You have to be in pretty bad shape to look like these two.

*Портянки, Fußlappen and Lots of Other Foreign Words*

By: GVI

27 February 2021

You have to be in pretty bad shape to look like these two.

Some preps are easier to make a case for than others. Having extra pairs of dry socks is one such. Having a way to mend worn or damaged clothing such as socks is yet another prudent measure. The importance of good boots which fit well and don't ruin socks in the first place is self-evident.

Convincing a Rubie he needs cotton or wool pieces of cloth to wrap his feet in is, reasonably, much more difficult than talking him into keeping socks, darning kits or boots handy.

This article will show how to make proper use of such wraps, but it will spend no time at all trying to persuade the reader that he needs to lay in a supply of them. Even I think this is foolish, and I'm the author! What I mean to get across, however, is the desirability of knowing how to fashion these things.

Why might you need to know this skill? Who knows?! One of the reasons we prep is to be ready for the things we can't predict. Look up "Black Swan" next time you're bored to tears. I shall therefore proceed, assuming my readers accept the premise that learning how to make and wear footwraps out of different types of material, either to act in place of or to supplement socks, is worth the trouble, without trying to sell them on the concept.

If you've read this far you don't need to be sold to, so you may as well keep reading...

This article is about primitive yet reasonably comfortable footwraps of two slightly different kinds, one square and one oblong. They take the place of socks in temperate weather, or supplement them in colder weather.

Go online and type in the word "portyanki" - which is what the Russian word in the title spells out - and you'll find plenty of references to this style of footwrap. The latter word, pronounced FOOS-lappen (that thing that looks like a weird letter "B" is a German letter representing a double s), is a German word meaning, unimaginatively, "footwraps." You can find plenty of information about these online as well. Most of these references are written for a certain type of WWII re-enactor; to wit, the guy who doesn't think he's having a meaningful "living history" experience unless he's authentic in places no one but his doctor or wife has any business looking. One wonders about the re-enacting community's opinion of "period-correct" lice, dysentery and V.D., without which no "living history" portrayal can be considered truly authentic. But I digress....

One deficiency of the several instructions you can find online for portyanki is that the really well-written ones are in Cyrillic, the Russian alphabet. It's bad enough to be an unfamiliar and bizarre garment; worse yet to be described in a foreign language - how much worse is it that they have to be in a different alphabet as well?! This article will provide a translation, as well as a link to a pictorial representation and text in English on wrapping the complicated portyanki - I think the presenter does a fair job, though the images may well put the reader off his feed. In addition, I will share my experiences with wearing both.

We can make all kinds of things out of next-to-nothing. We can fashion shelter from just about anything, contrive to make a fire at will, and find other makeshifts to keep ourselves warm and dry. But who can make a sock from expedients in a reasonable amount of time?

I know I can't. Knitting is how socks are made, and socks knitted by hand go back to time immemorial. But it takes time; and if I need something on my feet now, I'm unlikely to have the patience to knit a pair of socks up, even if I had yarn and knitting needles, which I haven't, and even if I knew how to knit, which I don't. I can, however, take pieces of cloth and form them such that my feet will be warm, dry and comfortable even if my socks can no longer serve their purpose.

There is much to say in defense of socks over footwraps. They're cheap and you can get them anywhere. They take seconds to put on, and no one needs to be shown how to do it - our moms already took care of that. They fit better without any real fussing or fidgeting. Perhaps most importantly, we don't have to give them a second's thought. Yet in extremis, the portyanka and the Fußlap have a few advantages over the sock:

...and we all know what that means.

Portyanki and Fußlappen are the product of European armies and European values. I know of no period in American history where our Army was issued anything other than stockings or socks. Those few times our Soldiers used some sort of swaddling for their "dogs," it was only as an emergency expedient in bitter weather, when no proper footwear was to be had. Since there was no standard to train to, or institutional memory of their correct use (the Russians have been using them since the late 1600s) the wrapping business was done haphazardly, and the result was unworkmanlike & uncomfortable. Images of American Soldiers with cloth wrapped around their feet are always intended to communicate suffering and privation - you will never find an image of a cheerful Yank with his feet swaddled in cloth. It is for this reason I've stuck with the foreign words; not only are they more descriptive than the relatively meaningless "footwrap," but they also imply a purposeful and more-or-less serviceable use of the items.

