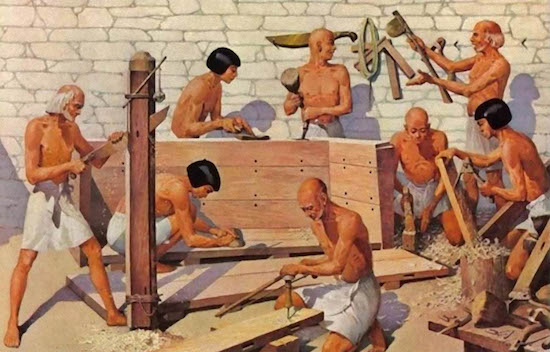

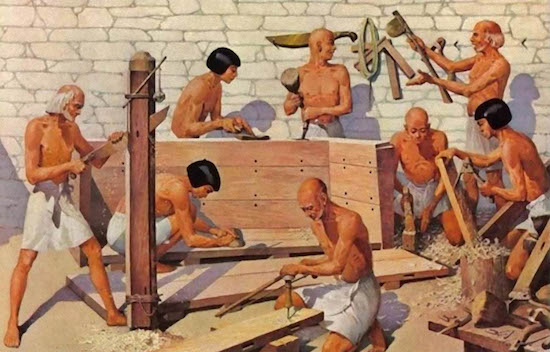

Okay, maybe not quite this primitive...

*Woodworking Tools - a Rubie Luddite's Approach*

By: GVI

30 December 2022

Okay, maybe not quite this primitive...

Between 2001 and 2008 I lived in an older apartment building in My Fair City. It was built in 1908. Electricity came to My Fair City in 1921. The building was retrofitted and for most of my residency there, this retrofit was in the form of 15-amp service with a fusebox.

This otherwise useless tidbit was my introduction to "breakfast-powered" hand tools. I had an electric drill and a circular saw, but every time I pressed the trigger on either, a fuse would blow, and it didn't matter which circuit in the apartment I attempted. But I still wanted and needed to make things, particularly out of wood. So I began to collect tools that were powered by the oatmeal and coffee I'd had that morning.

It isn't hard to make a preparedness case for tools that don't run on electricity. What's harder to do is make a case for learning how to use them well. They take practice - they're not "plug-and-play" devices. As one elder-statesman Rubie is fond of saying in a somewhat different context, "If you're not using it now, you won't be using it then." Speaking of context, I recognize that hand tools don't need to be used in every disaster the same way toilet paper, staple foods and soap do. As I type, Buffalo, N.Y. is under very sensible travel restrictions due to a severe blizzard. I'd be hard-pressed to say anyone in Buffalo needs a jack plane or a nail set for his or her survival right now.

But as I'm fond of saying in nearly every preparedness context, "We prep for the things we can't predict." I may have to repair a collapsed porch or re-frame a door. Or I may need to do some ordinary bit of work that I'd normally just throw money at, but there's no contractor available to do it, or no power for him to use his electric tools.

There are many resources now for the interested lay-person to set about learning how to use hand-powered tools. There are at least as many now as there were in the distant past; and I'd go so far as to say there are more now than there were a decade or two ago. Hand tool woodwork appears to have undergone a small revival of sorts in the last few years. I'm no sociologist; so I won't hazard a guess as to why this is so. I simply note that it is so, and point the aspiring learner toward this wealth of information.

The remainder of this essay is a collection and adaptation of several comments related to hand-powered tools on the Rubicon's "Community Center" forum. Between these comments and my added remarks, I mean to lay out why I went about tool selection the way I did and what advantages or disadvantages there are to my approach, as well as those of others.

The topic came up in the first place because I had recently undertaken a project of transforming one of the bedrooms in my home into a work room for woodworking, in addition to other work such as leather craft, sewing, reloading, fletching (making arrows) and so on. The transformation having been just been completed, I've set about the last few weeks filling out my small-but-full set of hand tools for woodworking - my collections of tools and materials for all the other activities above are already fundamentally complete.

The available space really limits what I can have, and I kind of like it that way. Not counting the small closet, the room is 9'x15'. That's not a lot of room, and I have to be smart about filling it up so as to keep the space usable and not cluttered.

Just big enough, but no bigger

It's like backpacks. I always used a Medium ALICE pack in the Army, even though I could afford a used Large one of my own, and the reason is because I never wanted to carry a full one (no one ever partially fills a big backpack). The small space forces me to be choosy and judicious in what I put here.

