How our colonial ancestors went at the problem

*Packless Pack for Day-Trips*

By: GVI

29 December 2023

The hint for this project came from a thread on a bushcrafting forum of which I'm a member. It was written by a Norwegian who fitted out a rucksack for day-long hikes with his dog in their version of the backwoods. Honestly, I liked the dog pictures better than the kit pictures. But everyone seems to like "gear porn" and, in addition to the "retro" look which appeals to everyone on the bushcrafting forum (I'm no exception), his gear was wisely selected. There was nothing that didn't belong there for his intended purpose. It was fair-dinkum kit, and with just one exception I found it entirely satisfactory.

That exception was the pack itself. It was some greyish Scandinavian surplus canvas thing with a stout frame; and once all the guy's impedimenta was stuffed in it, it was no more than half-filled. It reminds me of the stale old joke that the optimist sees the glass half-full, the pessimist sees it half-empty, and the engineer sees a glass that's twice as big as it needs to be.

No one with any sense argues the prudence of a backpack for long trips while dismounted. The only things worth talking about are whether the pack is the right size for gear and bearer, not unreasonably heavy for its volume, and whether it is comfortable. Chez GVI has more backpacks than it has backs to put them on - I suspect many of us can say the exact same thing. For being out several days or longer, a backpack of some description is essential.

But what about those times like this fellow's, when we're only going out of a day or simply overnight - is a backpack always necessary?

I submit that sometimes it is not.

This article is not a discussion about gear, quite so much as it is about how to manipulate our gear so as to make yet another bit of gear unnecessary. In other words, we will be talking about fashioning what we have into a serviceable pack that needs no further baggage - the gear becomes its own pack.

If we are only going out for a short trip - whether in civilized society or during a longer outing - it's wise to take only those things we have good reason to know or presume we'll need. Moreover, everything we take ought to serve a purpose once we get wherever we're going. For all its utility, a backpack does little more than comfortably hold all our stuff in one place and organize it somewhat. If we've set up a secure site we're happy with and plan to return to, striking camp and packing everything away just to go out for a short spell is wasted effort. And few backpacks "ride well" when only partially filled. Carrying a second, smaller "day pack" might be an option, but it might also be more weight than it's worth. The more we know, the less we need to carry; and making a pack out of stuff we're already using frees us from the need to carry a secondary pack that may or may not get used.

This is not a new problem. From time immemorial people have gathered their things up and carried them without packs, the results either being workmanlike on the one hand, or slovenly on the other - a hobo's bindle comes to mind as an example of the latter. Since this problem is not new, it's worth the trouble to look across time, place and culture at what others have done along these lines. Several solutions present themselves:

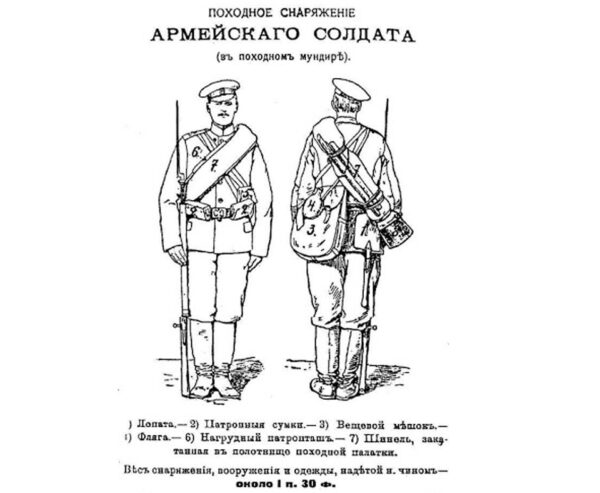

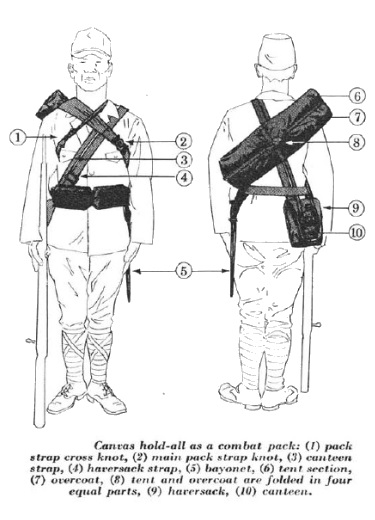

How our colonial ancestors went at the problem

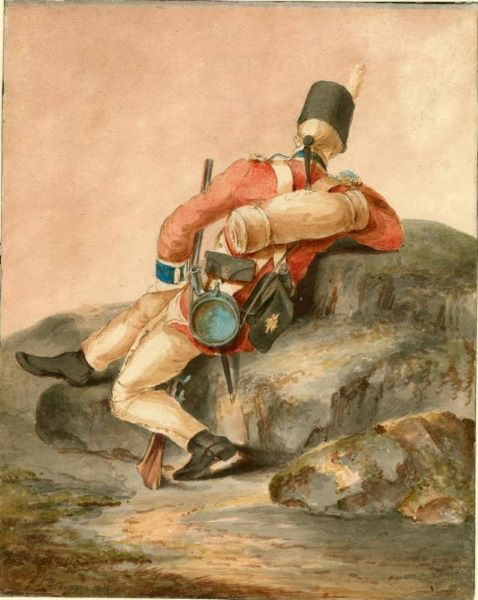

Not an auspicious first attempt

He's starting to get the hint

This fellow's horseshoe roll is made not with a blanket but with a wool greatcoat

For my part, I dislike "horseshoe rolls" such as Russians and Civil War reenactors use. I've worn one when re-enacting with a friend. I find it profoundly disagreeable - annoying to wear, hot and constricting, and you can't put much in it. Re-enactors are bound to come out of the woodwork to tell me my dissatisfaction was because I did it wrong, or tell me to suck it up (or whatever the 19th century equivalent is for this phrase) and learn to live with it…

Nonsense. If there are several methods for achieving a given end, and all else is equal, those methods which are easier to do well are superior to those requiring more "knack."

I can't make you not try the horseshoe roll. Who knows? Maybe you can make one easily and carry it comfortably. As for me, I note that the horseshoe roll is well established in the faded, dusty back-pages of bygone history, and this is exactly where it should stay.

Returning to the bushcraft discussion that started this line of inquiry, several members expressed astonishment when I shared a link to a photo essay that showed how much a soldier typically carries on campaign. Putting it bluntly, they were appalled. They didn't need to point out to me that hiking experts going back to the 1800s advocated and demonstrated the ability to take days'-long trips afield with no more than 25 pounds throughout the camping season, including food. But since it's the internet, they did just that - several times over. The fact that a soldier's kit has to last him throughout an entire war (and not merely a few days) had never occurred to many of them.

May the Lord bless and keep these sweet summer children in their innocent ignorance.

Worth considering, however, is the similarity between the "bushcrafter's" loadout and what eventually became known as the soldier's "approach load;" that is, what a soldier needed for the day or so he may be away from the rest of his baggage. These two concepts are close enough in premise to make meaningful comparisons. This idea is likewise very old - Julius Caesar hints at something like it a few times in his "De Bello Gallico;" and though he brags about how clever he was to think of it (all autobiographies are self-serving), he was far from the first. The "approach load" came to a recognizable form in the American Revolutionary War.

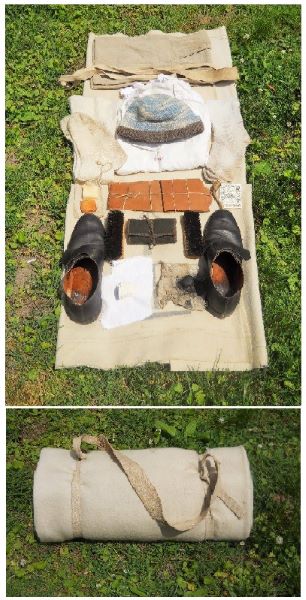

This loadout (in fact somewhat less than this) is referenced in orders to the Brigade of Foot Guards when they landed at Sandy Hook in August 1776

