Rita Mae Brown is someone worth listening to

*How to Evaluate a Tool's Quality*

By: GVI

30 March 2023

This essay will lay out my system of evaluating tools of almost any kind, using the example of a set of saws that feature in a companion article. In other words, I show the method by which I determine whether the saws in the collection are fit or unfit for their intended purpose, and discuss the general principles of this method in order to apply them to anything from woodworking tools to auto maintenance tools to kitchen gadgets/appliances or indeed whatever sort of artifact or product you please.

This method comes with a few strings attached. The biggest, knottiest string is the fact that in order to evaluate a tool against its companions, we have to have a reasonable base of knowledge to call upon. If I don't know what a tool does, how it works, how long it's supposed to last or how to maintain it, I'm basically stuck reading amazon reviews or vendors' ad copy and taking them all at their word until I get this base of knowledge. I'm sure every reader can recall a purchase he or she made in innocent ignorance, only to find, after experience with the item, that they'd wasted their money.

Rita Mae Brown is someone worth listening to

That's the second string. "Poorer but wiser" was an ancient concept back when Solomon wrote the Book of Proverbs. How to acquire this base of knowledge - whether by book learning, tutorial video, practice with a knowledgeable friend, non-credit college courses or (my method) regularly screwing up, wasting time & money and hopefully learning from one's mistakes - is a worthwhile topic all on its own, but it's also beyond the scope of this essay. The saws shown here fall in the "poorer-but-wiser" category, because I spent my own money on everything here, and it was only by holding everything up to its companions that I was able to come to the conclusions I did. But such expense is not always necessary.

There are many different ways to evaluate a tool's fitness for purpose. Mine is straightforward and works for just about any common artifact:

I used the weasel-word "common artifact" because there are exceptions, as in the case where a tool's function is so unique (for example, the headspace gauge for an M2HB machine gun) that no meaningful competition exists. Same goes for "field-expedients" made at the time of need. We're not talking about these things, so please be so kind as to keep the "But-What-About..." to yourselves.

What follows is the practical application of the above questions to a set of three hand saws. They're called "back saws" in the United States and "tenon saws" in the U.K. but there's plenty of overlap - you'll hear Yanks and Brits use both terms interchangeably. This class of saw has the following features:

Larger "panel" or "carpenter" saws - the ones we all have in our garages - are for cutting stock to rough size, with the intention that they be shaped to final fit with other tools. Back/tenon saws are for making precise cuts in dead-straight lines which need little or no further finishing (e.g. chiseling or planing). They're for things like cutting tenons, mitered angles, lap joints and so on. They're often used with a miter box or a bench hook for extreme precision; their cuts are cleaner, with less tear-out, and the "kerf" - the width of the cut - is narrower than that of a panel saw. Smaller "carcass/carcase," "dovetail," "flush-cut" and "Gent's" saws also have a thin blade and reinforced back, but they're smaller and meant for more delicate work. Tenon/back saws can do this - they're a general-purpose saw - but being the largest of the saws with a reinforced back, they're optimized for bigger work.

Typical panel saw (above) and back saw

(author's collection)

Flush-cut (left) and "Gent's" saws

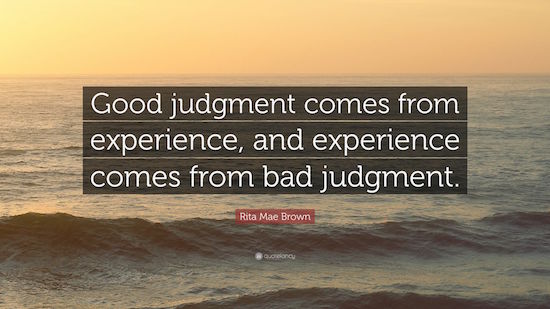

Not long ago I took a trip to Ohio; and one of the places I made sure to visit was a business in Amish country, just outside Millersburg, southwest of Canton. It goes by the name of "Colonial Homestead" and its proprietor is an Amishman who sells antique hand tools, blacksmithing equipment (e.g. anvils from toolbox-sized to Wile E. Coyote sized), a trifling amount of blackpowder gun tools and a few flintlocks/caplocks. He also holds classes and does gunsmithing and his own furniture work to order. In short, he's an unquestioned Subject-Matter-Expert. I spent a good while in conversation with him during my visit. He's about 20 years younger than me but carries himself with the quiet confidence of someone you spend more time listening to than talking to. He's also, like most Amish, a savvy businessman. You could learn a lot from him and it's worth the trip to go there.