Then there's the aesthetic of minimalism itself. This is separate from "miniature." It's been years since I discovered that "mini-anything" is always less useful, often useless, and typically "gimmicky." But having exactly and only what I need, arranged efficiently and maintained carefully, has an appeal apart from (and in my opinion superior to) miniaturizing.

A sort of "Platonic Ideal"

Say what you like about the Japanese - there's no question Japan knows how to compress the maximum utility into the smallest possible space. If you can believe it, the setup you see above constitutes the entire apparatus of a traditional Japanese woodworker, and everything is full-size & intended for someone doing paying work. I can appreciate its appeal, but it's also too small for me - certainly too small to do the sort of furniture I really want for my home and in the future. Perhaps if I decided to start volunteering with my friend at church who runs the Habitat for Humanity branch in My Fair City, it'd make a good "itinerant craftsman" kit.

That's enough background. Let's talk about hand tools and where to get them.

When it comes to acquiring hand tools, there are four main approaches:

I leave out a fifth category - that of getting tools from older relatives - because the time when we had relatives with hand tools worthy of passing down is mostly behind us. It can no longer be relied upon. My stepfather, for example, passed on to his Eternal Reward at the age of 93 earlier this year, and he didn't have any hand-powered tools worth keeping - not only now, but at any time in his adult life. He worked as a watch parts distributor; what few tools he had around the house were for simple home repairs and were of the chintzy, department-store kind you'd expect maybe two or three uses from before they were unfit. I'm sure many of our elders are the same.

I also leave out the category of purchasing tools from collectors or those vendors who cater to them. In most cases, collectors are looking for rarity and distinctiveness, and these criteria tend to command prices for tools out of proportion to their utility. For one thing, a tool might be collectible because it was highly specialized and very few ever needed it. It could also be rare because it was a poor seller; and poor-selling tools (from a time when people made their livelihoods from them) are often an indication that they aren't useful tools.

The boundaries between the four approaches I list above ought to be porous, not impenetrable. In other words, one shouldn't only stick to buying from Big Box or from boutique vendors. In the first example, you know you're going to be buying cheap import stuff. In the other, you're often going to be paying a premium, or buying quality you don't need.

And yet, once you start acquiring hand-powered tools, you'll probably find yourself tending mostly toward one approach or another, using the others only when your preferred method isn't an option. Using myself as an example, I tend to hover mostly around Approach No. 1, and my most productive hunting has been at antique shops.

Antique/Yard Sale/Flea Market/eBay/etc.

The antique shops I go to tend to look more like well-curated rummage sales than the sort of places one would normally associate with "antiques." I refer here to the establishments run by a prim lady dressed like a Public Television "Leader Circle" donor, and that carries nothing costing under a thousand dollars.

I don't go to those sorts of antique shops. They have nothing for me.

The "well-curated rummage sales" are where they keep the old tools. I like antique shops because unlike eBay, I can handle the tools and see whether they're good or poor. And while the prices are higher than yard sales, the chances are good I'll find something useful - dealers paying for space at an "antique mall" don't usually put out rusted junk that won't sell. The big one in Michigan City is where I found my No. 5 jack plane, pictured disassembled here:

I dished out a cheap sharpening stone dressing this plane's iron

It's not a collector's item. I think I paid $45 for it. It complements the No. 4 bench plane and the Stanley spokeshave I've had for years, which were also bought at an antique store.

There's an antique place in LaPorte where I've found lots of good tools. One of my favorite finds there was a "breast drill" that I've used everywhere from Chez GVI to my Reserve Center (drilling pilot holes for a mounting bracket for gas mask bags) to my day-job, using a concrete bit to drill property-corner monument holes in sidewalks in Chicago.

As much drill as I've ever needed

I think I picked up my brace at the same shop at the same time. It's unremarkable - if you've seen one you've seen 'em all. The auger bits for it are a different matter. I've never had a full set - just odds-and-ends and crummy ones at that. A couple weekends ago, however, I visited the LaPorte antique place and there was a cardboard box full of good bits of all kinds. It had not been set out yet but the booth owner was there and took $25.00 for the entire box.

This is what $25.00 will get you in LaPorte, Indiana

You can see which bits I was interested in by the fact they have corks on their screw-tips. Provided you can find these things new (no one is making them with square tangs like that anymore), they tend to go for upwards of $100 just for that set with the corks! You can also see that in addition, I have several replacements for the commonly-used ones, as well as a large set of machinist's bits.