What it looks like all rolled up

I think this soldier was serving in Wellington's "Peninsular" army but I'm not certain

It worked for the Redcoats in 1776 - history informs us they landed without incident and received their "sustainment load" according to plan the next day. The same thing was tried nearly 70 years later, with much less success, when a large Franco-British expeditionary force landed at Calamita Bay in 1854 to kick off the "ugly" phase of the Crimean War. The landing itself was successful, catching Russia completely flat-footed. But it took several days for the soldiers' baggage and stores to make it ashore. Their cold-weather gear never did make it (the supply ship sank), with disastrous results - but this was a failure of logistics, not an indictment of the idea of traveling light when it's prudent.

By the time of the Great War many - though not all - of the world's armies adopted the "Approach Load" concept, some better than others. The Imperial Russian Army didn't bother with an "Approach Load." Why should they, when their soldiers' entire kit-and-clothing-issue was far less than what many nations considered the barest minimum for existence?

Everything an Imperial Russian soldier signed for (wire cutter and grenade were not universally carried)

This is much less than many armies would send troops out overnight with

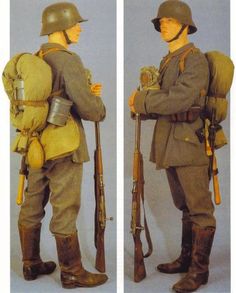

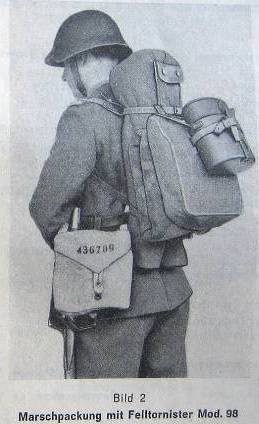

The armies who experimented with an "Approach Load" all came up with more-or-less the same list of items they considered an irreducible minimum, and it bears considerable similarity to the inventories we prepare for 3-day "get-home" or "bug-out" bags. The principal difference in each army's "approach load" lay in how this minimum was arranged and carried. Some had the ungainly "horseshoe roll," some - like Imperial Germany - took the horseshoe roll and simply moved it elsewhere.

This setup is as bulky as the Landser's "schwere Affe" tornister pack, but it's much lighter.

This gave Germany the hint for its "A-Frame" assault pack in World War 2

An impressive amount of innovation came from a surprising quarter - Japan. After the Satsuma Rebellion of the late 1870s and up until about 1936, the Imperial Japanese Army was one of the most modern, open-minded and forward-thinking military institutions in the world (just like their navy), and their gear reflects this. By 1905, Imperial Japan came up with a clever sort of "assault pack" which was lighter than their European-inspired backpacks, worn somewhat like the horseshoe roll but also very clearly not the same thing. The idea stuck with them throughout their Imperial period - shown below is the form this seoi-bukuro or "tube pack" took by 1932.

Simple, inexpensive, durable and "just enough"

We'll discuss this item in greater detail in an upcoming article.

Around the same time as the Japanese were sorting out the final bugs on their own "assault pack," the Chinese (with whom they were at on-again/off-again war) made do with any of several packs made out of a blanket, stuffed with whatever the nation could scrape together, and held to their backs with whatever straps they could lay their hands on. In their wars against Japan, China's equipment was nowhere close to standard. In the 1930s, some units were as well turned-out as any European army, while others were lucky to receive shoes - to say nothing of rifles! If you can believe it, 1949 was the first time in China's several-thousand-year history where every Chinese soldier belonged to the same army. The military history of China is nothing if not complicated.

A staged photo

A Railroad guard - yep, China used swords in WWII

In the civilian line of "traditional lightweight packs," we have such things as the Australian swagman's roll, the cowboy's blanket roll (which we won't discuss because these were typically carried in the team's chuckwagon), the hobo "bindle" and the German "Charlottenburg" or "Charlie."

