Don Diego: "Do you know how to use that?"

Alejandro: "Yes - the pointy end goes in the other man."

*Sword-fighting For Fun and Profit*

This is Part II of a series; Part 1 is at "Swords - Why Not, And Also Why"

Don Diego: "Do you know how to use that?"

Alejandro: "Yes - the pointy end goes in the other man."

If anyone were interested enough to undertake the search, there's no doubt in my mind that somewhere, someone has written a doctoral thesis on why people are so easily mesmerized by swords, as opposed to other "sweat-propelled" weapons like spears, poleaxes and war hammers.

Sir Richard Burton (translator of "A Thousand Nights and a Night" in 1885) tried to explain it in his 1884 volume "The Book of the Sword," but all he really ended up doing was projecting his pompous Victorian Limey inclinations onto the weapon. Many centuries previous, Fiore dei Liberi said about the same thing only in Italian, in his 1400s manuscript Fior di Battaglia ("Flower of Battle"):

"I am the Sword... And I am Royal and I maintain the justice; I increase goodness and I destroy malice...."

Which is more or less the same as Burton wrote, only much more concisely. Look throughout the writing of most cultures of long-standing and you'll find they impute their swords with equally noble virtues, conveniently forgetting how swords were the arm of tyrants as well. Everyone wants to feel good about themselves; and remember, the people writing these sorts of things about swords are doing so from the perspective of a society with an aristocrat or noble class (in which the sword and its use is largely the province of the nobility), and an understanding of "class" or "caste" itself which is not only entirely unknown to Americans, but essentially impossible for us to conceive. This fundamental distinction goes a long way to explaining why America has never had a "sword culture," nor anything resembling one.

Yet it's no exaggeration to say that swords enrapture people the world over in a manner which is outwardly similar to the hypnosis a cobra has on its prey. Most people who see a sword - or even a ridiculous facsimile of a sword - find it hard to resist the temptation to hold it, if there is the least chance of them being allowed to do so. Get two people with real or phony swords at the same time and it's the rare saint who can refrain from pantomiming a sword fight with them - often with results which are comic or disastrous or both. Even a reasonably well-trained swordsman can hardly overcome the impulse to take hold of a sword and at the very least get a feel for its balance, even if he can restrain himself from juvenile stage-play.

Many cultures have dances featuring swords. The Cossacks and Scots are the most familiar, and belly-dancers with swords balanced on their midriffs or heads (!) add a level of irresistible allure, even though everyone knows it's a specially made stage prop.

This essay will not attempt to answer the question of peoples' fascination with swords. The author is no psychologist - we simply accept the condition as given and universally observed. Neither will it attempt to give any good reasons for learning swordsmanship. You will either think it's cool and fun, or silly and hazardous, and you will think this at a level in your brain which is unreachable by reasoned discourse. People's feelings toward swords, one way or the other, are ALWAYS visceral, never cool and detached.

We will, withal, lay out the practical aspect of going about learning, with links and resources for the interested novice to learn further.

For the idle curious, (l-r): U.S. 1850 Staff & Field Officer's Sabre, cheap knock-off Chinese "dadao," Chinese "jian" straight sword and "Tai chi" style "dao" sabre.

My 1840 NCO sword is not pictured - it's for display only.

In Part I of this series, I said I train in and teach sword arts and use a machete at work. For this part, the reader deserves to know a bit more about my curriculum vitae, so he or she has the faith that I know what the heck I'm talking about.

At the time of writing, I "co-train" in British military sabre with a Lodge Brother. In addition, I know Chinese swordsmanship to a reasonable degree of competency through learning and teaching Yang style tai chi chuan, which has "forms" for their straight "jian" (looks a bit like a medieval arming sword) and their curved "dao" sabre. In addition, I know the very basics of Indian swordsmanship with the tulwar which, combined with their "dhal" buckler, had a well-earned reputation for being a highly respected and formidable close-quarter weapon, when properly used.

Lastly, I train somewhat haphazardly with a cheap copy of a Chinese "dadao" and combine the simple methods taught for it with those parts of Italian longsword which can apply to both and enhance the former. This might seem mismatched, ill-advised and (to certain history buffs) even a bit disrespectful. I feel justified in this corruption of historical methods for the following reasons:

The desire to learn European swordsmanship grew out of my daughter presenting me with a Model 1840 NCO Sword on my retirement from the Army. I reckoned if I have the thing, I may as well have some idea how to use it.

I chose the British method based on the following:

(l-r) Baseball bat, "jian" waster, "singlestick," "gymnasium" sparring sabre.

Indian "dhal" buckler behind trainers.