The two are similar in intent but different in approach. The German Fußlappen are easier to put on and easier to wear. Portyanki go higher up the leg (about the length of a short crew sock - that is, low- to mid-calf). The intent for both was to tuck the pant leg or long drawers over the wrap, and either don high boots with all tucked in, or low boots finished with leggings or puttees. Unlike socks, you can't walk around in just either; they must be inside some sort of boot, ankle high being the best in my experience. They don't work at all with ordinary shoes.

Being extremely primitive and simple, it follows that such "garments" were developed by peasant cultures in temperate and cold-weather regions. The examples I've found in research for this article are almost all European or Eurasian, and include the Romanian "obieli" which were used with a sort of simple sandal called a "Dacian moccasin" in English or "opanak" in Romanian. The Russians had a similar peasant shoe made of woven bast reeds called Лапти (pronounced "lapti"), and these were worn with a much longer version of the portyanki that's known as онучи (pronounced "onuchi"). These two terms are so obscure that at the time of writing, even Google Translate doesn't know what to make of them.

Footwraps are kept at the end of the internet.

I can find no examples of practical footwraps being used in East Asia or the Americas. This is not the same as saying such things never existed - I just can't settle the question one way or another. The abhorrent Chinese tradition of female "foot-binding" is best left in the moldering pages of discarded history - it will not be discussed here.

I have only ever worn portyanki to prove the concept and come to my own conclusions. These conclusions may be guessed at by the fact that I only ever wore them to prove the concept. I wear the Fußlappen somewhat more regularly, especially when cross-country skiing. I got my skis, boots and poles from a church rummage sale and the boots are a bit more than a size too big. Fußlappen allow for a better fit while at the same time keeping my feet warmer than socks alone. The most important part of donning portyanki or Fußlappen is ensuring there are no creases where the foot will rub against them, and this takes practice.

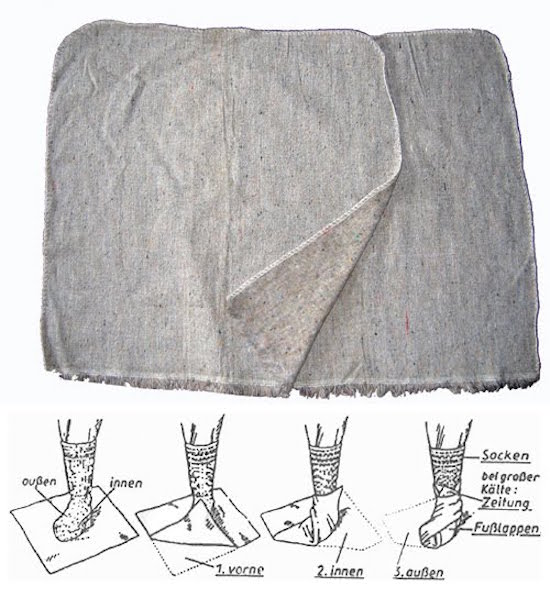

Being easier, we will begin with the Fußlappen. I own a surplus pair made in East Germany (the Germans carried the style forward from the Prussian era until 1960). They are squares of a sort of flannel material, 18 inches to the side, hemmed on three edges, with a burlap feel to one side and a softer nap on the other. I have no idea how they managed this, and finding out is not worth the trouble. They look like they're made out of scrap fibers - a generous way of saying they appear to be made of industrial dryer lint (what the hell, they're from East Germany). At the time of writing they are still available from a few surplus vendors; but while they're cheap, you've got better things to spend your money on.

Image and instructions from an East German manual

My own pair, next to my ski boots

If one were to make them out of scrounged materials, as when alone and in a bad way, perhaps the best materials would be wool or polyester fleece, with cotton flannel or "bed-linen" material being only suitable for summer wear. T-shirts won't do at all, nor will any other knitted material - woven, non-stretchy fabric is called for. For one thing, any stretchiness will allow creases and unwanted friction on the foot, a sure recipe for blisters. But more importantly, knitted things which aren't finished at the edges will rapidly unravel.