Let's spend a moment on this last one. It looks like a cross between the bindle and a trapper's tumpline pack. Germany had, and still has, the custom of the "Wanderjahre." This is a 3-year-and-one-day period where a journeyman travels around on foot (or presumably by public transportation), working on various projects, learning his trade as well as the value of good ethics, efficiency and thrift. The "Charlottenburg" or "Charlie" is a traditional means for the tradesman to pack his belongings and includes his own tools. It differs from the other packs discussed here in that its owner stays in civilized accommodations during his "Wanderjahre." It's not meant for sleeping outdoors as with the swag roll. I have my own opinions about German culture; and yet, I find this tradition charming and worthy of encouragement. Just goes to show you can't treat people wholesale.

I'd have thought the people of Saharan Africa or Asia Minor would have something similar, at least if I looked far enough back in history. Maybe they did and maybe they didn't - I can't find anything either way. It may be that I don't know the right search terms in their languages. It may also be that people in these regions never traveled alone and never without pack animals. After all, why carry a pack when the camel you're leading, in the caravan you're a part of, can do it for you? I just don't know; what's more, I don't know how to find out.

About the only central-Asians whom I can find using any sort of self-transported personal baggage are religious pilgrims, and the only ones who seem to carry a self-sufficient amount of kit are the Tibetans. Pilgrims in other places seem to carry much less (Jain monks don't even bother with clothing!), not only for religious reasons but also because they tend to stick closer to civilization - even today, most of Tibet can hardly be called "civilized." It's difficult to find anything about what religious travelers in this remote semi-nation carry, or how they carry it. If the photo below is any indication, it might also be that no one puts much thought or effort into it:

Their devotion to their faith may be laudable, but we can find better examples of good packing

Which brings us back home.

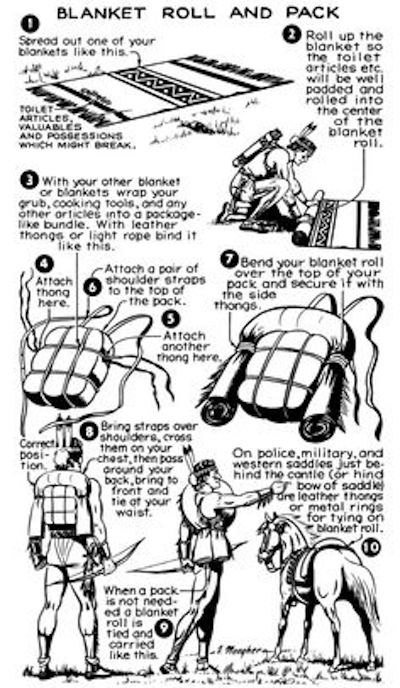

If the only resource you had for learning how to do things outdoors was 1950s Boy Scout handbooks, you'd be convinced that it had never occurred to the white man to carry anything on his back until some clever Indian taught him how. Indians figure prominently in mid-century American Scouting, whether they deserve to or not. Every field-expedient pack I've seen in old reprints of "Boys Life" ends up on the shoulders of some chiseled Noble-Savage-looking fellow in buckskin and pigtails.

See, lads? Them Injuns did it, so it's GOT to be smart!

I think there was a period in American Scouting where every author believed the only way to talk a boy into doing anything was to tell him an Indian came up with the idea. But I'm a cynical GenXer.

And I digress.

