Sylvester: The Scarlet P-p-pumpernickel! En garde!

Daffy Duck: Riposte!

Sylvester: Café au lait!

Daffy Duck: Champs-Élysées! Ha ha, ya ain't got a chance!

*Swords - Why Not, And Also Why*

By: gvi

March 30, 2019

Update 31 December 2019: Part II has been added at "Sword-fighting For Fun and Profit"

Sylvester: The Scarlet P-p-pumpernickel! En garde!

Daffy Duck: Riposte!

Sylvester: Café au lait!

Daffy Duck: Champs-Élysées! Ha ha, ya ain't got a chance!

People have a tendency to bundle up their identity with their gear, and this is especially so of their weapons. Curse a man's opinions all you please; slander his choice of beer, his politics and his lineage and he will abide your abuse in serene peace. But say just one word against his choice of knife or gun and he will instantly demand satisfaction.

"This is your last chance, sir, to take back what you said about Justin Bieber!"

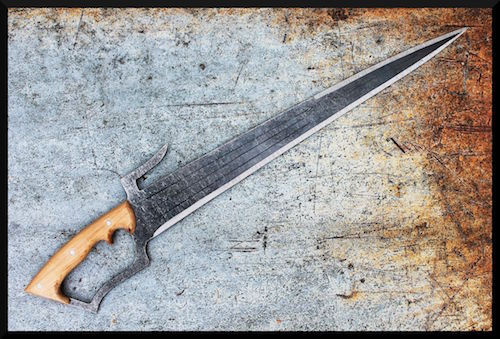

So it was a few weeks ago in a bushcraft forum when I offered my opinion on a savage little implement of mayhem known as a Kingfisher Machete. It is unlike a normal machete in that, instead of being balanced well forward, rounded at the tip and single-edged, it is balanced toward the grip, tapered, angrily pointed, and sports both a false edge and a rather gaudy quillon. You can look it up if you like but here's a picture of the thing.

Looks like what a Klingon might use to prune the weeds

I opined this had less the appearance of a working tool than that of a weapon; moreover, a weapon I had no use for whatever, particularly as (I'm not making this up) at the time of writing it's sold without a sheath or scabbard. This got under the skin of one member of the forum; a "lively" discussion ensued with him as to what it was really for and what the thinking was behind its invention.

Human nature appears to dictate that certain things, no matter how ill-conceived or poorly executed, will have their admirers. This weapon was no exception and in the present example, the person I was engaged with appears to be personally acquainted with its creator. Naturally, telling him his friend's weapon was anything less than the greatest thing since chunky peanut butter was like telling him his kids were stupid and ugly.

Of course he took offense.

According to him - and these are direct quotes lifted off the conversation - the weapon you see above was intended as follows, to wit:

"designed for civil unrest defense. It's designed to be quality enough to be durable in a fight, but inexpensive enough that buying them for your whole crew (whomever you crew are - family, friends, Zombie Defense Squad, etc...) won't break the bank. Most people know how to swing a sword. It doesn't require a lot of training to be able to use effectively."

"It's designed to be an effective, easy to learn/use, handout weapon for friends and family in a SHTF scenario….it's for people to have hanging around in the event of civil unrest for cases when you want to arm your friends/family, but don't want to just [hand] out firearms to untrained people."

"A large machete like blade is frankly stupid simple to learn to use safely and effectively…and more often than not just the presence of a weapon is enough to deter would-be attackers."

Roll a few of these concepts around in your mind for a while. It shouldn't take very long before the questions start adding up.

We could ask a lot more questions I'm sure, but five is plenty for an article.

"Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth."

Before going further, I should point out that I train to use swords and I also teach a couple different styles (British military sabre and Yang style tai chi sabre). I'm no master but I'm pretty good, and I can & have trained students up to my level of expertise. I enjoy it and I can even make a preparedness case for knowing how to use such a weapon, which I'll do at the end of this essay. Bear this in the back of your mind as we proceed.

Answering his questions in order:

Is it really easier to learn to use a sword than a gun?

NO.

If you're reading this and don't know how to use either a gun or a sword, I and just about everyone else who knows either weapon can assure you the firearm is the quicker of the two to master.