I consider 18" square to be nearly ideal for my feet; then again, I have small feet (you bozos in the back of the room can keep your jokes to yourselves). The best measurement, if you must fashion a pair for yourself, is the ancient "cubit;" that is, the length from your own elbow to the tip of your own middle finger. This measure will be roughly proportional to the length of your own foot - a rare occasion when anthropomorphic units of measure win out over more universal standards.

I gather they're supposed to be rotated to ensure even wear and longer life. I don't wear mine nearly often enough or long enough to induce real wear; though during one year's brutal winter I often wore them during the day in my work boots.

Everyone's foot is different. If my own experience is any guide, though, when worn correctly, Fußlappen ought to fit in your normal boots if worn without socks. They are bulkier than socks, especially above the "bridge" of the foot, and will not go much above the top of an ankle-high boot. Fußlappen - or indeed any wrap - when worn with socks call for a boot at least a size larger than when worn with only a single pair of socks. Bear this in mind if you're using them to supplement socks you're already wearing. If worn correctly, they provide a bit of additional arch support in boots which don't have much. Keep this too in mind and adjust accordingly if you have flat feet or if your boots already have inserts in them.

This is the process for putting on Fußlappen:

Start with your heel somewhat "aft" of the center of the rectangle

Leave "wiggle room"

Which side you start with is a matter of preference - just keep it tidy

Wrap the rear portion up and keep it gathered 'round your ankle as you put your boot on

I have in my possession a very brief treatise on guidelines for wearing the field uniform of the Red Army, written in Russian. In this treatise, the instructions for wearing portyanki take up as much space as any three other points combined - to include the wear of the helmet. It could be said that this is because the Red Army cared so much about its infantrymen and their comfort that they wanted to make sure they got the finer points across. It could also be that portyanki are arcane relics, retained for cost's sake alone, which take considerable trouble and practice to put on correctly.

There is truth to both. A blistered soldier is at best a nuisance (from the perspective of his chain of command). At worst he is an infected, immobile liability of no use to anyone including himself. In any case he is miserable, and no army in the world considers avoidable misery a necessary part of its training doctrine. What's more, Russia from time immemorial has always opted for the cheaper, more primitive, less elegant - if more complicated - option, especially as regards her soldiers. In addition to the instructions on wearing the portyanki, the treatise gives the Russian soldier cold weather tips - stuff your boots with newspapers, buy some insoles, rub goose grease (unsalted) on your feet, etc. - along with the usual advice on the fit of boots and shoes.

The principal trouble with portyanki is their learning curve. It is steep, certainly when compared against the absolute simplicity of wearing socks. Putting on portyanki takes practice of two types. The first is learning to put it on so it will stay on your foot long enough for you to get your boots on. The second is learning the various little adjustments necessary to keep them from torturing your foot from wrinkles or folds in the wrong places.

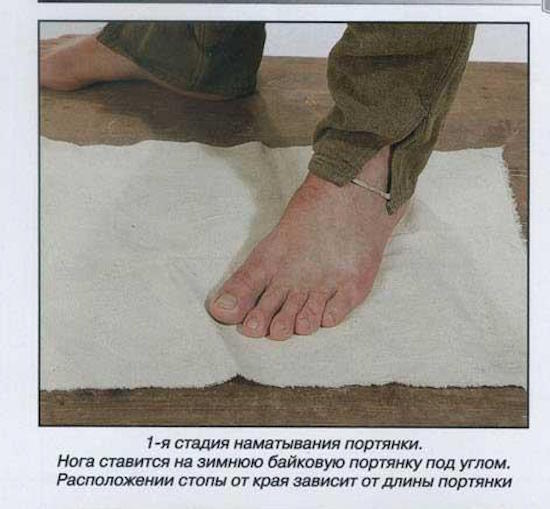

This is the best set of images I've seen for communicating the process of putting these things on. They appear to come from a 2007 (yes, that recently!) pictorial essay in a Russian NCO periodical. The italic text is my own translation - comments in brackets are my own additions where I consider them necessary:

Step 1.