No online presence and it's anyone's guess whether the phone gets answered when you call.

They don't take credit cards - cash, check or money order, and the nearest ATM is 3.5 miles away.

Remember - AMISH.

You will not find the "Deal of the Decade" there, and you shouldn't expect to. This isn't just any old antique mall - the owner charges a fair price for everything he sells. The purchase comes with his own expertise, which you'd be wise to ask of him, even if (especially if) you think you know what you're doing. It's been my experience that it's almost always worth the extra cost to purchase from someone who knows what he's talking about than it is to try and roll the dice with someone like a yard-sale seller or an auction house worker who has no idea what either of you are looking at. For one thing, you usually get the seller's expertise at no additional charge; but more importantly, you're keeping this expert in business.

So give people like the owner of "Colonial Homestead" your business and make sure you pick their brains clean when you do. If I'd had the benefit of such an expert about 20 years ago (and if I'd had the wit to listen to such an expert), I wouldn't have the experience or the artifacts that make up the rest of this essay. But I was pigheaded; and now that I know better, I'm obliged to share the lessons driven home by this pigheadedness.

While at "Colonial Homestead," I spent a great deal of money on a number of tools:

I'm old enough to have nice things

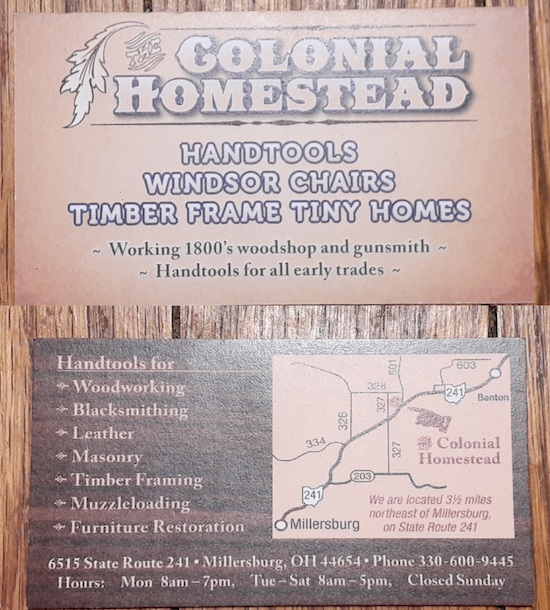

A good rule of thumb to follow is that it's almost always worth the trouble and cost to spend extra money on something when you know for a fact it's the last one you'll ever have to buy in your lifetime. The "Vimes Boots' Theory of Economic Unfairness" usually applies:

We all know it, but it's rare to see it said out loud.

Exceptions abound. For example, I regularly get ads on Facebook for pencil sharpeners. I don't know why so don't ask. These sharpeners range from the simple to the ridiculous. A few months ago someone tried to sell me a gold-plated mechanical doohickey that promised "The Ultimate Pencil Sharpening Experience." It cost a couple Benjies.

"The Ultimate Pencil Sharpening Experience."

Full Disclosure: I didn't buy it.

The box in my dining room where I keep my writing utensils has a pencil sharpener of the dinky aluminum "bog-standard" sort that are about the same size as the dice you get with a board game. It probably cost me $1.49 or so and it will outlive me. It's probably safe to say that the $200 one pictured above will not sharpen my pencils 133.3 times better than the one in my "escritoire," and that the only real purpose to owning such a silly tchotchke is to be seen to own it. We seldom give much thought to the degree to which the world's economy relies on those with more money than sense.