(dao trainer not shown - it's at the school where I teach)

I made some singlesticks, which are the historically appropriate trainers for British sabre, and would work equally well in training Highland broadsword or the more nimble smallsword or "spadroon," of which the 1840 NCO Sword is an example.

Step 1: Down the Rabbit Hole

Everything that follows is informed by what sort of sword one has or wants to own. You may have no prior experience and no sword, or you may have an historical example passed down through the family or (as in my case) presented as a gift.

If you have no sword, there are plenty of places to get good ones; but like everything, there is a certain price point below which you're looking at something fit only for display (picture in your mind's eye what my friend calls "gas-station katanas" and you'll be in the ballpark). Of the many vendors, I can endorse "Kult Of Athena" (link below), as I've done business with them. They have no showroom, but they are knowledgeable and helpful, though they rightly expect you to know what you're talking about and what you're asking.

Browse around the site and see what interests you. I can't help much here, except to say it pays, once you've settled on a sword you like, to watch a few videos of people talking about the sword and, more importantly, realistically working with it - we'll touch on "stage swordsmanship" later.

For example, I might say, "Ooh, this Swiss Zweihander looks AWESOME!" and spend a week's pay on it before I realize I need to grow six inches taller and be as fit as an Olympic gymnast in order to use it properly.

Or I might find:

You get the picture. Do some homework.

Step 2: You Mean That's Not It?!

So you've found a sword you like, it fits your budget, and its style seems like something within or very near your current or projected capabilities. There are a few more things you will want to consider before you take the plunge, and the first of these is a training sword, often called a "waster."

Training - to say nothing of sparring - with a sharpened metal sword is irresponsible. Self-evident safety issues aside, you're going to put your very expensive sword through unnecessary wear-and-tear. Occasional "test cutting" is valuable, but if you're at the I-Still-Don't-Know-What-I'm-Doing phase, this must wait.

Wasters are made for most styles of sword, and there's a link at the bottom for a company who sells good ones at reasonable prices. But there are exceptions, and my "dadao" is one such. The company I linked to will sell me a synthetic waster, but I don't much care for its looks. Another, smaller company will gladly sell me a very nice two-toned wood one, but it costs nearly twice what I paid for the sword itself. In the end, I just train with a baseball bat that's within an inch of length and "point of balance" and within a few ounces of weight.

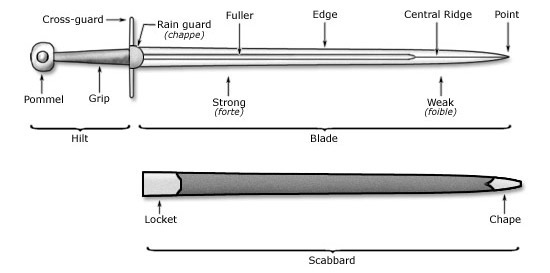

Now that I mention point of balance, I ought to spend a few minutes discussing it and a few more concepts related to swords and their properties. Note the following image:

Most swords have these parts and most of them are self-explanatory. The grips may be different; there may be "false edges" as on the back of a single-edge sabre, and the cross-section of the blade may cause it not to have a "central ridge." There may be distinct design features like the "yelman" on Turkic and some Asiatic swords (the "yelman" is the part that makes a Shriner's scimitar look the way it does). On some examples, the quillons may be in the form of an elaborate guard or, in the case of the Russian/Cossack "shashka," there may be no guard at all.

A few of the parts require more elaboration. "Strong" and "weak" (or "forte" and "foible") don't refer to the relative strength of the blade. They refer to positions on the blade where guards and parries are supposed to happen. If an opponent attempts to deliver a cut on me, I will try to deflect it by meeting the back half ("Strong" or "forte") of my blade with the front half ("foible" or "weak") of his, in order to have greater mechanical advantage over him. In this way a small person like me can fend off the blows of a much larger and stronger opponent, but this only goes so far (picture Frodo vs. Conan).

Two parts of the blade are not pointed out, and those are the "point of balance" and the "center of percussion" or "sweet spot," to borrow a baseball term.

The point of balance is exactly that - the point on the blade where the whole thing will balance if placed there. Take two swords of identical design and equal weight: one whose point of balance is closer to the hilt will feel "lighter" or more nimble, but harder to control, whereas the one with a point of balance "well forward" will feel heavier and will hit harder, but require more strength to use swiftly.

The center of percussion is a location on the blade, several inches back of the point, where all of the energy delivered into a cut will be transferred into the target. It's exactly the same thing as the "sweet spot" on a baseball bat, and is considered important to know for the same reason. This term is relevant to swords which are designed to have some cutting ability - thrust-only swords like smallswords, foils, estocs and most rapiers make no meaningful use of the center of percussion.