The foot is shown on a winter weight footcloth at an angle. The position of the foot from the edge depends on the length of the footcloth

[In other words, you have to fiddle with it a bit in order to find out where your foot belongs on it]

Step 2.

The short part of the footcloth is pulled tightly around the corner.

If the width allows, it can cover the toes.

Step 3.

The corner of the short part is wrapped over and tucked under the foot without wrinkles and is held while pulling the long part.

Step 4.

The long side wraps tightly around the bottom of the foot and covers the instep and sole

[Some fiddling and adjusting of the back bits will be necessary at this point so as to avoid creases]

Step 5.

The back edge of the free part is wrapped around the lower leg over the front edge, which is not fixed.

[In other words, the corner you'd ordinarily think would wrap around the top is counterintuitively wrapped DOWN toward the foot, while the part you'd think would wrap down is now above it]

Step 6.

The end of the part wrapped around the lower leg is tucked under the winding so that the footcloth is tightly fixed.

[this is why you wrapped it counterintuitively]

See? Wasn't that easy?!

The procedure for the opposite foot is a mirror image of the first. The front bit is either tucked up under the toes "somehow" or just left stuffed in the front of the boot. I've watched far more youtube videos of Russian kids in camo and buzz-cuts putting these dumb things on than any well-adjusted American ought to, and not one of them seems to give a flying fig about this part. The front part is clearly not considered important.

In the interests of FNV I wore a pair of portyanki for an extended period (a few hours) a few days ago. If you can manage - after carefully studying the photos and translated text above - to make portyanki work for you, be my guest. I was able to make them work, but just barely and only after considerable fiddling. As for me, they lose over the Fußlappen in the criterion of ease-of-use. Fußlappen are relatively easy - portyanki are not.

About the only thing you can say in defense of portyanki is that they are versatile. The Russians, I gather, tended to make theirs of linen for summer wear and wool flannel for winter. Both are good materials to wear against the feet, though wool of varying weights is probably superior in the long run if you can get your hands on it. I made my portyanki out of a sort of woven cotton which doesn't stretch like knit material. Historically, the size was around 16" by 32" or so. Cut them a bit bigger than you think they should be - you can always trim them.

The peasant "onuchi" variation is the same width, at least twice as long and is wrapped higher up the leg, covering trousers or breeches - about as high as a gaiter or puttee. It is nowadays worn only with their "lapti" bast brogans and other traditional "peasant" wear (boyars and the middle class wore boots); the shoes and wraps are both held on with any of several types of cord, wrapped up the leg in a manner superficially similar to the ribbons holding up the leggings of Shaolin monks.

Of the few videos I've watched of people putting the Russian things on, most do it hurriedly and make a botched, somewhat slovenly job of it - photographs of 19th century Russian peasants wearing "onuchi" with bast shoes tend to have a much more workmanlike appearance, like the photo above and like the first photo under the title of this essay. Never having bothered with this variation, I can only speculate that it and the Romanian versions go higher up the leg for two reasons: warmth and economy. Warmth, in that it puts several layers of cloth around the lower leg; and economy, in that when the heel gets worn out, it can be trimmed and the cloth just not wrapped as high next time.

In the end, I cut up my portyanki material for other projects, one of which was a drawstring bag that holds all my skiing accessories, including the Fußlappen.

I have worn both types of footwraps long enough to consider myself qualified to pass judgment on them, which is to say not terribly long at all. I incline to the belief that if one is forced to make such a thing, the type and method adopted by the Germans is superior to that of the Russians on the sole criterion of simplicity - the Russian method is just too bothersome. If we're in such dire straits that we need to make these items in the first place, it means our lives are complicated enough without having to fuss over getting our feet wrapped up "just so."

In an article I haven't yet finished, I'm rather merciless in my disparagement of the "disaster blanket," particularly as relates to its durability. To do it justice, it's designed for short-term function as well as cheapness in mass production. Durability is NOT a design criterion, so it's uncharitable of me to expect it. But in regard to cutting the thing up for footwraps and otherwise insulating cold-weather footwear, the cheap disaster blanket is a commendable resource.