I bring this up to establish the fact - which shouldn't need to be established - that many times, extra cost does not automatically translate to extra value. We all know this too. Above a certain price point, most things are usually "good enough" for most people. The egghead term for this is the "Point of Diminishing Returns." We'll revisit this concept again later in the essay.

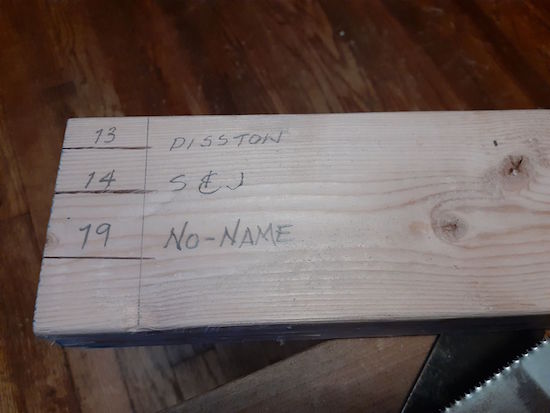

From top to bottom:

This is how they measure out:

DISSTON:

SPEAR & JACKSON:

NO-NAME:

* The "set" of the No-Name is kind of misleading. At 0.002", or 0.001" each side, it can hardly be said to exist. The plate is in fact wavy in the same way as a hacksaw blade, which is so shaped in order to prevent it from binding in a metal cut - a perfectly flat hacksaw blade would get stuck in the cut. No-Name is wavy for the same reason - we'll come back to this arrangement presently...

I didn't measure the length of the saws or the "Depth of Cut" because the difference in real terms is relatively meaningless.

Let's now answer each of the evaluating questions I listed earlier:

I know this last part because the tooth and plate profile it presently has is not at all original to it - it was ground flat at some point, then tapered; the teeth were re-cut (they originally came from the factory with 12 or 14 teeth to the inch, not 13 as it currently has), sharpened and re-set in the manner described above, which are all things Disston never did.

Well, this antique Disston obviously meets this standard, as do many other antiques at this price point. Remember my antique was rehabilitated by an expert for the express purpose of putting it back into service - we should expect to pay a premium for this sort of work. In terms of new-made tools, Lee Valley/Veritas and Garrett Wade make examples that are in the same class and about the same price ($145 and $155 respectively). Crown Hand Tools of Sheffield makes one for about $100. These are all made of roughly the same materials (some use brass in the back rather than steel but this is an immaterial difference), the handles are well-made from good woods in the classic style. The exception is Veritas - it uses modern composite materials for its handle & back but is otherwise the same thing. And while I don't own them, I've watched videos of woodworkers I trust using each of these tools. The videos indicate that these tools perform similarly to my Disston in terms of cut, and none of the woodworkers complained of binding or difficulty in starting the cut.

Moving afield of the realm of saws, "standard" applied elsewhere might find meaningful examples in such things as

This question is applicable to more tools than just saws. In general terms, you're looking at materials, workmanship and performance. As applies to this class of saws, it's best to go straight to the questions that follow this one. Moving away from saws, think about the above and also think of durability. Some things are made to last a lifetime; others (even in "top-tier") are disposable. The world's best respirator filter, for example, is still meant to be thrown away once its useful service life is up.

Next-Tier-Up for these types of saws would be antiques in unused condition, and new-made saws that have either exotic materials or are made-to-order. They all start at the $200+ range and go up to "If You Have To Ask, You Can't Afford It." An unused antique is a collector's item - not a "user" - and as such, using it will spoil its investment value. To one who wants to use the tool, this is like having no tool at all, for they don't appreciate in value so quickly that "flipping" them is a reasonable investment. An example of a new made "next-tier" tenon/back saw would be Lie-Nielsen's. It has a cherry handle, is rather large (16"), and sells for $250-$275 at the time of writing. I'm acquainted with a few saw makers and their tenon saws all start around $275, with saws being made-to-order naturally costing more.