Eventually, you will want sparring gear but that's not terribly important just yet.

Step 3: R.T.F.M!

One of the most important reasons certain forms of swordsmanship are more popular than others is because the records of their use have survived. At an extremely simplistic level, all swords are used in more-or-less the same way - they're all sharpened bits of metal and they all cut and/or thrust ultimately into and/or through flesh and bone. The differences in style come about

...and so on.

In practical terms, it's not really so that if you know how to use one type of sword, you know 'em all. I know how to use the ones I outlined in the introduction, but I can't say I can use a Japanese katana, or a rapier or an arming sword/buckler. If I tried to use the katana - a two-handed sword - the same way I use my dadao (also two hands), I'd very likely overswing on cuts, or break the katana by trying to parry a blow in a way it was never made for. If I tried to use the rapier like a sabre (because they're both long one-handed swords), I'd spend a great deal of time painfully but harmlessly smacking my opponent, and getting my point turned aside because of the difference in balance. If I tried to use an arming sword like a jian (because they kind of look alike), I'd probably break my wrist because of the profound difference in balance.

So go back to the videos you enjoyed best about realistic sword use and find out where the swordsmen learned what they did. You'll find they learned their art one of two ways:

Sword methods usually developed because they worked - there's no point, all these years later, to try to make the wheel any rounder. In the case of methods that didn't work, they either didn't survive (just like their users), or else in the case of the Chinese dadao, it was the best they could come up with, and the survivors prevailed in different ways.

Asian cultures have several "living" traditions, with lineages going back to their founders; although despite what you may believe, most of their fencing methods are nowhere near as old as the earliest European methods on record. The oldest Asian arts for which we have any record or lineage date from no earlier than the 1700s, whereas Fiore dei Liberi's manuscript was written sometime around 1400, and it's far from the oldest.

So find what you can on video and in print and spend some time studying it, even before your sword arrives. Most of the old stuff is online and I'll provide a link for an online library of "Historical European Martial Arts" (HEMA) texts below.

Step 4: Sweat Equity

While waiting for all your "implements of destruction" to arrive and concurrent with your scholarly research, start to condition yourself for your new activity. An exhaustive conditioning regimen is beyond the scope of this essay, but you could do much worse than the following exercises in order to get yourself ready for learning whichever style you're keen on:

All these will relate to the work of learning most styles of swordsmanship - and if it looks like most of the exercises are for the parts of the body that should never touch or be touched by a sword, YOU'RE EXACTLY RIGHT! Lower body and core strength are under-sold in sword arts. While I can't give authoritative reasons why, I suspect part of the reason has to do with modern man being far more sedentary than his ancestors - they just walked a heck of a lot more and didn't need the conditioning like we do.

Step 5: IT'S ALL HERE...Now what?!

The Big Brown Truck just dropped off your "bundle of joy" and you're eager to get started. If you have the benefit of a club or school nearby, take full advantage of it. The money and time you spend there will return results much quicker than anything you attempt all-by-your-lonesome. If, however, you are forced to be all-by-your-lonesome, there is a fair bit you can do before you run into the "partner wall," which I'll discuss shortly.

Asian martial arts are generally taught in the pattern of "forms" or "kata," which are choreographed "dances" if you will, meant to instruct all the necessary moves in the art - offensive and defensive - from start to finish. Generally speaking, they are assembled more with a view to flowing smoothly from one move to the next, rather than one move logically following another as it might in combat. Partner work is typically taught after one has mastered the form; first with choreographed "plays," and then finally open sparring. It is generally easier, compared to European arts, to learn the forms or "kata" on one's own (without a training partner), though bad habits will unavoidably creep in if not corrected by an instructor.

Most Asian weapon trainers insist upon the student learning the empty-hand form of the broader style first, for good reasons having nothing to do with making the student pay for extra lessons. Asian martial arts tend to differ from European in that the weapon techniques derive directly from those learned empty-handed. In other words, in learning to fight empty-handed, the student also learns the fundamentals of the sword portion. It takes less time to train the small but important details that make for a good swordsman, and he thereby has two complementary and effective fighting systems at his disposal.

European martial arts, by contrast, are generally broken down into sets of skills to learn - all cuts, all thrusts, all guards, parries, combinations, feints etc - and then worked together in solo or partner drills which are progressively expanded. The student is then expected to integrate these drills and what they contain in open sparring. They don't typically require knowledge of an empty-hand style because the skill sets are all trained separately and no attempt was ever made at making them correspond.