Disaster blankets are bulkier than wool blankets, with much space for insulating air. They are similar to wool felt; if you live in a cold climate and have many boots to insulate for a season, you could do worse than purchase a disaster blanket and cut it up to fashion insoles. Sew an edge around the outside if you want to be fancy, but remember the blankets themselves are disposable. The crafty Rubie may as easily fashion "bootie" inserts from disaster blankets, and I suppose those so made are less expensive than purpose-bought inserts, though they will fall apart quicker. In the line of "bootie inserts," the Russians offer us an example in their wool-felt "валенки" (pronounced "valenki"), worn with rubber overshoes when conditions are wet or muddy - which, since it's Russia, is all the time. They are the Russian answer to Eskimo mukluks. Finland has something similar, which stands to reason.

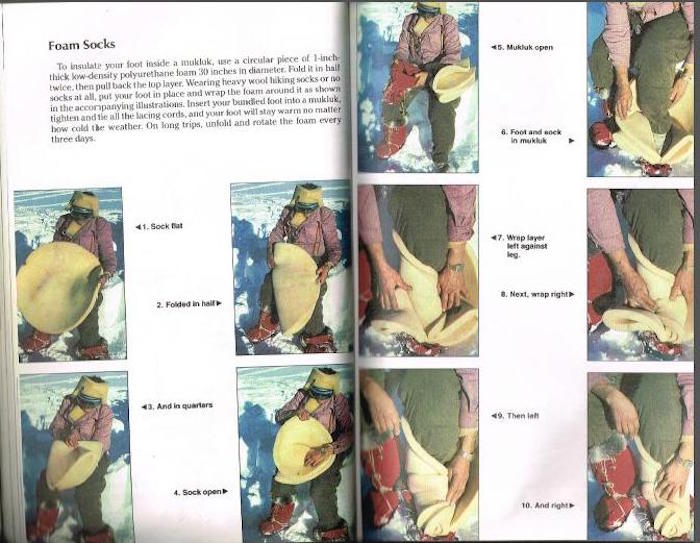

I bring all this up because there is a style of footwrap in the 1988 edition of the Boy Scout Fieldbook which lends itself very well to the use of cut-up disaster blankets. It was in fact my introduction to the idea of wrapping the feet to keep them warm in extreme cold weather.

The footwrap discussed in the book is made with 1" thick low-density foam padding, the sort used for upholstery. It is intended to serve as the bulk and insulation of a home-made arctic mukluk. It is one of several items in the Fieldbook made with upholstery foam, all of which straddle the line between resourceful, clever frugality and risible, senseless time-wasting.

I really shouldn't be so harsh. The inventor is, after all, coming at the issue from the context of outfitting boys for winter camping on the cheap, and inspiring their ingenuity and resourcefulness. Our context is as completely unlike his as it is possible to be, while still addressing the same fundamental problem.

I take the liberty of including the images from the Boy Scout Fieldbook below, as they are illustrative of the concept:

Do like this, only with a circular piece of disaster blanket

The folding method above has the advantage of placing several layers of insulating material UNDER the foot, which portyanki and Fußlappen don't do.

Of the materials evaluated for fashioning portyanki or Fußlappen, the disaster blanket is a poor choice - it is too bulky and not strong enough. Per contra, it is nearly ideal when made and folded after the fashion of the "foam sock" above, though the boots must be cut much larger than normal - galoshes of the old-fashioned metal-clip variety recommend themselves, as do the green Army "wet-weather" overboots.

Knowing how to fabricate a replacement for worn-out or absent socks is undeniably low on the list of preparedness skills to learn. As I said in my introduction, there is no good reason to lay in a supply greater than that needed simply to learn the procedure. But one of the advantages of learning skills versus acquiring items is unarguable: unlike any item which ultimately will wear down, break or go missing, a skill once learned to proficiency never truly goes away.

This website has a very good tutorial on putting on portyanki. Scroll down to about halfway and you'll find not only the clear instructions but also the fact that the ones the author uses to portray the concept are scandalously filthy (he must be the guy who brings the lice to his re-enactments).

GVI

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2021 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.