They are all unquestionably well-made and built to last several lifetimes if cared for. But they don't do anything better than the "standard-tier" saw will, and "standard-tier" saws will last just as long (or rust to junk just as quickly) as their more expensive companions. They generally have the same number of teeth per inch; if a user gets a Next-Tier-Up saw and wants it to cut more aggressively or cut a finer kerf, he'll almost always have to do the work on the saw himself or pay to have it done. Not only does this introduce its own problems, it's also the same way you get the same differences out of a "standard-tier" saw. The extra cost is not related meaningfully to performance or durability.

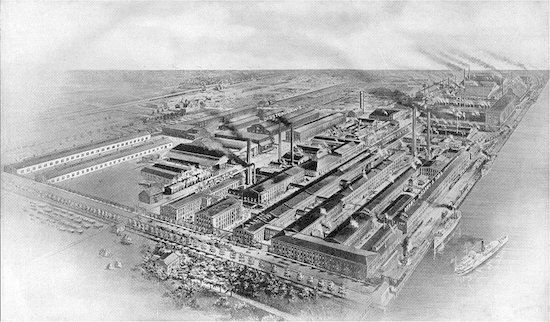

One custom maker in particular makes a big deal of his pride of workmanship. He is unquestionably proud of the work he does, and you can't blame him - his saws are beautiful and well-made. He also makes a big deal of the fact that his tools are made in the United States by a small-scale made-to-order craftsman. I talked about giving our business to "experts" before, so it would be hypocritical of me to say that his expertise is not worth paying for. But I will be a bit cold and calculating in his other selling points. His pride of workmanship does not make his saws cut better - his expertise does. The point-of-origin does not make the saw cut better. Even if I knew where the steel for his saw plates came from, the place of their manufacture, to me, is meaningless - I'll take a saw from Derka-Derkastan if it can be proved to do the job well. As for the small-scale craftsman, it too is an intangible that doesn't inherently contribute to the quality of the tool. The antique Disston saws every collector wants and every woodworker fawns over are Industrial-Age tools that were made in a large factory in Philadelphia, complete with its own foundry.

The Henry Disston & Sons factory, ca 1910

I'm not the man to say you shouldn't take this craftsman's sales pitch into account. I'm also not the one to say you shouldn't buy a high-end tool when a "standard-tier" tool will do the same job as well. We just need to be aware that above a certain price-point, you're often looking less at performance or durability, and more at intangibles.

This is far from a universal statement. Many tools and artifacts in "Next-Tier-Up" are a real improvement, provided we need this degree of improvement. A Winchester Model 70 might serve the needs of 90 percent. of big-game hunters, police department snipers and (for a long time) the U.S. Army and Marine Corps. But for the 10 percent. who need better, no amount of money is too much go get exactly what they require. A majority of the "Super-Duty" pickup trucks in the Home Depot parking lot never leave the pavement; but at least one-in-ten (usually the ones with a ladder rack that need a good wash) are essential to the owner's livelihood. In my own profession, a surveying instrument that's accurate to 10 arc-seconds is sufficient for 90% of paying work. But for the times we realistically need more precise and accurate measurement, the extra expense of a 0.2 arc-second instrument is entirely justified and reasonable, as is the extra training and finicky technique to make use of such an instrument. For specialized tools like these, a realistic assessment of our own needs is the best guide. In other words - especially in a preparedness context - unless I know for certain that I need something specialized or high-end, the odds are very good that I don't need it, and any extra money or trouble I expend on such an item will probably be wasted.

Having established my Disston as "standard," and having established that "Next-Tier-Up" doesn't give me any benefit that's worth the cost (at least when it comes to back saws), what does "Next-Tier-Down" look like? In my case, it's represented by a Spear & Jackson back saw that just arrived and which I go into at greater length in the companion to this article.