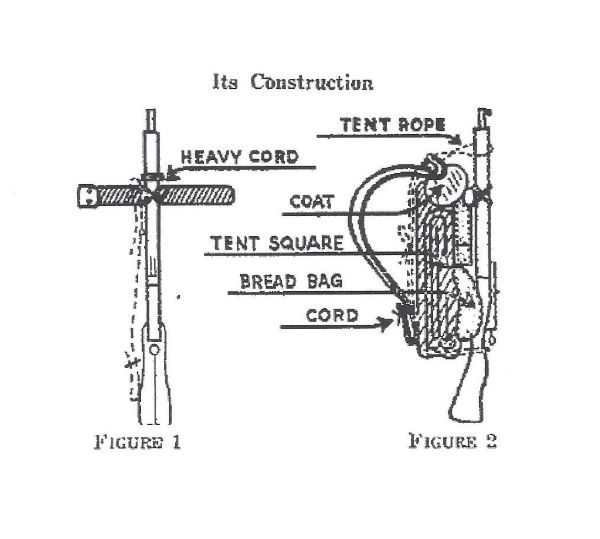

Of all the different "approach loads" I've run across - and I've looked at a fair few - the most workmanlike example is that developed by the Swiss. There are a few variations but they all revolve around the idea of making the "approach load" fit in a relatively narrow space on the back, freeing the arms for climbing/skiing, using only the equipment the soldier was issued. Theirs was the model I finally ended up imitating when attempting the same on my own.

A translated illustration of the pack and its assembly

A photograph of a slightly different variation

Like the Russians, both variations use the soldier's overcoat instead of a blanket. After all, these are "patrol packs." The Swiss rolled their wool overcoats in two different ways: "long" and "short." The "long" roll is what you see in the photo, and the "short" roll - originally to get the coat to fit in a special carrier for their bicycles - seems to be what is shown in the illustration. I have a surplus Swiss wool greatcoat. It's a fine coat but I'm not about to use it thus. A blanket is better, and in a future companion to this article, I show a few ways to turn them into useful garments while still retaining their function as blankets.

I should pause here and admit that this project is as much mental exercise as practical exercise. My goal was to prepare a pack that had everything I needed for a day's activities outside - whether that activity be a tramp in the woods or sitting on a lawn at an outdoor concert - and have as little as possible that didn't serve a purpose once I got where I intended to be.

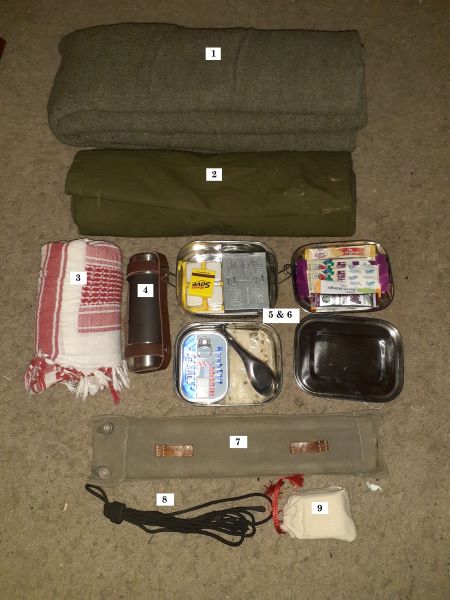

I ended up with the pack shown in the photo below, made up of the following contents:

This is what it looks like when worn

This is what's in it - numbers correspond to list above

The blanket is folded and rolled so as to make a compact upside-down U-shape. This is done by allowing a gap of 8" in the center; when rolled, this section is thinner and allows for folding the "long" ends of the U-shape down without bunching up. It's not necessary - just tidy.

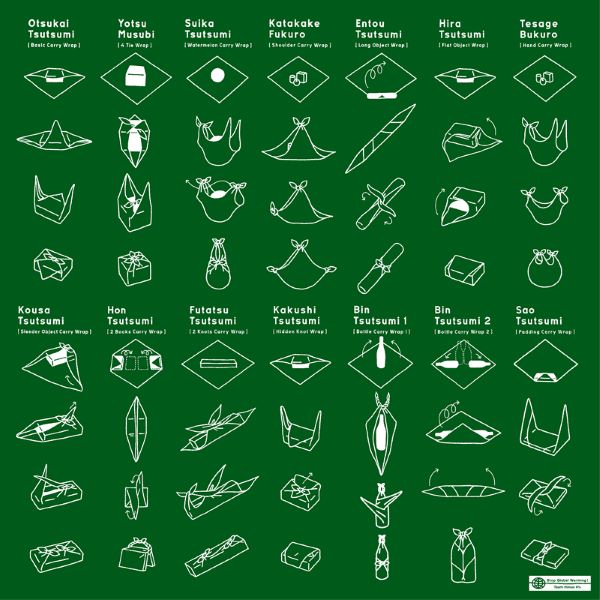

The Shemagh is meant to take the place of the soldier's bread bag, and is done up after the Japanese tradition of "furoshiki" wrapping. Its multi-use nature has already been gone into. Once done up as a tidy parcel, it and poncho/tent poles are lashed to the blanket with the 550 cord via a few half-hitches and a bowline.

