Themis has one kind of ancient scale - we're talking about another...

*The Steelyard*

Themis has one kind of ancient scale - we're talking about another...

This article will be an introduction to one class of tool we may seldom need but when we do need it, there is no such thing as a meaningful alternative, and that is a scale.

Most people have a bathroom scale and many will have a small kitchen scale. Reloaders may have minutely precise balances or digital scales for the small amounts of propellant needed for cartridges. Postal scales are of nearly infinite variety - I have a couple of the older pendulum arm type that could be kept in a clerk's pocket or desk drawer. They're not terribly accurate, but they're close enough for knowing how much postage to affix to an envelope. My kitchen scale conveniently allows for "tare" weight, or the weight of the container holding whatever I want to weigh.

These need no further explanation

One ancient type of scale that passes what I call the D.I.R.T. Test (for "Durable, Independent, Replicable and Transparent") is the steelyard scale, also simply known as a steelyard, which is what we'll be calling it throughout this article. Wikipedia has a decent writeup on their principle, history and other trivia not worth repeating here. This essay will limit itself to a discussion of the two "store-bought" examples in my possession. An update (perhaps a "volume 2" - haven't made up my mind) will go into how to make one for ourselves, as well as why we might want to do so.

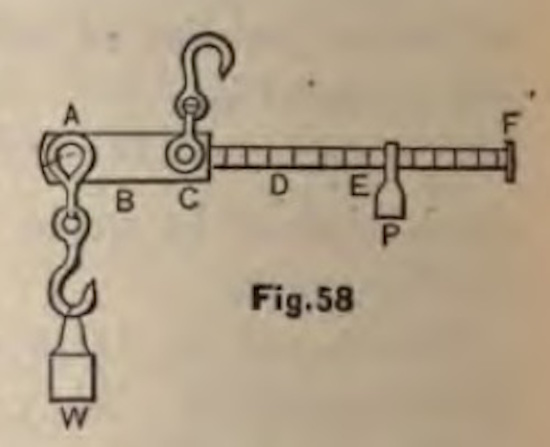

Diagram in an old textbook on mechanics

Steelyards are a type of unequal balance where, instead of two pans on a beam (the thing you see Themis or "Blind Justice" holding in her non-sword-wielding hand), it has a weight called a counterpoise (P in the diagram) on a graduated rod at one end and either a hook or a pan (W) on the other, and moreover the entire thing hangs off-center. There are two principal types of steelyards; you'll find them under different names but because it's my article and I can do what I want, I'm calling them the "common" and the "Scandinavian" - you may also see a version of the latter referred to as a "bismar" scale. Since, like, forever, "common" steelyards have had two or more "ranges," made by having more than one balance point on them. This enables the scale to measure smaller weights more precisely, or greater weights to a reasonable degree of precision. The "Scandinavian" and "bismar" steelyards have a fixed counterpoise on the opposite end of the bar from the one that has the pan - the weight of the pan is determined by locating the point where the bar hangs at equilibrium. Mechanically it's simpler but it has limitations which render it less capable than its more complicated cousin. And again - since it's my article and I can do whatever I want - we won't be discussing it further. You can find information about it at the Wikipedia link above.

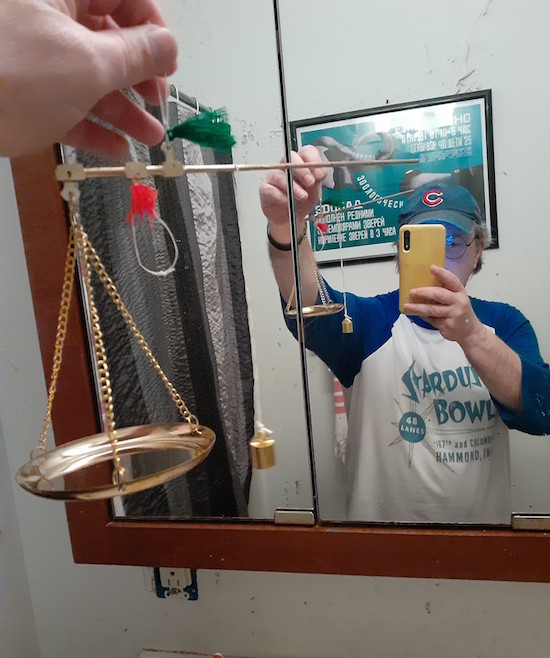

The two steelyards I own

Kind of impressed that it takes only two of these things to cover such a range of weight.

I own two "store-bought" steelyards. The first one was claimed by the vendor to be surplus from France. It has two "ranges," the first going from 0-to-11kg in 0.1kg increments, and the second from 11-to-50kg with graduations for every kilogram. For Yanks who insist on non-metric units, it will weigh from 0-110 pounds. Aside from a stamp indicating its capacity, it has two "maker's mark" type stamps on it - a three-leaf clover and something that looks for all the world like the human brain but almost certainly isn't - God only knows what it really is. Since I don't know anything about these maker's marks, I have no firm idea whence it comes, but it really doesn't matter. Steelyards this size are presently easy to find on eBay and at the time of writing, the prices aren't unreasonable.

Seen here weighing a piece of lead

Recently I acquired a small steelyard from China, also off eBay. It's not an antique - it's new-made. Since I'm using it in making up Traditional Chinese Medicine "Witch Doctor" preparations, I feel no particular obligation to confine myself to domestic industry. Being MUCH smaller, it of course measures much smaller weights, yet more precisely; and having a pan instead of a hook gives a hint not only of its capacity but also the nature of the things intended to be weighed in it (handfuls of herbs, precious metals and so on). Like its big brother, it has two ranges: 0-30g to the half-gram and 30-100g to the full gram - I'm not going to bother converting this for Americans. The counterpoise weighs 16 grams.