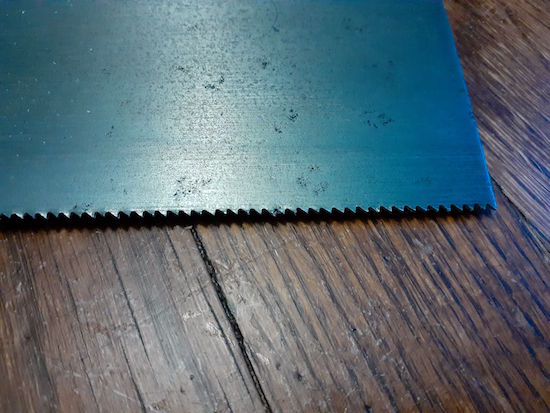

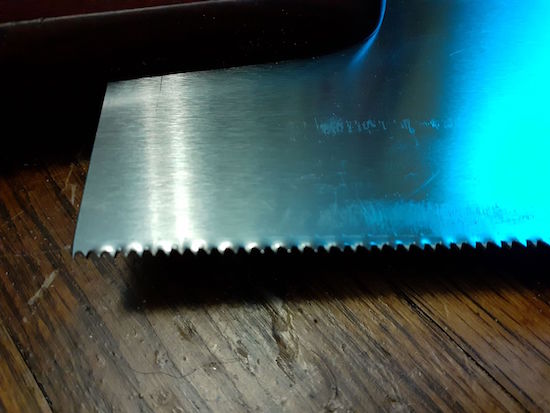

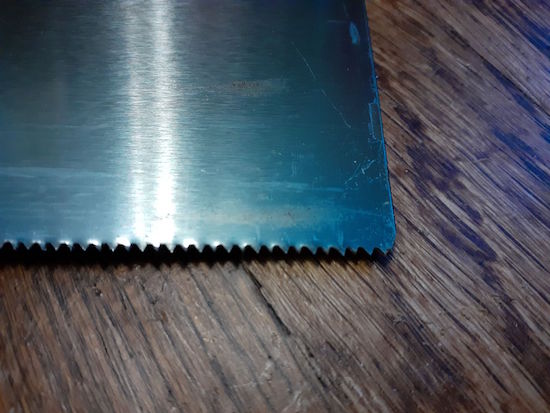

Hang on to this photo in your mind's eye for a moment...

As you can see, it makes a nice clean cut, with about the same effort as the Disston. This is after I'd put in about a half-hour's work on the teeth - it didn't do nearly so well when I first pulled it out of its cardboard sleeve. The plate has a sort of lacquer that I haven't yet taken off and which looks to need acetone or something like that (which I'm low on); but once I take it off and wipe it down with beeswax - something every saw benefits from - I expect this saw to behave just as nicely as its older brother. The handle needs re-shaped but while it's ugly, it's still comfortable enough that I could just leave it alone if I wanted. Lastly, the "brushed" finish on the brass back and the plate look like they were achieved by holding the thing up to a bronze-bristle wheel on a bench grinder. It's a bit of an eyesore, but it was something done to keep the saw to a reasonable price point - the simple act of polishing and buffing the brass would have easily added $10 to the cost, and a buffed brass back does nothing for the function or durability of the tool.

Antiques that are in good condition but need restorative work - such as removing surface rust/dirt, sharpening/profiling of the teeth and so on also fall into this category. They are the ones you will find most reliably on eBay or Etsy for between $30-$100 or so. Anything costing less than this from someone who knows what he's talking about is liable to be more effort than it's worth and may well be unusable junk; anything more expensive ought to have been restored by the seller.

Apart from saws, "Next-Tier-Down" in other areas include:

Refer back to the photo of the three saws' cuts. You'll clearly note that the one from the "no-name" saw is the thinnest and cleanest. Thin and clean it is, but you'll also note it's nothing close to square to the line of the wood. This was not operator error. The other two saws made their cuts with no problem, and it's relatively easy to make a cut within a few degrees of square with a decent saw. But the no-name saw simply will not track a line on its own and never has done, for as long as I've owned it. It's almost as if it has a mind of its own; specifically, a willful mind filled with spite and contempt. And here's another thing about that thin kerf. It's so thin that even after such a short cut the plate starts binding in the cut and I have to force the thing through the cut - the last few strokes on the cut in the photo were much harder than they should be, and they extend beyond the "goal line" not because I kept going, but because I had to change the angle of the cut to get that far. The only way I could ever make it cut square was to hold a metal set-square up against the plate and use its tendency to skew off-line against it; in other words, I'd have this saw trying to saw itself into a set-square's steel arm in order to get it to cut square. Not only does this ruin the tiny teeth; it also tends to take out the waviness that passed itself off as this saw's "set," which of course only made it bind worse. Combine this thinness of cut with its tendency to wander off-line and the tool becomes useless.

