheese or bread in the pot (or vice versa, depending on which was more plentiful in the chow line).What cooking was to be done with them was normally goulash or porridge of some sort, made with whatever was on hand.

The British mess tin of World War II vintage and after was two pieces of rectangular aluminum, both with handles, meant to be used as above, but Tommy was also provided with a "stove" that was a sort of Sterno can with a frame, which he could set one of the tins on to warm up whatever it was needed heating. Many NATO armies copied this arrangement, just like many armies copied the Germans' "Kochgeschirr."

The American mess kit - originally called a "meat can" - was meant almost exclusively as a plate for prepared food, except when the soldier had bacon to fry up. No proper cooking except frying can be done in it. All frying in any mess kit was of the skillet style - mess kits are not for deep-frying.

The "Mountain Cook Set" of the U.S. Army is the closest thing to a decent set of field cookware ever put out, and it was intended to be used with a gasoline-powered stove. An older version of the Army's cold-weather manual - FM 31-70 - discusses cooking at the squad level, in a manner somewhat similar to the German and British field manuals which cover the same topics. The difference was the U.S. Army's concept at the time revolved around prepackaged rations similar to their "5-in-1 ration," which was developed for vehicle crews.

So the notion of soldiers cooking regularly for themselves is something of a misstatement. The Japanese excluded, they did so only when they had to, not every day. Also, we only lightly touched on such things as seasonings, meal planning, utensils and other facets of cooking outdoors.

The reasons for this are self-evident. First, soldiers already carry too much stuff, and they have carried too much stuff since "Marius's Mules" of the Roman Republic. They learn very quickly what can be left behind in the regimental "trains" or discarded entirely, and specialized cooking utensils, spices, garnishes and so forth are among the last things a soldier will make room for in his already overloaded pack.

Next, it's only within living memory - that is, World War II veterans and later - that "soldier comfort" was given any priority to anything besides maybe his boots, and even these were only carefully thought of in the U.S. Army starting around the First World War. Cost, durability and fitness-for-purpose (often in exactly that order) were the prime considerations when a nation looked to fit its soldiers up - comfort simply didn't enter into it. Good cooking gear and an abundance of "fixin's" are even now simply not thought necessary.

Lastly, it must be restated that food preparation is at best secondary to everything else a soldier has to do. He's not in the field for leisure's sake, as in backpacking - time spent cooking is time not spent digging fighting positions, covering a field of fire or maintaining his gear, presuming he's not actively engaged in combat. Above all, the soldier's iron rations had to be simple.

How Did Soldiers Carry All This?

Most armies had "bread bags" which were nothing more than modernized versions of the "haversack" satchels that date back to the English Civil War. They were carried on cartridge belts or backpacks, and were essentially a lunch bag. Iron rations often went in these; at other times, they were carried in their backpacks, which discouraged getting at them whenever one wanted - remember that "iron rations" were only supposed to be eaten on an officer's orders. In the case of the Germans, their iron rations went in a small pouch that attached to a sort of frame which also held their tent sections, blanket, mess kit and so forth. This made them even harder to get at and one researcher believes this was to discourage "the munchies" even further.

Their individual portions were normally packaged in cans or bags of various materials - paper and cellophane for the more industrially advanced nations in WWII, with simple cotton bags as fallbacks, or standard issue for everyone prior to WWII. British rations were mostly canned or boxed; unlike the Germans, who assigned a place on their gear for every item, the Brits tended to carry their rations wherever there was room in their packs. American rations in WWII were all cans or cardboard boxes. K-rations were designed to fit in a uniform cargo pocket, though they were often carried elsewhere like the Brits, and C-rations were usually carried by a vehicle of some sort, then man-packed up to the Soldiers at mealtime or when conditions permitted. Soldiers who knew they'd be separated from the field kitchen for an extended time also stuffed their mess tins, pockets, or even carried things bucket-like in their helmets. Later in WWII, the Germans experimented with their own version of the K-ration, having seen how highly their soldiers thought of captured American rations - in WWII, everyone ate off each other's plates when they could!