The Japanese are pretty clever when it comes to stuff like this

The "Adapted" Alpha Loop is probably the only real innovation connected with this pack, and it's the reason it took so long for me to finalize. All Rubies have an Alpha Loop - a 10-foot length of nylon strap whose ends are stoutly stitched together - but this one is adapted to be somewhat more versatile yet.

Last year one of my friends from church - my daughter's former art teacher who does a LOT of world travel - showed up to an outdoor service with a strap across her shoulder, with which she contrived to sit cross-legged with a modicum of back support. It was beautifully woven and I asked her to tell me more. She couldn't, really, but she showed it to me and said the person who gave it to her called it a "Yemeni chair." I looked online and ultimately discovered that it goes by about a half-dozen other names (African Council Chair, Indian Campfire Chair and so on), none of which themselves return any image results either. You just have to get lucky.

Just my luck to get a preparedness idea from an art teacher

It's an Alpha Loop with one end left adjustable - a 10-foot long belt. The only thing left to be done to the Alpha Loop was to make it adjustable. It loses some small bit of utility if you're not good with knots optimized for straps, but these are relatively easily learned. For locking in as a "chair," simply adjust to the proper length, then feed the free end over and back through the "tri-glide" keeper as shown in the picture below. I discovered this trick after the umpteenth frustrating time my M16's sling worked itself loose. Once adjusted like this, it won't budge unless it's loosened on purpose.

This method will "lock" any strap in place until you purposely loosen it

From this, it was a matter of figuring out how to arrange it around the pack I'd just made up. What I came up with is loosely based on the Russian "Veshevoi Meshok" backpack - about as simple a backpack as was ever invented.

If a simpler rucksack was ever made, I've never seen it.

The bottom is wrapped 'round enough times to take up the slack. The top is made into a loop via an overhand knot and snugged around the top of the pack. The pack can then be carried in the normal fashion. Do as you please, but I've marked this white Alpha Loop at the lengths for each of several uses - this pack, the "chair trick," general-purpose Alpha-Loop use, etc.

This marking business saves a lot of hassle.

I used white "engineer tape" so it can more easily be seen - use whatever you like

There is nothing resembling real camping equipment, such as the tomahawks and elephant-gutting knives without which no self-respecting "bushcrafter" considers himself fit to be seen in public. Then again, I don't consider myself a "bushcrafter." Besides, much of what "bushcrafters" appear to do and go in for might be better called "woods-LARPing" or "backwoods cosplay." This project was primarily for going out in civilized society, and short of a zombie apocalypse no one needs a tomahawk in a city park or concert amphitheater. It's an example of how a thing may be done, not how it ought to be done - certainly not in terms of my "packing list." For example, there are ways to fold the contents inside the blanket such that the latter acts as the body of a sort of backpack, complete with flap. This is a method which invites creativity and exploration. In my case, with the exception of the poncho, few things in the list I provided really need to be "get-at-able" at a moment's notice.

Being a mental exercise as much as anything, little thought was given as to what ought to go into the pack's contents. I was literally thinking "What could I put together for an outdoor event that would make other guys' wives jealous?" My premise really was exactly that silly. But if we fancy ourselves preppers - mentally and in terms of skills, in addition to just having stuff - it ought to be simplicity itself for you to come up with some quantity of things you'd want for a short trip away from more permanent establishment. In other words, my "gear list" is irrelevant - make your own. It's just there to show what's possible; in doing so, I make no claim that it's the best way.

GVI

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2024 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.