In other words, if you want to learn boxing, you learn boxing; if you want to learn swords, you learn swords - they usually aren't complementary in the same way Asian arts are. For example, there's grappling and striking all throughout Fior di Battaglia, but the "shoulder dislocating" techniques don't teach you anything about sword use.

From the videos and the texts you've assembled, it should now be possible to begin to learn the basic cuts and guards meant for the sword you own. You should be doing them with your waster until you reach a level of confidence that you can be safe around others.

This is counterintuitive, of course. You may hear some Viking-helmed ancestor shouting mockingly at me from Valhalla, "FOOL! IS NOT SAFE! IS WEAPON!"

Well, yes and no, and tell Fjorghtnyur the Dyspeptic to go back to his Mead-Hall-In-The-Sky...

Your weapon is intended - as all weapons are - to cause anyone at the opposite end of it to have a Horrible-Awful-No-Good-Very-Bad-Day. On the other hand, who exactly gets to have that Horrible-Awful-No-Good-Very-Bad-Day ought to be entirely under your control. It's a sword, not a land mine.

Try this experiment. Using your waster, go into your backyard or wherever else you have a large area free of obstruction; once you make sure it's clear of family, friends, pets and people who owe YOU money, make the most powerful cut, thrust or parry you can. At the apex of your swing, cut or thrust - let go. See where it landed? Pace off this distance. From the moment you pick up your sword "for reals," the distance you paced is the distance no one you care about should be without sparring equipment on.

Some swords - German & Italian longswords and 19th century sabres are examples I'm aware of - come in blunt-and-dull steel for more realistic training. They're not stage props (about which more later) but steel swords expressly made for sparring with equipment on. German longsword trainers are called "Federschwerten" or "Feders," and sabre trainers are generally called "gymnasium" sabres. They are thin steel, with more spring to them, and as a rule they weigh slightly less than a "combat-ready" example would. They're no substitute for a waster, but they are an option for some types of sword.

I bring them up because we're not quite done with solo training. From time immemorial, students of swordsmanship have trained against a wooden post known in English as a "pell." The pell is any wooden post, solidly set in the ground or with a very heavy base. They are as simple as this, or one can add targets in the form of tires or basketballs or anything the imagination conjures.

My property is not huge and there are no fences to keep off the idle curious, so if I want to work on aspects of swordsmanship AND have a modicum of privacy, it must be done indoors. For this, I've made what's known as a "pendulum pell" in English; but since it's mine and I can call it whatever I want to, I call it by its German name of "Pendelziel" which means exactly the same thing. It's a cheap, homemade version of a brass Pendelziel mentioned in a fencing treatise by some German guy in the 1500s. Purpleheart Armoury mentioned earlier will sell you a VERY nice one for $140.00. While I can afford it, I also have better things to spend $140.00 on.

Its construction is so straightforward I really don't have to describe it - just have a look:

I've pulled the cord up into the "Kong" toy so the snap swivel is inside, but otherwise what you see is what you get. It is a challenge hitting the ring when "giving point," but it's not supposed to be easy.

Step 5: The "Partner Wall" and How to Overcome It

Unless you're a misanthropic hermit, you'll eventually tire of just practicing dry drills and whacking a fence post. What's more, no fence post or pendulum will ever teach you proper parries - these can only be learned by interacting with another fencer.

This second part is important. Part I of this series was inspired by a discussion on a board connected with bushcraft, wherein one of the members introduced a nasty little short-sword/machete that was intended primarily as a weapon more than an agricultural tool. The video accompanying it showed its maker or his trusted friend taking swipes at all sorts of targets and made it look like just the thing to have for the zombie apocalypse. In fact, this is exactly what the maker had in mind - he says the following: "it's for people to have hanging around in the event of civil unrest for cases when you want to arm your friends/family, but don't want to just hand out firearms to untrained people."

Swords are the hardest of all muscle-powered weapons to learn, usually in terms of months or years; and yet, anyone can learn the basic cuts of any sword system in less than a half-hour's time. The remainder of the time is spent learning not to get killed. It took a lot of patient explaining to the fellow who presented the weapon above that teaching someone to hack and stab without teaching them to parry and guard is essentially teaching them how to die gloriously (the military history of the dadao demonstrates this with gruesome clarity); that it takes far less time to teach people to shoot safely than to use a sword without getting themselves killed (or hacking their buddies), and that if we're talking "friends/family," there's no such thing as an acceptable level of casualties.

Millennia of experience have proved it's impossible to learn to defend unless you have someone to defend against, and this argues convincingly for finding a training partner.