Between antique places and eBay, I've got a fair collection of saws, as well as a few "specialty" hand planes.

There's a hint in this picture...

The photo above points to one of the disadvantages of antique tools. Most tools you find this way will be good quality but, as a rule, they will all need cleaning up and de-rusting, and some may need outright repair. If you don't enjoy restoring hand tools as much as you enjoy using them, you'll either become VERY choosy about what sort of antiques you buy or may even discard them as an option altogether.

Take a look at the planes above. They all needed servicing. Their irons needed to have the rust ground out and their edges re-profiled, the wood needed finishing, and everything needed to be cleaned. Some were cheap because they're incomplete. The skew rabbet plane has a broken wedge - it'll work but it's also a hassle. I'll need to make a new wedge soon. The complicated plow-plane was likewise cheap, because it was missing all its irons as well as its wedge. I can make the wedge, but had to order a set of irons (8 is considered a full set) from eBay.

Big Box/Amazon

Looking at what I just wrote, you might get the impression that I'm looking down my nose at the Big Box Hardware stores and at Amazon. That would be oversimplifying. It's true that Big Box stores and Amazon sell things cheap; but not everything they sell is useless crap either.

Take a look at the clamps in these photos:

This is part of a workbench I'm making at the time of writing.

How are clamps like Coca-Cola?

These clamps are a lot like what Andy Warhol said about Coca-Cola:

"What's great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it."

A wood screw clamp costing twice what I paid for those two isn't going to hold the work twice as well, so there's no point in spending more. Similarly, in my Amazon cart right now there is a set of Japanese "cuts-on-the-pull-stroke" saws like those seen in the Japanese woodworking photo above. I haven't pulled the trigger on them yet and I've never used Japanese saws, but I'm told by those who have used them that they're VERY good, and they're much cheaper than a Western saw of the same quality.

Cost does not always equal value.

There's another angle to Big Box and Amazon, which is part of a larger debate one Rubie summed up as follows: "New people will ask, 'Is this Harbor Freight lathe okay for starters?' We end up with most saying, no. Then a few chime in--but he won't get started if he doesn't have the money to do so. Then we have the back-and-forth on safety, how much you should be willing to compromise, etc."

You go to that Rex Kruger video I shared earlier and wander around his channel, you'll find him monkeying around with a LOT of cheap, disposable tools, while at the same time sharing his appreciation for the indestructible ones, and hinting strongly at their advisability.

I can respect his approach. To the degree I understand it (and I think I do), it's "What do we need to get started building NOW?" He values skills more than stuff.

It's not the master/apprentice approach of spending seven years of cleaning up the shop floor before you're even allowed to touch a tool. I just got this book and in it, the author talks about tools his master would never let him touch. I find such an approach somewhat offensive for several reasons, none of which need to be gone into.

Kruger's approach is different. "Get started building and if it takes cheap tools to do this, here are the cheap tools I've found that get results." This isn't (quite) my approach either, except in the department of chisels.

The chisels in this tool roll are cheap Harbor Freight crap

I paid $12.00 for these, while waiting for a set of Narex chisels I paid over $130 for which haven't yet shown up. I fully expect to trash out these cheap chisels I got, while trying to learn good woodworking habits and the right way to use them. I've long embraced "investing in failure" and "failing forward,' and I don't have to have a conscience about trashing $12.00 chisels. I've already spent a LONG time truing up and sharpening them, and I've even begun to use them. By the time the good chisels arrive, I will have made many of the mistakes learned many of the lessons I need to in order to get the most out of the expensive ones.

The reason the debate is set out the way my Rubie friend said is because it's not the debate woodworkers would be having a few generations ago. That discussion would look more like: "Should I let my apprentice learn with my 'paying' tools or should I start him off with my castoff junk?"

Breakfast-powered woodworking tools were made the way they were Back-In-The-Day because people made a living with them. Folks still do, but as a "cottage industry" and not as an actual "industry." And hobbyists/homeowners aside, the way a person became a master woodworker was because that's what he got paid to do, and his tools reflected his profession - anything from "apprenticeship-and-acquiring-good-tools-over-time" to "Signing things out from the shop tool-room."

Nowadays, the relationship of craft woodworking to industry is inverted. The vast majority of people get their furniture the same place they get everything else - The Store. And The Store gets their furniture from factories.

So my Rubie friend's debate among her peers is a valid one, because the "old way" of answering the question is related to a context that no longer exists and hasn't since the mid-1800s.