Swords are in fact the most difficult of all the hand-powered weapons to learn. A Chinese maxim related to martial arts goes "100 days Staff, 1000 days Spear, 10,000 days Sword."

Guns are easier to learn than any "sweat-powered" weapon. Just about anyone can be taught to safely load, aim, fire and unload a gun in a few hours. In the span of a week's worth of 8-hour days of meaningful training, you can become a crack shot within the limits of the firearm. I'm a member of a group on Facebook whose focus is what we half-jokingly call "applied violence." Firearm instructors, martial arts instructors, weapon designers, writers, various other people connected with these pursuits, etc. About a month ago, one of them posted a video - which I won't link because it's quite gruesome - of two men fighting each other with machetes.

In addition to sword training, I use a machete at work, so I have some idea how they're used as tools. There's a difference between the two applications, and competence in one doesn't automatically translate into competence in the other.

If you want to clear brush with a machete, you'll swing it in a certain way which focuses on delivering power through the precise area you want to cut, without concern for returning to a guard or leaving an opening in the first place. The plant isn't going to try to stab you or cut you, so why should you care? You'll also use the tool so as to economize on exertion, because you may be swinging the thing all day.

By contrast, with a sword (say a sabre for ease of translating the two items), there's less need to accurately place a cut than there is to get a cut in "wherever" on your opponent in the instant an opportunity presents itself, and the smart swordsman will instantly return to a guard after delivering his blow because sword cuts or thrusts are not always immediately disabling.

Intellectually I knew all this, but until my acquaintance posted this video I'd never before seen it so starkly illustrated. The two men were intent on doing violence with their machetes, but their cuts looked like they were swinging at brush rather than a human. They had no sense of measure, no sense of timing, no thought to guards or parries - they simply jumped out of the way if they could - and their cuts, while smooth and efficient for vegetation, were slow and cumbersome for fighting. They were relying on luck and appearing menacing, and showed no real fighting skill, coolness of nerve or self-discipline. In other words, they were enraged workmen, not trained fighters. For those who are curious, both fighters gave each other wounds which in an austere environment would likely be mortal and certainly be crippling. So in this fight, it might be best to say both men lost.

If I don't trust an untrained friend/family member with a gun, why would I trust them with a sword they don't know how to use either?

It takes far less time to train anyone to use a firearm safely and to shoot/move as a cohesive team than it takes to train them to use a sword effectively as part of a team. One of the reasons firearms were universally issued everywhere they were used - even when they were slow to load and inaccurate - was because it took less time to train someone how to use them than it took to use swords/polearms/bows effectively, and they were comparably lethal.

Remember also - when we're talking about using "sweat-powered" weapons in a group, the user must also take care not to cut his comrade. It's much easier to train people to all shoot in the same direction or cover a sector of fire than it is to train them not to hit their buddies in the midst of a confused melee.

Where would I ever be where a sword would be the ideal weapon and a gun would be worse?

From the perspective of practicality (all other things being equal), the only two places I could conceive that meet this condition would be a boat or a zeppelin. Of these two, a shotgun is superior to repel boarders from a boat, and my odds of being in a zeppelin (to say nothing of having to fight in one) are simply not worth discussing. There may be such a scenario which I haven't thought of, but if I have to do that much thinking in order to conjure it up, it's either unrealistic or vanishingly-low-probability.

Add the legal angle and this question changes somewhat. I can't legally carry a pistol in Chicago. But I can make a case for having a machete on my person for work - even in such an urban environment, scrub brush grows thick enough in the alleys that I often legitimately need it to find a property corner (I'm a surveyor by profession). However, I can't make this same case for carrying a machete to, for example, the Art Institute or Orchestra Hall.

Exceptions such as mine merely prove the rule.

Would a sword really scare off an attacker under "civil unrest" conditions?

It might be best to say that presenting any weapon forces an attacker to make a choice. You hope he makes the choice of taking to his heels; but you'd better have something in reply if he makes the choice of closing with and engaging you.

I said swords are the hardest hand-powered weapons to learn, but this is only half-an-answer.