Looking at adapting these rations to our own use, there are simply too many carrying and packaging options to list. However, some general guidelines are worth considering:

As a general rule, keep re-packaging to an absolute minimum. We take safe food for granted. This wasn't always the case, and even less so in the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. Food-borne illness was the lot of the average soldier of the period - the "Old Soldier's Sickness" accounts for many of the non-combat deaths of all soldiers prior to WWII, and is one reason soldiers in old photographs look so skinny. Modern food processing practices keep our foods safe until we bring them home and open their packaging. It follows that we should not repackage our foods unless absolutely necessary. Canned foods, if we decide to include them, should never be opened until they are to be used. Sealed packages of single-serving portions likewise should usually be left alone, as should anything like the Dauerbrot, chocolate bars or the Chinese "Brown Candy," which are packaged as compactly as possible. Dried fruits and spreads are sticky, and should also be left in whatever they came in - look for items with convenient packaging.

This leaves bulk items like Pilot bread (2-pound boxes are too big), the kanpan type crackers and bulk grains. Pilot bread can be re-packed in any 4" canister provided it's clean and dry. Metal coffee canisters will hold about two days' worth, and the can will be useful for something when it's empty. The kinds of cardboard canisters nuts come in will hold a day's worth, as will 16-oz dairy tubs for chip dip, sour cream and the like. Wrapping the crackers in wax paper before putting them in the can will provide additional environmental protection and guard somewhat against breakage. Kanpan-type crackers and bulk grains can go in anything from plastic baggies to cloth "pokes," so long as the latter are clean. The average issue for the crackers was about the size of a paper lunch bag, and a single serving of any of the grains we discussed in this article is a "rounded" half-cup. It's up to you whether you want to keep the grains in bulk or have them in single-serving portions.

Conclusion

Iron rations in a military context belong to a period in history that saw modern innovations in simple, hardy, shelf-stable foods coexisting with horse-drawn, wood-burning field kitchens, and field bakeries using packed-earth ovens. The march of progress has rendered these facilities obsolete militarily. The modern combat ration most armies now provide takes the place of the iron ration, and makes the emergency ration largely pointless.

Military obsolescence is not the same thing as civilian obsolescence. There is still a need for things like the iron rations of old. People may not care for modern, freeze-dried camping meals or military rations, which are also more expensive. People may prefer more basic staple foods. Any number of reasons exist for studying the sorts of things soldiers ate and how they made them.

As for me, what would a typical iron ration look like? It depends, but a notional ration for one day in a preparedness context may look like this:

Breakfast:

- Kasha

- Summer sausage

- Half a small cheese wheel

- Dried fruit

- Coffee

Lunch:

- Raisins

- Nuts

- Paté on Pilot Bread

Dinner:

- Rice with tinned fish

- Other half of cheese wheel

- Chocolate bar

- Tea

As with all things, learn what's best for you and adapt accordingly,

Additional Reading

Concentrated Foods

The last word in this essay rightly belongs to Horace Kephart, whose book "Camping and Woodcraft" I quoted earlier.

Much of what mankind knew or thought he knew when Kephart compiled his book in 1918 has been found to be incomplete, outdated or outright wrong - next to nothing in his "medical" advice should be listened to, for example. But when it comes to nutrition in the woods, especially when "going light," it is no exaggeration to say that you will learn more practical fact from this one chapter of Kephart's book than you could find in a mountain of online articles.

The chapter is presented in serialized form, in four parts. A link to each proceeding part is at the bottom of the first, and so on.

If you read nothing else in this essay and only spent time on what this link had to say, your time would be wisely invested and you'd be far smarter for it.

https://bookdome.com/outdoors/Camping-Woodcraft/Chapter-X-Concentrated-Foods.html

gvi

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2019 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.