For my part, I still prefer the antique hunt; and yet, I respect the cheap-but-fit approach too.

Small-Scale Craft Vendors

Next on the list of approaches is buying from small-scale craft vendors. These are outfits like Lie-Nielsen, Lee Valley Tools and Veritas, who are putting out tools of similar quality to those made when people made their living with them. They are expensive; but it's worth realizing that they're comparably priced when adjusted for inflation. In other words, they cost as much in today's money as they cost Way-Back-When, in Way-Back-When's money.

One of the two principal influences in my recent woodworking has been Rex Kruger, whom I've mentioned already. The other is a guy named Christopher Schwarz, who is a woodworker-for-hire as well as an author and teacher. Look at the photos of the tools in his "Anarchist" series of woodworking books (the tool list starting on Page 29 of his Anarchist's Tool Chest is the only such list a new woodworker needs, and the book is worth every penny spent on it); and if they're new, they're in this class of quality.

A fellow with his passion for woodworking, who's also making his livelihood with hand-tools and teaching their use, has a reason to buy tools that good. I, on the other hand, am what my friend calls a "hobbyist casual." I usually don't need that sort of quality. It's even harder to make a case for it in a pure preparedness context.

And yet, I won't dismiss the approach wholesale. I'll note one exception in my own case, just to show it exists and why. Remember that workbench I said I'm making? It makes use of a gizmo called a "holdfast" to clamp down work in the middle of the bench. A holdfast is an iron rod with a sort of "finger" extending from it, which is set into a hole in the bench, the finger pressing down on the work. It's held in place with a tap of a mallet.

Simple and efficient

You can find holdfasts for dirt-cheap on Amazon; however, their reviews are largely awful. Most woodworkers who suggest an alternative suggest a company called Gramercy Tools, and the reviews for their product are universally favorable. Their holdfasts are about twice the cost of Amazon's, but guess whose holdfasts I'm putting on this workbench?

Roll Your Own - Making Your Own Tools

To one accustomed to getting everything he needs from The Store (whether "The Store" is a Big Box, a website or a guy's garage), the idea of making one's own tools sounds preposterous - the realm of rednecks, and not the clever kind. It's certainly hard to make a preparedness case for it, particularly to one who isn't interested in getting really good at woodworking but is only interested in repair/reconstruction.

And yet, a preparedness case can be made, albeit indirectly. It is this: Making tools teaches the skills of woodworking and confers the confidence of tool-making.

If I can make a mallet whose head doesn't crush to mush and stays on its handle, I've demonstrated mortising, sawing, chiseling, knowledge of the properties of woods and more. If I can make a wooden straight-edge that's perfectly straight, I've demonstrated my competence with planes and can use them with confidence. If I can make a try-square that's actually square, I've demonstrated my competence with not only planing but also with dovetail saws, drills, simple joinery and more. If I can make a dowel plate, I've demonstrated competence with machining.

What's more, knowing that we can make our own tools gives us the confidence that, if we need something we don't have, we can just make it, while one who lacks any such skill is at the mercy of Fate. That confidence goes a long way.

These are intangible preps, these "competencies." But competence and confidence are indispensable in a catastrophe, and the most important preps are mental. Saying "I can do it" and knowing "I can do it" are powerful "force multipliers" - often, this attitude alone is what separates those who survive a catastrophe from those who don't.

Some time ago I wrote an article on the desirability of knowing how to do important things three ways: High Tech, Low Tech and No Tech. Working with hand tools falls into the "Low Tech" approach - a space between the modern furniture factory or construction site on the one hand, and the straw-hut, loincloth bushman on the other. The approach I've laid out for woodworking tools and their acquisition applies equally well to other prep items; but more than simply acquiring tools, the prepper ought to give an eye to the skills he or she is laying hold of as well, and also the possibilities that such tools and skills, used together, open up for him or her.

"But now, perhaps just because peace is not going according to plan, certainly not in the way that we, the ordinary citizens, had imagined it, there are opportunities which will give us the thrill of vital living if we care to seize them, the difference being that these opportunities do not come unsought.

We have to find them."

- The Woodworker,

December 1947

"With industry there is no coping. More and more it is establishing its own claims, which we are forced to recognize.

But men who have fighting souls will keep intact their freedom to do and be, and there is no better way than the craftsman's for safeguarding those things."

- ibid,

January 1962

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2023 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.