I was pleasantly surprised by its accuracy. I have a set of calibrated metric weights and, when the device arrived, the first thing I did on unpacking it was test it out. It turns out to be accurate to within much less than 1/2 of the smallest graduation. The smallest graduation is 0.5g; therefore, it's accurate to +/- 0.2g. I'm quite pleased - it's not merely a "decorative" item, despite being shiny varnished brass - it's also a useful measuring instrument.

In short, these two scales can weigh everything from feathers to 5th graders.

You may have noticed that the Lee Powder Scale in the second photo is itself a variation of the steelyard principle, being an "unequal balance" scale. The old "DETECTO" scales you may remember from the doctor's office were also technically steelyards. Mankind is a vastly inventive and imaginative animal, once he gets a principle in his head.

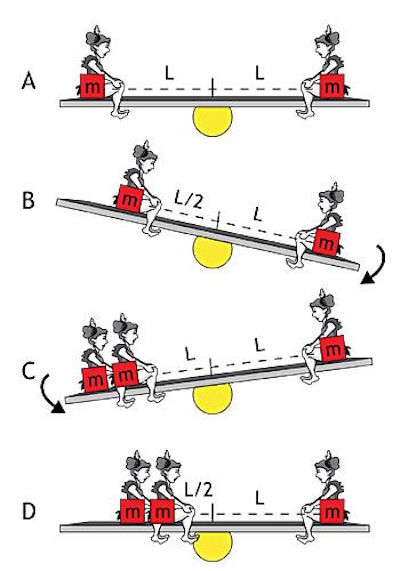

The physics involved in how steelyards work is identical to how a see-saw works or rather, how they ought to work if the kids play nice together.

I could go into detail but I don't think I need to. The steelyard is in a class of artifact that satisfies the "D.I.R.T. test" criterion of being "Transparent;" that is, someone of average intelligence can figure out how it works just by looking at it hard enough or playing around with it long enough. I know this because the "French" steelyard came with no instructions whatsoever, and the small Chinese one came with - you guessed it - an instruction leaflet printed in Chinese, and my comprehension of written Chinese at the time of writing is nowhere near what it needs to be in order to make out what the leaflet says.

The smaller one has a pan but, as you can see, the larger one has a hook. Most steelyards this big have only a hook, and it's up to the user to figure out how to adapt it or the load so as to enable the scale to weigh it. If the item to be weighed has a means to be suspended by the hook, so much the better.

Believe it or not, this pail is part of my workout gear

What you see is of course a sort of stockpot with a lid, being weighed by the large steelyard. The "lower weight range" is selected by suspending the steelyard from the ring nearest the hook.

When you're keen to quantify your misery.

For the record, this backpack as presently loaded is 10.9kg or just proud of 24lb.

Some awkward weights must be put in something, and then that something itself weighed to account for the "tare" or "weight of the container, to be deducted from the gross weight." There's no way to "zero out" a steelyard like there is with more modern scales; however, if the "container" (usu. the pan in a small steelyard) is permanently attached and therefore constant, this weight can be accounted for.

This section addresses the "D" section of the "D.I.R.T. test" - its "durability." "Durability" doesn't just refer to whether the thing is indestructible or fragile. It also refers to whether the artifact is still relevant. For example, common claw hammers are physically durable and still entirely relevant. Rotary-dial phones, on the other hand, while being very practically indestructible are obsolete in the modern phone network. Wine glasses, while fragile, are of course relevant, whereas computer punch-cards are both fragile and obsolete.

A steelyard is relevant in that things will always need to be weighed.

You have an imagination. Use it.

In a preparedness context, we may not have power for large scales such as those I used to use in an Army Post Office in Iraq, nor access to the kinds of batteries that power my tiny digital reloading scale. Speaking of reloading scales...remember that nice red Lee scale in an earlier photo? While it too is a type of steelyard, both accurate and precise, it's not the sort of thing I can take out to "the field" or to market. It must stay on a level and reasonably hard surface such as a table or workbench, and its razor-edge pivot does not admit of rough handling. My small steelyard isn't bombproof, but I can put it in a small pouch or box and so long as I didn't run an obstacle course, it'll be none the worse for wear when I get wherever I'm going.

In a way, we've also satisfied the "I" portion of the "D.I.R.T. test" - that of "Independence." Spring bathroom scales are pretty independent - they take neither batteries nor house current and need no infrastructure in use. But springs wear out over time and spring scales are not terribly portable, nor very accurate; good enough for baking (or, at the other end, indicating that you need to cut down on the baked goods), and they need a flat surface. Laboratory "gravimetric" scales are incredibly precise - even those that use mechanical means to measure. But they aren't for everyday use; they must be kept under ideal conditions, and they must be made - and calibrated - by specialized machinery or trained technicians at companies that may no longer exist in a "Prepper Paradise."

Steelyards aren't as convenient as spring scales, nor as precise as laboratory scales. On the other hand, they are accurate enough for "Prepper-Land;" you can hang them from any convenient hook, beam or branch, or just hold them; they require no calibration once made and - this is the important part - you can make them.

In the future, I intend to make two steelyards of my own, small and large, in parts of an ounce all the way up to 100 pounds, updating this article once complete. One of the problems of "lifestyle preparedness" is that of having too many projects in queue, and this project is in no way immune to it. I mean to do this for two reasons: first, to prove that I can - and, therefore, so can you. Second, to satisfy the last element of the D.I.R.T. test - that of "Replicability."

GVI

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2025 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.