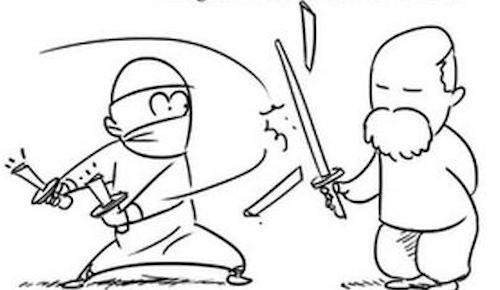

The hard part of swordsmanship isn't "how to swing a sword." Anyone can learn the basic cuts and thrusts of nearly any sword system in 15 minutes to a half-hour (getting good at the cuts of course takes longer but that's another story). So in this sense, my interlocutor was right.

The part that takes a long time - and the part he was obviously not considering - is the NOT-GETTING-KILLED part, and I think we can all agree that unless you're a suicidal fanatic, this is the important part.

It takes time to learn "measure" or how to estimate distances, how to parry, how to recover after delivering a cut or thrust, developing the firmness of nerve necessary to receive an attack and parry it effectively, how to recognize feints or cunningly threaten them, how to deal with different weapons such as bayonets or polearms or chains or baseball bats or tire irons or knives, timing and so forth. These are all the things that take the remaining "9,999 days" of sword training after you learn to cut.

Just teaching someone how to cut without teaching them how to defend is pretty much teaching them how to die gloriously. The Chinese found this out at the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937.

So you're forcing the attacker to make a choice; and if he chooses to press home his attack, you (or whomever you've given one of these weapons) had better have some sort of skill in defense and the spine to withstand the attack.

Hoping to scare the attacker away is a vain hope. Prudent fighters put no trust in the Group Monkey Dance.

What does this guy really know about how to use swords?

Probably about as much as anyone else.

The overwhelming majority of people the world over learned everything they know about swordsmanship from movies. Movie and stage swordsmanship is a specialized, choreographed form of swordplay meant to advance a story while simultaneously keeping the extremely-expensive-and-impossible-to-replace actors relatively safe. Good actors who are also good swordsmen are vanishingly rare. The movies have some very entertaining sword duels - I can think of a half-dozen really good ones off the top of my head.

They also last about three or four minutes.

By contrast, a real sword-fight tends to last only a few seconds before someone gets hit; and except to those in the hobby, they also look kind of boring. This is true of martial arts generally - the flashy fight scenes in a Jackie Chan movie are impossibly long and look nothing like the banal violence of a street corner or back alley.

Try this experiment. Watch these three videos in order. The first is part of the climactic duel from "The Deluge" - one of the "favorite scenes" I mentioned above

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljExTEPNFnMNow, compare and contrast that fight scene with this demonstration of the cutting ability of a modern sword maker's product.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1yoGVv5Vu_ELastly, compare and contrast that ideal cutting demonstration with this matchup between two fighters who have trained in the discipline of using the weapons as they were intended.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgQVtZoM9GII'm sure you've noted the differences in all these videos.

"So you're saying there's no point to learning swords, right?"

Well you never can tell, can you?

Everything I've written thus far points to the futility of swords as weapons. However, I promised I could make a case for learning swordsmanship or some sort of melee weapon, and it's time to keep my word.

First, I should remind the reader of the context of the original set of objections - that giving a short sword to an untrained person and expecting him or her to use it instinctively and well while under stress is foolish. It seems absurd to even have to write it out, and in laying out my argument I've only stated the obvious.

Training, practice and confidence, then, appears to be the difference. Even then, most times a sword is inappropriate. Carrying one around in public is at best freakish, at worst illegal and universally frowned upon. It screams "nerd itching for a fight" and unless you're at a comic book or science fiction/fantasy convention, there's no hope of "blending in."

But the skill is valuable, as is any martial art skill, for the following reasons:

One of my friends takes as comprehensive a view toward fighting arts as possible - everything from systematic situational awareness, to communication skills, to empty-hand and weapon-based martial arts, through shooting skills. Hers is a worthy example to emulate. She takes as her maxim "I want to be the hardest [REDACTED] someone's ever tried to kill."

It's something we all ought to aspire to.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

I'd be remiss if I offered the reader no opportunities to learn more:

There are too many Asian martial arts schools to name, but these systems have sword styles that are for more than show:

www.alpharubicon.com

All materials at this site not otherwise credited are Copyright © 1996 - 2019 Trip Williams. All rights reserved. May be reproduced for personal use only. Use of any material contained herein is subject to stated terms or written permission.