It looks rusted-out and crummy, but this was owner (me) neglect, and didn't make the saw any worse than it already was. More important was the teeth. It's pretty much impossible to sharpen a saw with 20 teeth to the inch. It's definitely impossible to give it a proper set, which is why it has that waviness. This was introduced by a machine at the factory; it can't realistically be done by the end -user and for a saw of this type, it shouldn't have to be. This was, in fact, not a tenon saw or even a miter-box saw. It was a fat hacksaw with a spine, and about as much use.

I didn't really want to write this essay when I did. However, once I had two proper back saws, I wanted nothing more to do with this useless tool that's really only plagued and vexed me for nearly 20 years. Genuine ignorance that there was any such thing as a better back saw is what kept me holding on to this hateful artifact so long. In fact, I'd go so far as to say that it - or rather, reluctance to do anything that required its use - kept me from doing many things that would have made me a better woodworker by this time. So eager was I to relieve myself of this unhappy thing that I had to hurry up with the measurements, test-cuts and photos before I sent it off to Goodwill. I dropped it off yesterday afternoon and I will never miss it. I almost have a conscience about giving it to someone else but who knows - maybe the new owner will do the smart thing and cut the saw's plate up to make nice panel gauges or something.

All this is to tell you that when you go to a Big-Box hardware store, see a $20 "Miter Box And Saw" on the bottom shelf and start wondering whether you should buy it, ask yourself if you'd purposely pay money for someone to give you a toothache. If you would, then pick it up because it's about as much use to you. If you wouldn't pay someone to give you a toothache - if you think even the idea of paying someone to give you a toothache is unthinkably stupid - then don't get this saw or anything like it because, just like the other guy, it will be about as much use to you.

In a preparedness context, "Unfit for Purpose" elsewhere includes:

It would be a mistake to think this essay is primarily about saws. It was originally titled "Three Saws - a Study in Quality," but I changed the title so as not to bury the lede. I've written several articles about woodworking tools already. Between them, the prepper new to Cheerios-and-coffee-powered-tools should have a decent start, at least so far as knowing where to begin looking to find the answers to the questions I never addressed.

Related to the "But What About" issue early in the essay, I'm bound to get feedback to the effect of "But have you tried Japanese saws? Why not?! Why do you hate the Japanese, huh?! How can you write about saws without saying a peep about ichiban Japanese ryobi and dozuki, you disgusting, bigoted gaijin?!!!!!11!1!!!!"

To those inclined to offer such feedback, I have this to say:

Again, this is not about saws or which saw is best. This is about a method of evaluating different artifacts within a given category: saws (Western or Japanese), kitchen knives, multitools, knitting needles, hedge trimmers...it doesn't really matter. As for Japanese woodworking tools, I know enough about them to know that when I started getting serious about woodwork, I had a choice to make - Western or Japanese. I chose Western; not only in tools, but I also chose to work exclusively in Imperial units. This is not to say that Japanese tools or metric measurements are inferior - they are not. They are simply different; and they're different enough that it's needlessly difficult to try to mix-and-match them hodge-podge. That's how you get billion-dollar explorer robots slamming into the surface of Mars, rather than landing gently like they're supposed to. I'm not building Martian explorers, but I also don't need to make my work more prone to screw-ups than it already is.

It's also important to keep these comparisons reasonable. Related to the saws at the center of this essay, it's foolish to compare a back saw to a panel saw. They're for different things. Likewise, it's foolish to compare a sports car to an SUV, or a microwave to a charcoal grill or a brand of toilet paper to a bidet. Compare like-with-like as much as possible.

Use your own native creativity and adapt this method to whatever tool or prep item you please. It will allow you to make wiser choices and avoid relying on amazon reviews.

GVI

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2023 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.