I can't give definitive advice on finding sparring partners - there's no Bat Signal for swordsmen - but a few suggestions wouldn't be out of place:

Be advised, if you decide to attend a club or school, you will be exposed to people who are at your level of competence, as well as above & below it. You're probably not going to be the smartest person in the room - be open to suggestions and prepared to unlearn bad habits. They'll have their own safety rules - abide by them. The club members will be people from all different walks of life - it's a great opportunity to learn about the type of people who share your interest...and absolutely nothing else.

Lastly, show up somewhat refreshed and not at the end of your tether. One of the most surprising things I ever learned about fencing is how mentally exhausting it is, in addition to the physical exertion. Sparring with another person who is trying to hit you, while also trying to prevent you from hitting him or her (LOTS of women in HEMA and they're good fighters) is one of the most challenging puzzles on earth. Imagine being Singer Rainsford from "The Most Dangerous Game," running from General Zaroff's dogs, while trying to work a Sudoku puzzle.

Once you reach this level, there's nothing more I can advise, as there will be others to guide you.

LINKS:

I'd be remiss if I didn't give credit to a Rubie who's contributed more to swordsmanship worldwide than anyone else I know. That would be our own SGT Blade, who makes swords I can't hope to afford, ships them worldwide, and is an accomplished swordsman and historian in his own right.

APPENDIX: STAGE SWORDSMANSHIP, or WHY DON'T I LOOK AS COOL AS I FEEL?

I promised I'd get around to discussing stage swordsmanship - the sword fighting you see in plays and movies. There's an excellent exposition of the topic here, but it's quite long - I intend merely to give the "tl;dr" version.

Watch enough youtube videos of actual swordsmanship and one of the first things you'll notice is that it looks a lot more like a knife fight than a sword fight. Rather, it might be better to say it looks more like how a knife fight looks than how we think a sword fight should look.

If you're anything like me, you grew up on a steady movie diet of Tyrone Power, Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone running each other through in castles, on the decks of ships and so forth. As we grew older, we watched lightsaber duels, Antonio Banderas as Zorro and now most recently the fantasy swordplay in "Lord of the Rings" and "Game of Thrones." These are all great fun and the best of these sword fights are a thrill to watch, even for one who knows what's going on. I'm a big fan of Chinese wuxia movies, and I always enjoy the duel between Michelle Yeoh and Ziyi Zhang in "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon."

Sword fights in movies look like they do for several reasons. First is the tension between having two people look like they're trying to kill each other, while simultaneously ensuring that no one in fact does so (actors are expensive). They also take a lot longer - about 3 or 4 minutes on average - than a sword fight, which in "the real world" seldom lasts more than ten seconds.

This is because the fight is a "story within the story," full of drama, tension and action. You can't just have the hero parry the Big Bad and run him through in the blink of an eye - who wants to watch that? Even the ones where the fight is over in a single blow - the duel in "The Seven Samurai" is a good example - they take a minute-and-a-half to actually get around to the fatal strike.

Conversely, in real sword combat, the two antagonists are trying to land a telling blow as quickly as possible, and it's not pretty. If you do a youtube search for "1967 Epee Duel Deffere vs. Ribiere," you'll see the last duel in France, filmed as it happened. It's rather boring and anticlimactic (both combatants survived - only one was slightly wounded) and the entire "fight" only lasted about 20 seconds, all added up.

In poorly-filmed sword fights it's obvious the actors are too far away to land a blow on each other - the "clang-clang-clang" of back and forth swords-hitting-swords is hard to film well. Good directors will post the cameras so as to focus on one actor or the other, the better to create the illusion that they're closer than they are. In real sword combat, the antagonists move in and out of "measure" (the fencing word for being "in range") until one gains a real advantage and that's just about it.

What's more, most actors are far better actors than they are swordsmen. The second-best lightsaber duel in the Star Wars franchise is in "The Phantom Menace" where Ewan MacGregor and Liam Neeson fight Ray Park (Darth Maul). Watch it now that I've brought it up and it'll be clear how only one of them knows what the heck he's doing. The best such duel in the franchise, in my opinion, is between Rey, Finn and Kylo Ren in "The Force Awakens," where the fight choreographer appears to play up the fact that none of the characters who use a lightsaber is very good at it.

Stage sword fighting is a skill distinct from "combat" sword fighting and there aren't many actors who are any good at either. Tyrone Power and Basil Rathbone were themselves expert fencers AND stage fencers, in addition to being A-list actors. Conversely, Ray Park is a tournament-winning wushu master whose only lines were overdubbed. If you want to see good actors who are also good sword fighters, you mostly have to look to China, and even there, they're not very common.

I spent the extra time on stage sword fighting to reassure you that if you're doing it right, you're NOT gonna look like a movie actor.

gvi

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2020 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.